6 Poetry Collections

as Editing Prompts

Imitation is flattery, but also a great form of bettering your craft.

by Andreea Ceplinschi

Over the years of taking and leading workshops, of offering and receiving feedback, I’ve developed a few favorite editing techniques I always turn to when I get stuck on a draft or when a poem idea doesn’t feel quite right. Consider the following poetry collections both as inspiration and each as a prompt for an editing exercise. Some of these may feel like unusual suggestions, but remember the point is to remove the editing block that often leads to giving up on a draft.

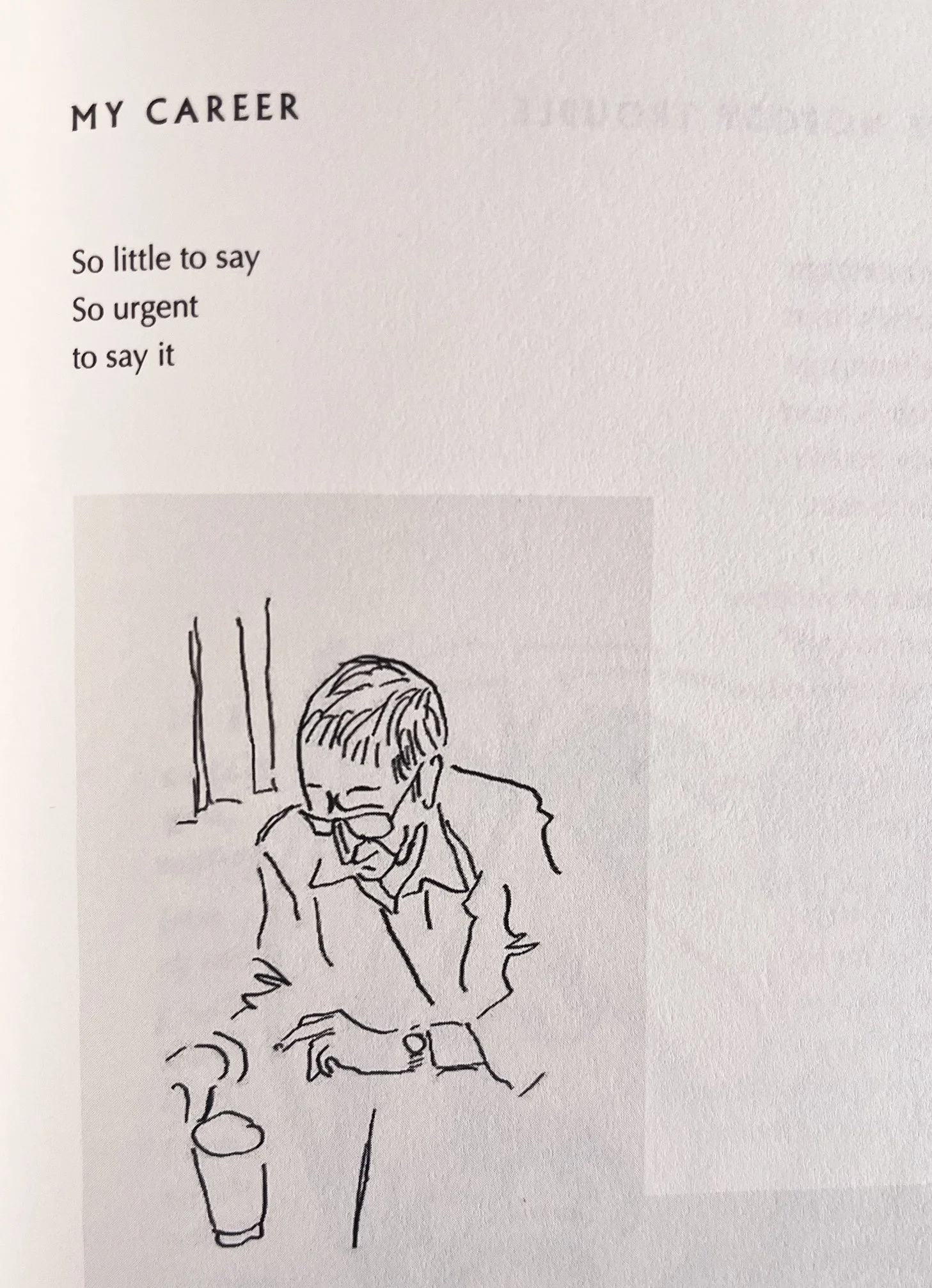

The Flame by Leonard Cohen (Random House, 2019)

