December 18, 2024

AN EXISTENTIAL EXPLORATION

IN THREE PARTS

Book Review: I Have a Bird to Whistle, Buddha’s Not Talking, and My Mother’s Ghost Scrubs the Floors at 2 a.m. by Robert Okaji

by Svetlana Litvinchuk

It can be an illuminating exercise to survey the breadth of a poet’s work to distill something about his greater purpose, to discover what in them drives the often-lifelong urge to write one poem after another. In a close read of three chapbooks by Robert Okaji, it is evident that he is driven by the existential— the hope that peering through the page is a way of piercing the veil to glimpse something absolute about the nature of existence, with poems being the product to show his math while solving life’s greatest puzzle.

In I Have a Bird to Whistle, he employs an unusual form, called the palinode— “a poem in which the poet retracts a view or sentiment expressed in an earlier poem”— as a container for philosophical inquiry. Indeed, poets are known to contain multitudes and reserve the right to contradict ourselves, so it should come as no surprise that this phenomenon warrants its own poetic form. But rather than merely an attempt to correct and revise, Okaji binds a sequence of prose poems with a thread created by using the last line of each poem to spur the beginning of the next one, weaving together subjects that, at first glance, seem wholly unrelated. With this throughline, the poems leap across wide chasms to transport the reader somewhere— perhaps back to the beginning— and in so doing, Okaji essentially answers his own question in the first poem of the collection: “What falters in translation?” leading us to gradually conclude: “Everything falls. Everything. From curve to angle we resist and rejoice” and again in “Plenum”:

A zero’s center defined emptiness, meaning nothing,

Or, diverted light, a vacuum. Regard plenum: an

Air-filled space, or a complete gathering of a

Legislative body. And how did we arrive here

From there?

Okaji’s work is full of these existential breadcrumbs leading us along life’s circuitous journey. The short inquiries-in-verse explore the nature of the human-animal and the animal-animal: what it means to resist versus surrender, what happens with and without input, and how it is the push-pull of the intentional versus the incidental that shapes this experience of being. In his introspective exploration, he shows us it is the journey that matters, a sentiment echoed in the third poem in this series, “(glass)”:

…Once through, what

then? Mention archetype, and my world dims.

Mention windows, and I see processions and

Enemies lined along the way. Boys, please don’t

Block my road. We select certain paths, others

Choose us. Wingprints on glass.

Okaji’s overall writing style can be described as minimalist, sometimes cryptic, and infinitely philosophical. His words are deceptively simple without any splashy displays of emotion. His poems consume little space on the page and his words are chosen with careful economy and precision, but each one is packed with an impressive amount of meaning, giving the 23 pages of his I Have a Bird to Whistle a cosmic density that paradoxically manages to feel light, without overwhelm. For its size, this collection does a lot of heavy lifting by blending cold, hard tools like math and nebulous, mind-bending ones like physics to venture insight into the relationship between nature and spirit.

In the penultimate poem of the series, “(mask),” on the topic of death, Okaji asks: “The paths in our wake delimit the future, but everything falls. Which do we desire more, the grasp or its release?” The answer comes in the following poem: “I release the sun and observe the results.” But for the reader, our urge may be to “grasp” upon reaching the end, experiencing the pull to start over and read it again to discover what may have been missed upon first read.

In Buddha’s Not Talking, Okaji’s sense of humor shines through with his playful amusement at life’s absurdity. Whether he’s pondering the math of incalculable things, writing the most comedic play-by-play of a car accident you’ve ever read, or being brushed off by angels, this book sparkles with lines like “art begins in the heart’s crotch” and “a friend claims love is merely a bad rash,” yet manage to find balance with heartrending lines like “proof that wings claim neither heaven/ nor earth” and “phrases frayed in the mouth and spat on paper.”

