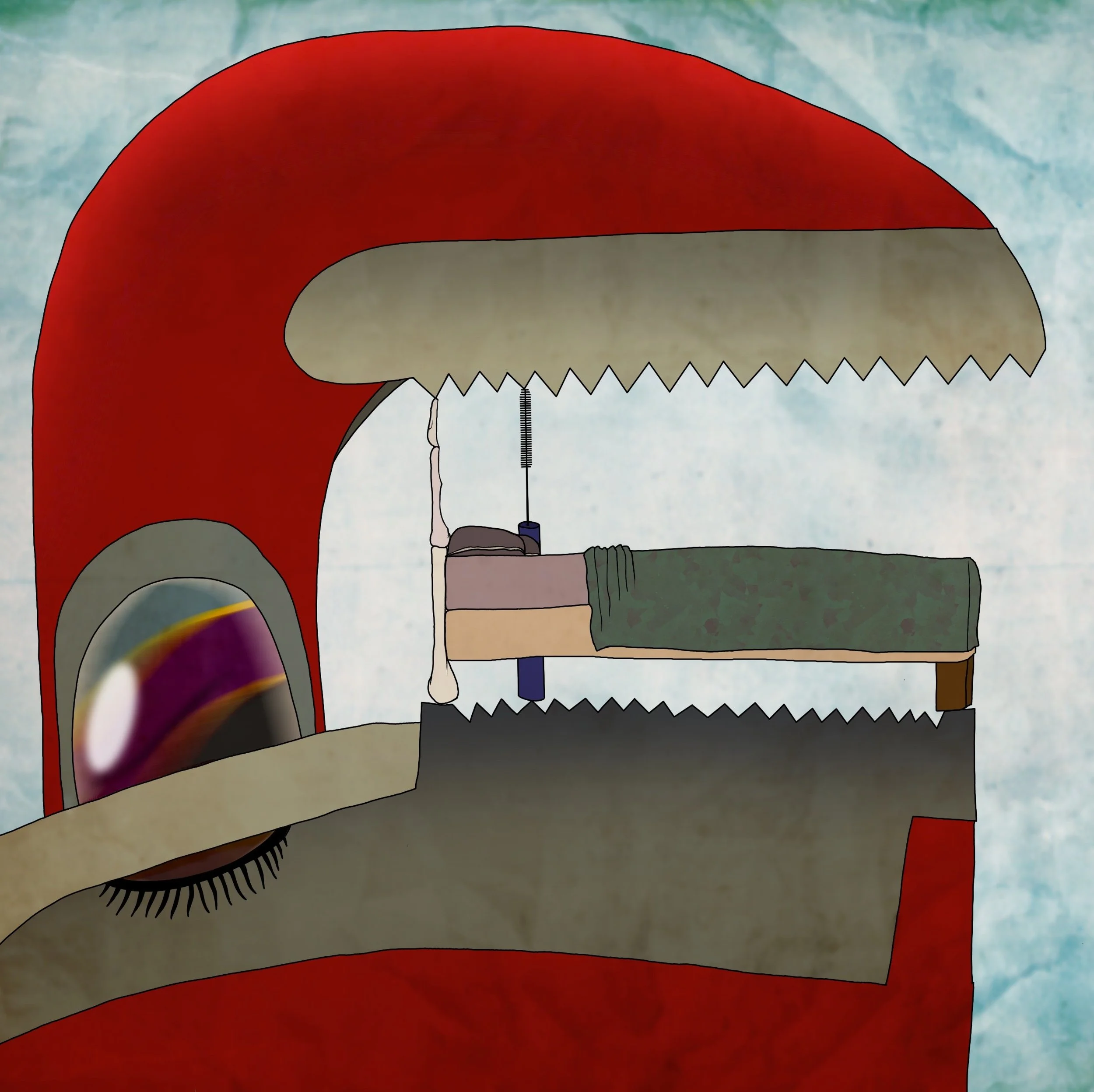

PLEASURE/PRESSURE

Josiah Cox

a disclosure of Melvin Bellwether

Josiah Cox is from Kansas City, MO. He’s a graduate of Yale Divinity School and The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University. His poems are forthcoming or recently published in Smartish Pace, Literary Matters, Bad Lilies, and Commonweal.

Contributor’s Note:

Charles Simic’s description of the prose poem as “a monster-child of two incompatible impulses, one which wants to tell a story and another, equally powerful, which wants to freeze an image, or a bit of language, for our scrutiny” seems close to my own experiences with it. The poem above began with a few images that accumulated in force until the voice that I have come to identify as Melvin Bellwether’s began to speak of them. The narrow prose was an instinctive choice early on. Somehow it felt appropriate to Mel’s consciousness and character. I am less interested in narrative per se than moments of self-disclosure (hence dramatic monologue, I guess) and focused disclosures of reality to the self. Prose might be à la mode in poetry, but often it is either limpid or nebulous, aloof in its own strangeness, easily mediocre. I very much am still figuring it out.

Editor’s Note:

Prose Poem is my most favorite form of poetry. The wall-like prose blocks excite me for many reasons, that they’re so accessible tops that list. In Josiah Cox's “Pleasure/Pressure,” the intricacies of human connections are mirrored masterfully through the lens of working class experiences. Cox intertwines the physicality of the plumbing trade with the emotional labor of a divorce, using the metaphor of fused pipes and stubborn joints to explore themes of resilience and breakdown in both materials and marriages. “I always felt bonding as possible breaking. Pleasure/pressure, you know?” His reflections extend beyond the personal, touching on moments of absurdity and pain that punctuate the aftermath of separation. “After separating, I skewed absurd, like cursing a bag of frozen peas for being cold.” I love how the poem is mysterious and ambiguous throughout but never vague, never abstract to the point of abandon. With a smooth blend of narrative and lyric, the poem is both clever and tender without ever being contrived. The use of objective correlatives in this poem would impress TS Eliot. As Cox navigates the remnants of the speaker’s past—whether it's a cap-less mascara tube or a tent stick—he invites us to consider how the pressures of love can both form and fracture our sense of self.