This collection goes beyond poetry, including sketches and drawings, song lyrics, diary entries. Though not always in conversation with each-other, these pieces form an artist’s field journal, speaking to the practice of putting ideas on the page, regardless of the medium. Overall, this book is an intimate, chaotic mix of artistic expression, showing that a poet is often more than just a poet, as the desire for artistic expression looks for any type of outlet to be set free.

Editing Prompt: Interrogate Your Message

The first question I ask any peer reviewer looking at a poem is: what do you think this poem is about? In order to create enough distance between yourself and the poem, the exercise is to try to express the message of your piece through a different medium. While this kind of reverse ekphrasis might not be available to those without musical or visual arts affinities, prose will easily be accessible to all writers. Write down your poem as a story. What’s that story? No metaphor, no abstractions, and don’t explain it. Show it. If you’re having a hard time telling the prose version of your piece, perhaps the message isn’t clear to you as the writer yet, so the reader won’t be able to perceive it either.

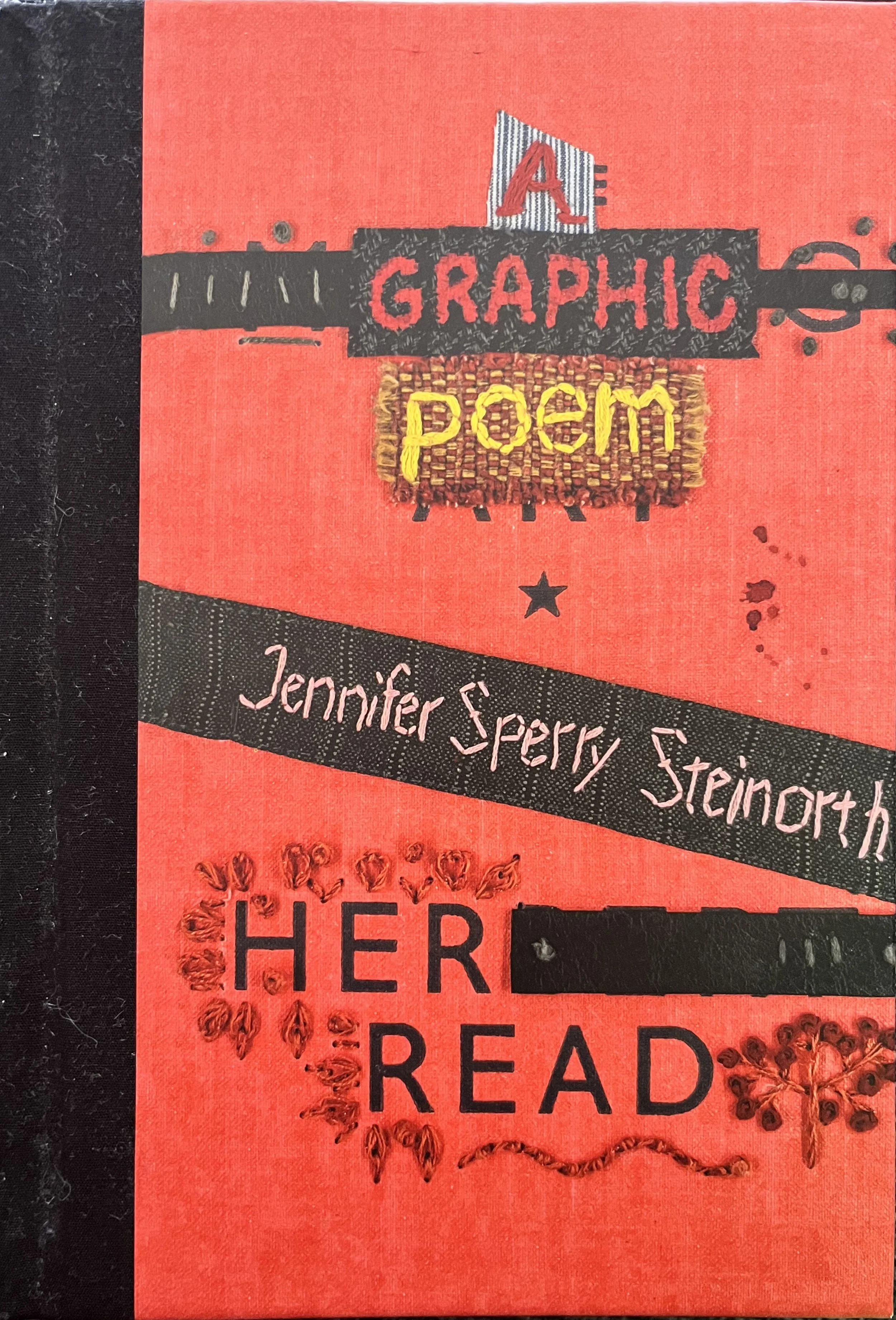

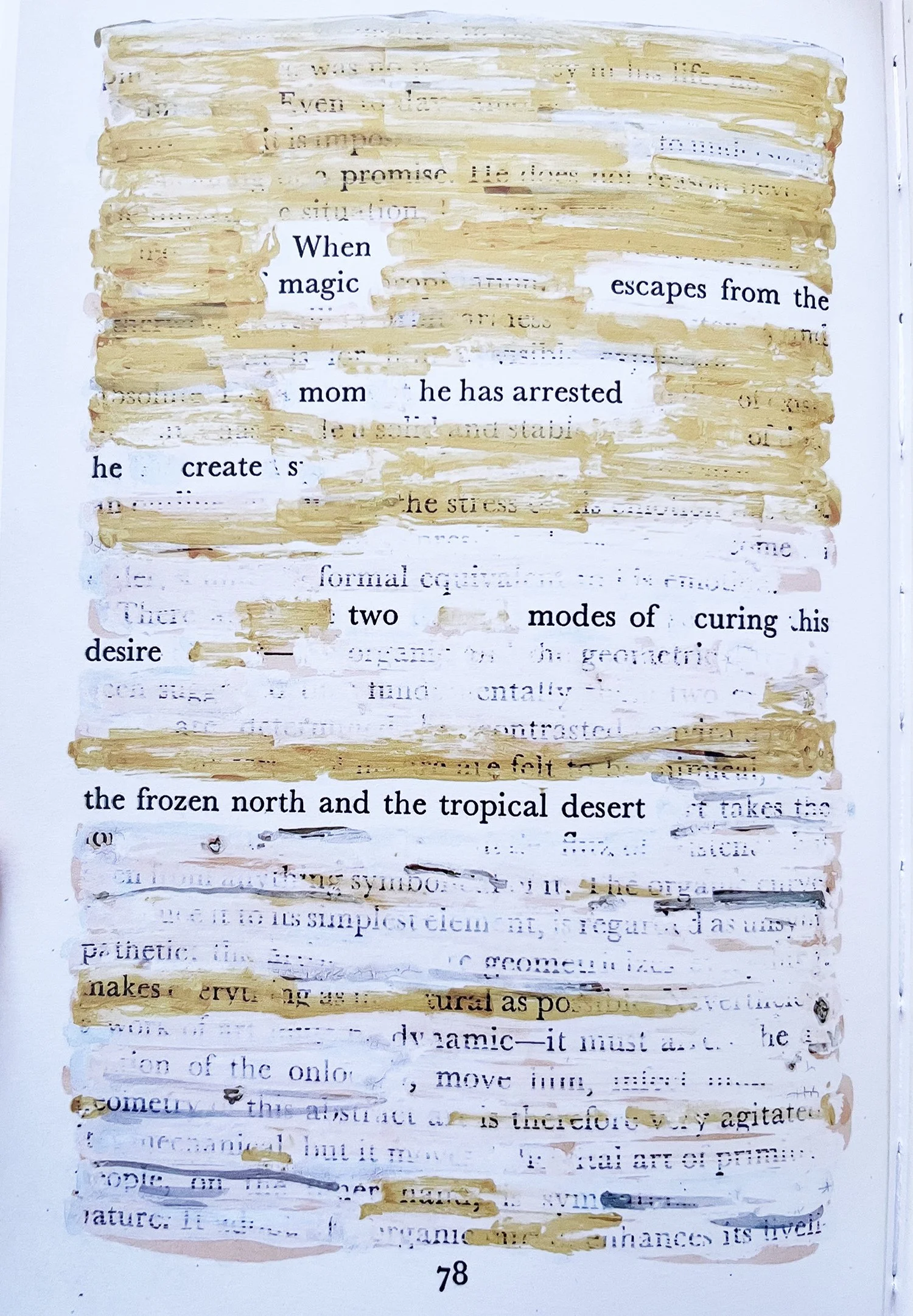

HER READ by Jennifer Sperry Steinorth

This is a book-length graphic poem showcasing one of my favorite editing AND generative techniques: erasure. The source text is The Meaning of Art by Herbert Read and the resulting long poem is a visual treat, as well as a reclamation of message and meaning by replacing the outdated original perspective with Steinorth’s new and original perspective.

Editing Prompt: Clean Up the Vocabulary

I call this the Strunk and White method because it prompts me to focus on the efficiency of the vocabulary I’m using. Erase all adjectives and adverbs and I do mean all, show no mercy. Now locate your nouns and verbs and find their versions most efficient in conveying the message. Rebuild the poem trying to use as few qualifiers and quantifiers as possible. This means focusing on the difference between walked slowly and lumbered, between young woman and maiden. To go even further, play around with changing vocabulary values: verb a noun, weld an adjective to a noun and create a completely new vocabulary element.