In the title poem, Okaji considers a Buddha figurine as he goes about toiling in the garden— a setup for existential inquiry if I’ve ever heard one. His internal narration is as follows:

I fear I’ll never grasp the difference in having and being, that my true

nature has splattered on a trail and the dogs will

sniff it and lift their legs in acknowledgement,

or perhaps acceptance of the infinite, with wisdom

far beyond my reach, before moving on to disquisitions

about soil and fragrance and the need to justify art

with decimal points.

This poignant juxtaposition between the human capacity for abstract thought grappling for meaning in a world of seemingly random artifacts with man’s almost-tame canine companion, who co-evolved to walk the same path while remaining preoccupied with entirely different questions, is a quietly brilliant inquest into the nature of consciousness— his hallmark way of asking what it is we’re all doing here anyway. “Today I’ll sweep, discard papers and/ wonder if I’ll become what I think, whether reincarnation will be cruel or kind. Either way, Buddha’s not talking.” In the following poem, “Threes,” he states,

These thing are not my concern. Not really.

But they arrive in unending repetition, one after the other,

in clumps of three- lovely, lonely triple-threaded lines

of vicissitudes lapping at our ankles, saying nothing,

saying everything, saying it used to be so easy.

This collection bears a curious near-acceptance of the notion that we will never— can never—understand the true meaning of life while we’re still here living it. But, Okaji’s fascination leads him to continue turning it over in his hand like a math problem only to marvel at the infinite number of right answers. “The ruler measures in inches, never minutes, and certainly not in/ emotion.” There’s a message here to all of us and it’s this:

This, to me, is how good relationships

form: explosions of thought and emotion followed by periods

of accretion. But what I mean is I hope this finds you well

by the river of holy sacrament. Remember: brackish water

bisects our worlds. Turn. Filter. Embrace. Gotta run. Bob.

His chapbook, My Mother’s Ghost Scrubs the Floor at 2am, while grounded in the narrative of his mother’s loss, is no less conceptual than his other work.

This collection looks to the natural world as a tangible landscape upon which to process his grief, the work remaining rooted while reaching into the philosophical ether and remaining disembodied as he attempts to grasp at the spiritual—close yet elusive, always just out of reach. In this way, the three collections form a continuum, where a poem from one collection responds to a feeling or impression in another, as illustrated by the poem “Memorial Day,” where he writes,

You looked

like you were reaching for something, she says,

and perhaps I was, though with hand outstretched

I found nothing to hold but the darkness.

His work invites us to grasp at the air with him as we step forward— “because there is no other direction”. Okaji’s uniqueness is his unwavering curiosity about what it means to simply be. But his respect for the reader is always apparent. As with any sage philosopher, he knows we are each responsible for our own enlightenment. It is in this spirit that he gives us a partially drawn map, expecting us to carry the rest of the inquiry forward to work through on our own. To read his work is to walk alongside him in this paradoxically lonely journey, his poetry a beacon, while he asks us to reconcile concepts like: “Stone is constant but harbors no thought to permanence.” In all three of these chapbooks, he is only ever wrong about one thing: when he says, “No one will ever know my poems.” We are infinitely grateful for them and you, Bob.

You can read our 2023 feature on Robert Okaji, complete with poems and interview here.

