8 Poetry Collections

about Motherhood

Mothers sharing their motherhood journeys through poetry.

by Emma Mott

Motherhood is often a series of impossible balancing acts. It’s impossible to escape the pull between the irritating disagreements and incredible intimacy with your children, the struggle for a sense of self versus the craving to give all you can, the hope of nurturing new life versus the impending doom of . . . well, gestures broadly.

While the topic of “motherhood” is almost as far reaching as life itself, this small sampling of collections is limited to poets who are mothers themselves. These poets find the points of tension and push against them with their pens, letting their readers watch as the words push back. From life to grief to a dystopian octopus-overlord future, these collections span the prenatal years to mothering adults.

Read on to discover more!

Carmen Giménez opens Bring Down the Little Birds daydreaming of finding her mother’s old journal in a closet. The scraps from the journal offer clues to the enigma of her mother. Giménez writes that her mother “was only a mystery when I needed one for the story I made of my life.”

That story is sampled here with Gimenez’s memoir-in-prose at an eventful junction. With a small son, a daughter on the way, and her mother’s memory issues worsening, Giménez acknowledges anything she writes becomes “fraught with motherhood.” In this way, she explores how families write for each other and are written by each other. For Giménez, writing is just another form of knowing, of loving. She writes, “I’ll leave them clues in my poems. My biggest thrill: that they’ll care and read what I write to know me.” After her daughter is born, Giménez writes, “She’s my book.”

A love letter to writing, to her children, and to her mother, Bring Down the Little Birds is a sharp and creative retelling of one of the oldest mystery stories we have: what does it mean to be a mother?

“Some say women forget everything [about childbirth]. I know it’s not true, for I remembered every detail of feeling.”

Toi Derricotte wrote this in an essay about her 1983 prose-poetry classic, Natural Birth. Telling the story of delivering her son in an unwed mother’s home, far from her friends, family and partner, Derricotte’s immersive details proves her claim true.

Derricotte wrote against the societal narrative that birth is something natural, and thus something solely “beautiful and right and good.” Instead, she clings to each moment of her experience birthing her son, delivering a reality: a terrible pain that curls into and explodes across the page. Derricotte uses this striking series to interrogate the way society restricted her, interrogating cultural schemas of sex, womanhood, and relationships.

Natural Birth remains an important story 40 years later, serving to demystify part of the physical sacrifice of motherhood and the mother’s love that arrives.

The first two thirds of Her Birth bends time in and out of a single point: the birth of author Rebecca Goss’s daughter, who passed from severe Ebstein’s Anomaly at less than 16 months old. This is a heartbreaking book. Read it somewhere you can cry.

But do read it. Goss’s simple prose belies fervent emotional complexity. In “St. Mary’s,” the speaker states “People are entering / the church. Her funeral / has started. I cannot stop it.” Juxtaposing warmth with biting loss, Goss offers her readers no respite from the intensity of her grief and shock, down to the miniscule: her daughter’s “teeth that never came” (“My Neighbour’s Himalayan Birch”), “homemade stews / hurled frozen in a bin bag” (“The Highchair”), “a cold pit / of pyjamas” (“Mining”). And yet-

Unthinkably, through the last third, hope and joy rise from the pages. Goss becomes mesmerized by her own life - the joy and grief somehow coexisting. Compulsively readable and endlessly meaningful, Goss’s story is an incredible tale of loss and love.