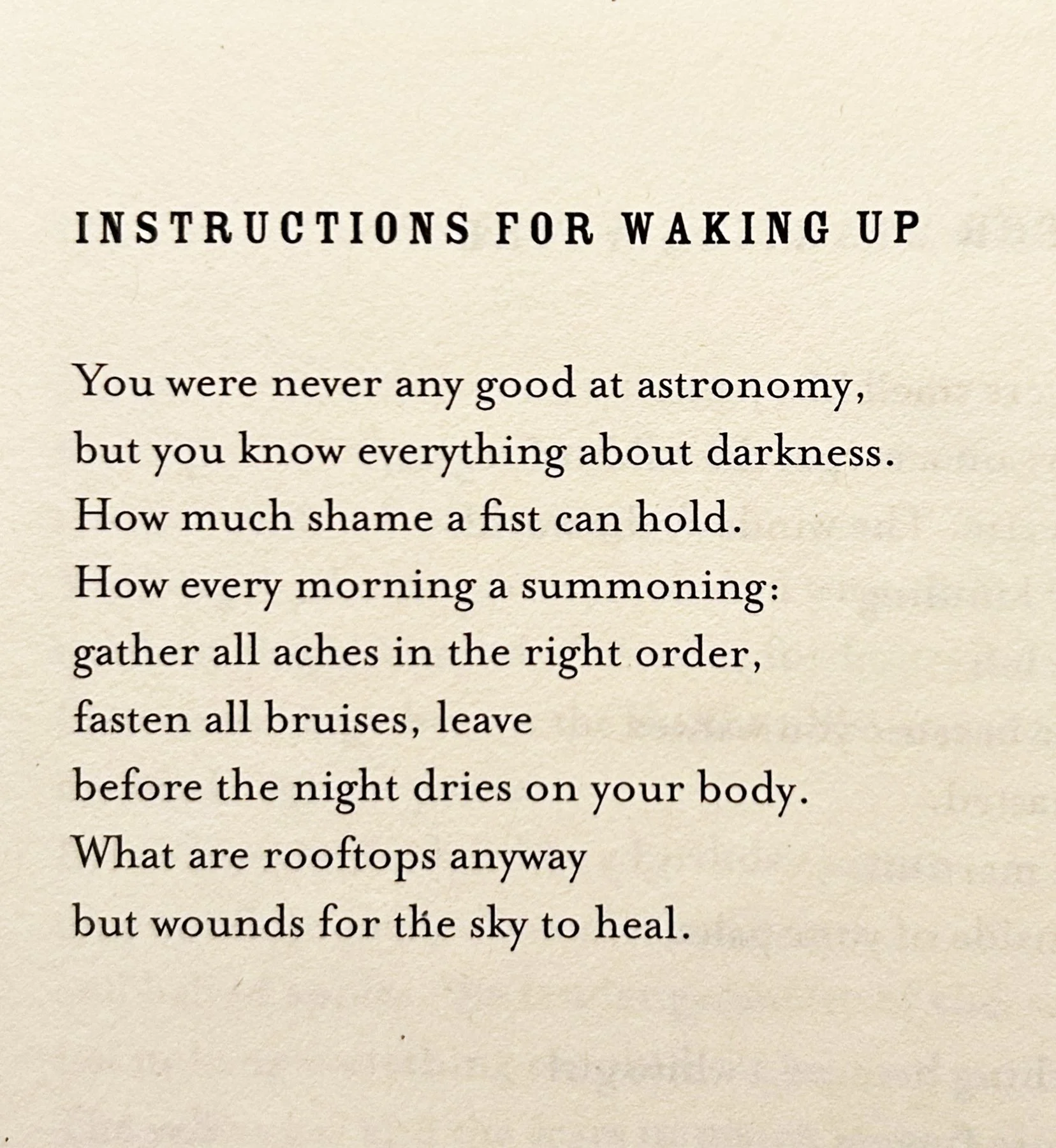

Instructions for Building a Wind Chime by Adriana Cloud

A lyrically delicious collection where tenderness and unexpected whimsy are always in direct address with its audience. By using the instructions format, these poems allow the reader to decide whether the poem is addressed to them or not, depending on whether or not the reader agrees with the instructions. Regardless of the reader’s level of engagement, the effect is that the voice comes through clear and precise.

Editing Prompt: Find the Voice by Finding the Audience

Say you’re already clear about the message of your poem, but things are still not coming all the way together in your piece. Rewrite the piece as a list of instructions, a recipe, or a spell. Whatever format you choose, it should offer a list of steps on how the reader can get to the message of your piece. When you rewrite a piece in the second person, have a very clear image in mind of the you the poem will address. Address the poem to your mother. Write another version addressed to the police. Another version, to a 5-year-old child. Selecting a specific audience will dictate what the poem sounds like, helping you locate the voice of your piece.

Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

More than poetry, this book is testament to the record-keeping power of poetry, a collection of both private and public moments highlighting global racial injustice and tension. Rankine illustrates that tension in a deeply personal way, making it difficult to ignore. The message of inequality this collection explores is well-known, so the focus of these poems is the voice and its nuanced, human urgency: “And where is the safest place when that place / is someplace other than in the body?”

Editing Prompt: Define the Emotional Tension

It’s important to remember that you can’t control how the reader will feel about your poem. The reader will bring their own personal history to the reading, thus shaping the outcome of understanding your message. Your only responsibility is the clarity of the message and the way your chosen speaker feels about it. Write with clarity, from the scar (the speaker in the present moment of the poem), but don’t forget or deny the wound (the event that triggered a need for the message of the poem). Emotional tension is what bridges the two. How does your speaker feel about the wound? Force your speaker to feel angry, despondent, or grateful, and rewrite the poem in that feeling. Explore what that specific tension does to the piece.