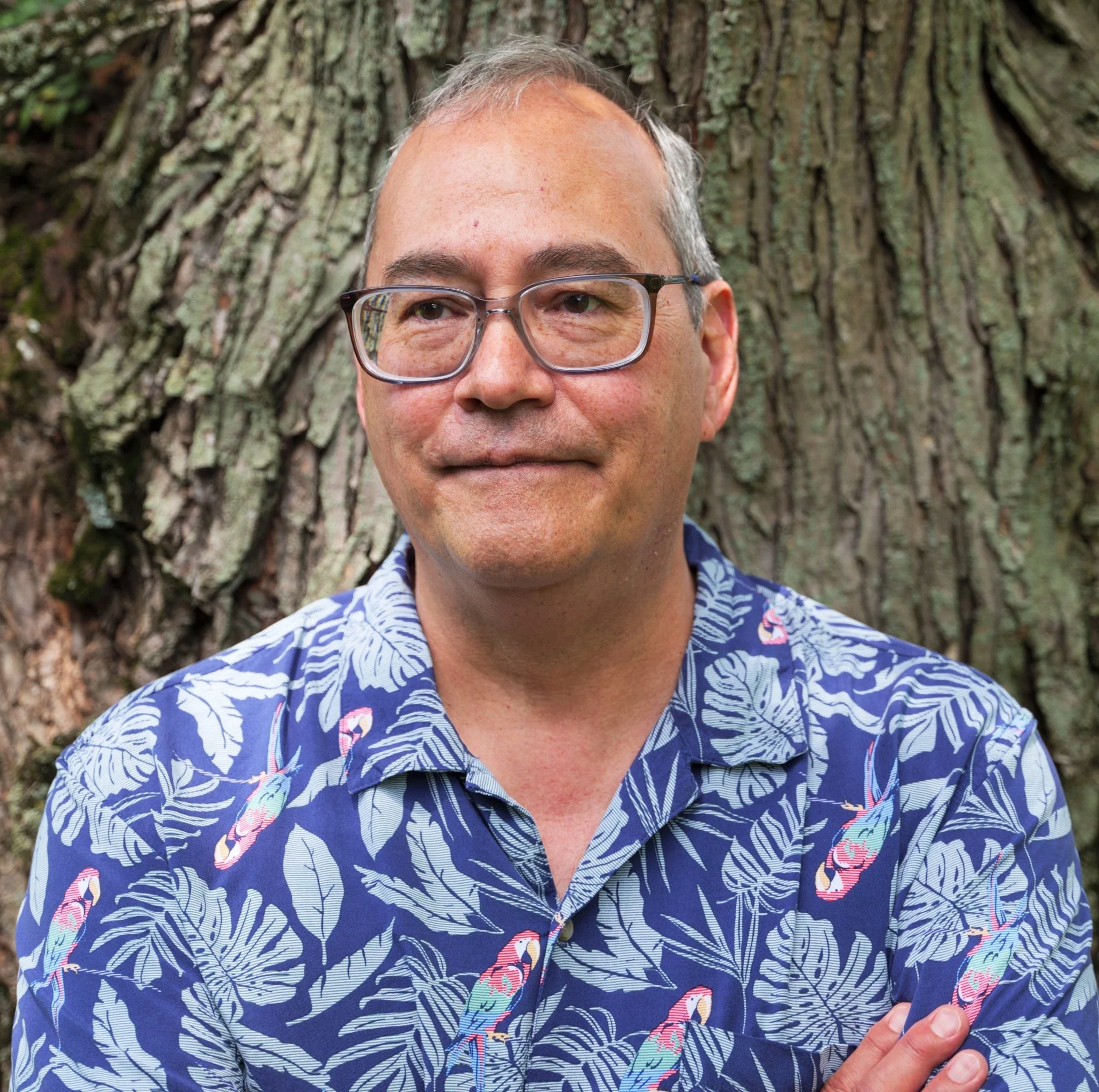

Robert Okaji holds a BA in history, served without distinction in the U.S. Navy, toiled as a university administrator, and no longer owns a bookstore. His honors include the 2022 Slipstream Press Annual Chapbook Prize, the 2021 riverSedge Poetry Prize, the 2021 Etchings Press Poetry Chapbook Prize, and the 1968 Bar-K Ranch Goat-Catching Championship. Nearly two years ago he was diagnosed with late-stage metastatic lung cancer, which he finds terribly annoying. But thanks to the wonders of modern science, he still lives in Indianapolis with his wife—poet Stephanie L. Harper—stepson, cat and dog. His debut full-length collection, Our Loveliest Bruises has just been released by 3: A Taos Press, and his poems may be found in Louisiana Literature, Threepenny Review, Only Poems, Wildness, Vox Populi, Evergreen Review, Boston Review, The Big Windows Review, Shō Poetry Journal, Indianapolis Review, and other venues, including his blog, O at the Edges.