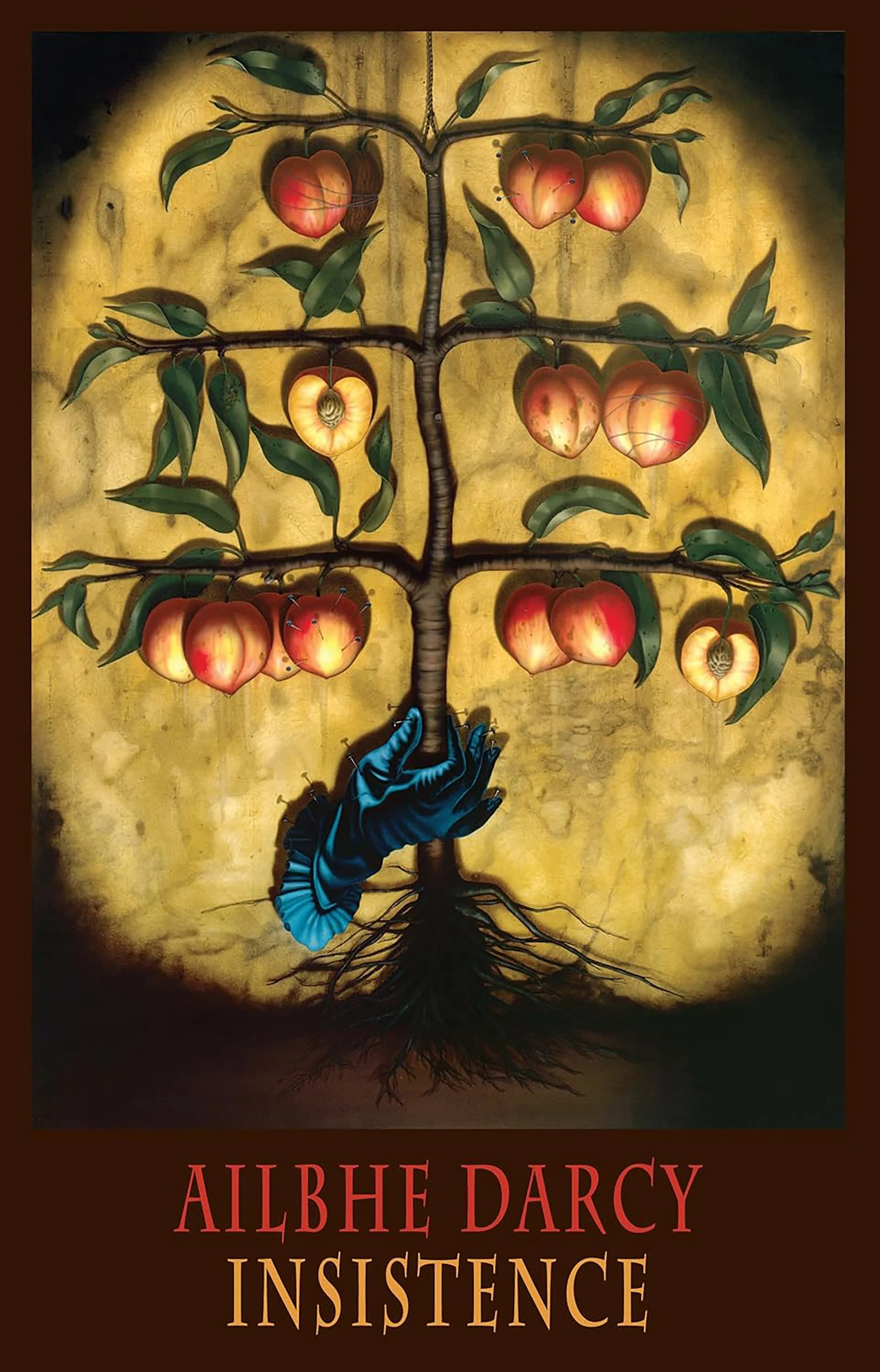

In the opening poem of Ailbhe Darcy’s book, Insistence, the speaker describes the sky to an infant boy as “what it is, taut with its isness.” There is no strict chronological tale here, but a series of soft moments. Set in the American Rust Belt, the book’s central images depict an immigrant family with their young child, watching the sky turn ominous.

Darcy balances a future fraught with darkness with the subtle brilliance of familial love. In “A guided tour of the house and its environs”, she writes, “Nobody needs more zombies Let’s not put zombies in the book.” In their place, the book brims with quiet intimacies: smushing bugs on tile, swimming in the sea, and “lightning bugs just lighting out.”

In this collection, the world shrinks down to the intricacies of Darcy’s Rust Belt family, imagined with stunning images and a sharp musicality. Insistence captures the ‘isness’ of a family and makes that monumental task seem easy.

Rachel Zucker, a mother of three sons, transmits the mundane with a potent pen in Museum of Accidents, presenting her family a bright spark on the humming wire of modern life in New York City.

A poem called “Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday” follows five days: soccer games, poker tournaments, furniture purchases. “Nothing disastrous happened this week,” the speaker reports. “Unless you count what I saw next. . . A teenage boy lying on his side. . . while six or seven other boys ran back and forth and stamped down / hard on his skull.” Relating the events to her husband, the conversation sways into a list of reminders of the week to come, including a doctor’s appointment to reveal whether “these past nine weeks have yielded a fetal heartbeat / which will change everything, nothing.”

Rife with the juxtapositions of mundanity, Zucker’s writing deftly addresses both the ‘everything’ and the ‘nothing’ of the modern world. By the end, you can only assume Zucker created this ode to her family with an electric pen.

Juliet Kono Kono titles her second collection after the experience of the 1946 tsunami that hit her Hawiian homeland. In a PBS interview, she recounts how “the water took the house, and sort of floated it. And we were floating, until we banged into the neighbor’s and a mango tree. . . and the house started breaking apart.” The title represents a series of emotional tsunamis that overtook her life within the span of a few years: caring for a mother-in-law with Alzheimer's Disease, a mother with depression, and an adult son with severe mental illness.

She opens this last section with a sparse, consuming honesty: “My son lives on the streets. / We don’t see each other much. / Like a mother who puts white lilies / on the headstone of a dead child, I put money into his bank account, / clothes into E-Z Access storage and pretend he’s far away— / at a boarding school, or in a foreign country.” It is an impossible situation, so Kono writes as she must: she pens images that state emotional facts. Drawing from her experience as a Buddhist Minister, Kono writes without shame of her son’s life as it was - conspiracy theories, strained sibling relationships, and hospital stints. Tsunami Years stands as a testament for mothers whose children live with addiction or mental illness. Imbued with a mother’s tenderness, Tsunami Years is a stalwart reminder that, regardless of their chosen life path, no child is forgotten by those that love them.

For mothers or anyone experiencing similar situations: the National Alliance on Mental Illness offers family support groups.

Kathryn Nuernberger’s confessional book, The End of Pink, teeters on the edge of twilight - while the subject matter doesn’t seem dark, it is definitely not a light and fluffy read. Nuernberger writes on lovesickness, sex, feminism, and motherhood all through hidden cracks of life most avoid looking at directly: miscarriages, algal blooms, inner-city schools.

As the title suggests, this book examines a loss of innocence. Nuernberger’s language is blunt and specific; each poem forms a door to a different world. For example, in “Testimonial (1888)” - a series of ads for pseudoscience cure-all’s, the poem advertises an “Ocean-weed Heart Remedy ” as the perfect “Blood Purifier” in carefully clipped lines, whereas the very next poem centers on “P. T. Barnum’s Fiji Mermaid Exhibition As I Was Not the Girl I Think I Was”. Here the prose sprawls over the page, highlighting a juxtaposition between the perceived “very ugly and sexually consumptive” “Fiji zombie-mermaids” and the speaker’s narrative of existing as a “flickering and silver-finned virgin.” Early on, in “More Experiments with the Mysterious Properties of Animal Magnetism”, the speaker tells us, “I don’t care to have sex anymore.”Rife with contrast, The End of Pink looks hard at the complexities of identity and motherhood, sans conceit.

While Brenda Shaughnessy’s earlier collection, Our Andromeda, addresses motherhood more directly, the topic still remains centerstage in The Octopus Museum. Well, almost center stage. Perhaps it’s more accurate to describe the cephalopods as gleaming in the spotlight and the human families as more. . . shunted to the wings - but still part of the show! - in Shaughnessy’s fifth book.

The premise: in this post-apocalyptic world, the humans have lost and octopi have risen to power. What remains is the overlords’ display of Life Before: scraps of poems from a wide mix of human voices. Instead of a table of contents, The Octopus Museum has a “Visitor’s Guide.” The premise holds space to interrogate what it means to mother and to love in the face of our great existential threat: climate change. Dedicated to Shaughnessy’s youngest daughter, The Octopus Museum is a truly touching collection.

A must read for mothers who side-eye the news with trepidation or people who just really like octopi - either way, it’s a compelling story.

Emma Mott graduated from the University of South Florida with a degree in creative writing and psychology. After working as an art teacher at the Jacksonville Public Library, Emma moved to Spain, where she now instructs Basque people on best practices for differentiating between alligators and crocodiles in the guise of delivering English lessons. She also reads for the indomitable and relentlessly wonderful force known as ONLY POEMS.