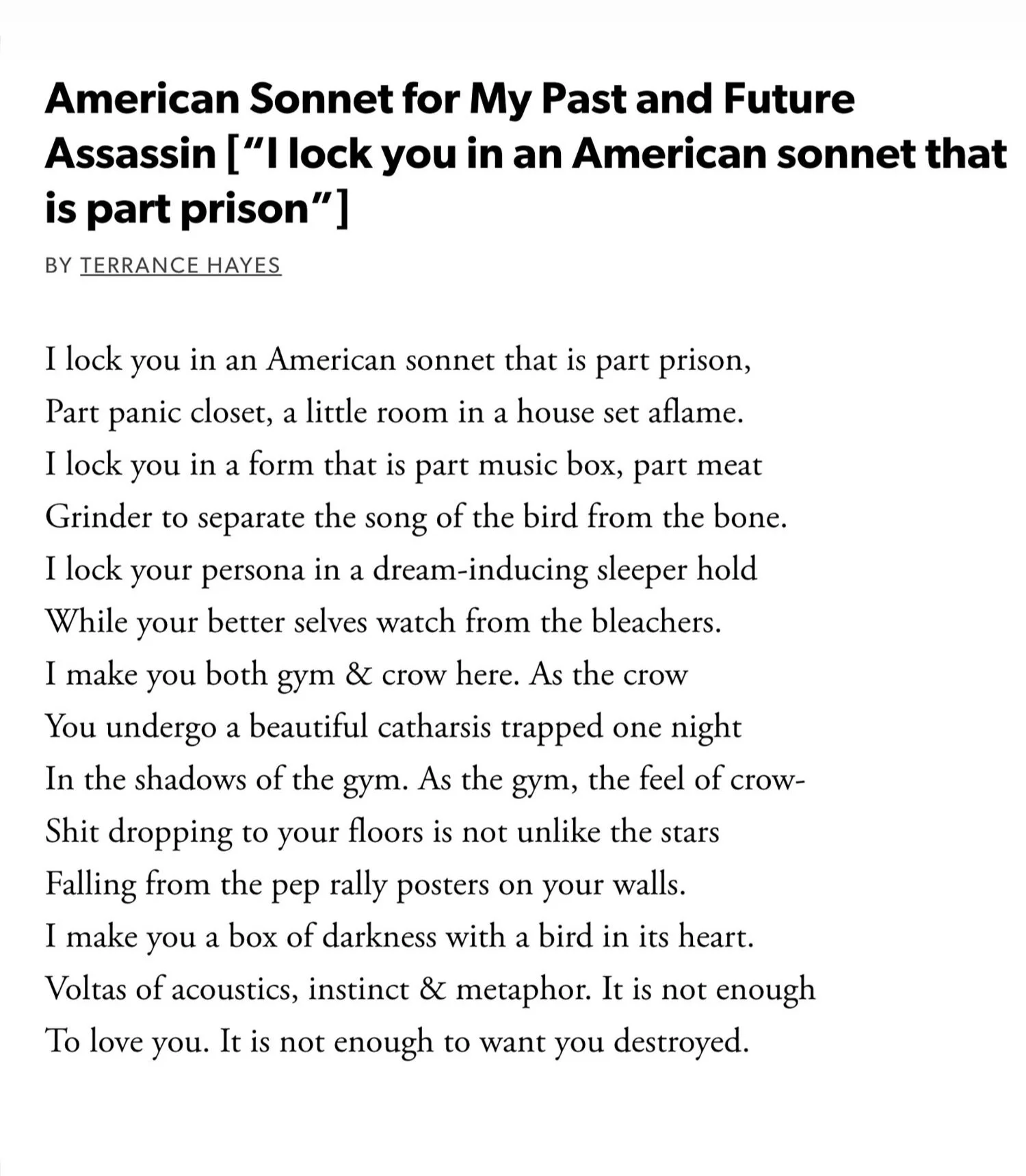

American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes

There is little I can offer in praise of this collection that hasn’t already been said by more outstanding voices in the literary community. These 70 sonnets are a showcase of intelligent and refined emotion from and for the black male existence in a savage environment of increasing danger and vulnerability. Hayes possesses an effortless, yet relentless skill with the sonnet, the form always precise, not a word out of place, each 14-line sequence visually contained as if presenting itself to the world hands-up, as non-threatening as possible, while the content of those lines is sweltering with a whole spectrum of emotion.

Editing Prompt: Refine the Delivery through Form Constraint

This exercise forces you to engage with the difficult task of mastering a form. It’s not enough to know the rules of a particular form like the sonnet, but through practice you may find a different voice in that particular form, much like Terrance Hayes. Forcing the creative mind to adhere to almost mathematical rules unlocks the potential for unusual word and metaphor associations to suit both the message and the form. If nothing else, form play will make you reconsider line and stanza breaks, which in turn could be just what a poem needs in order to move forward.

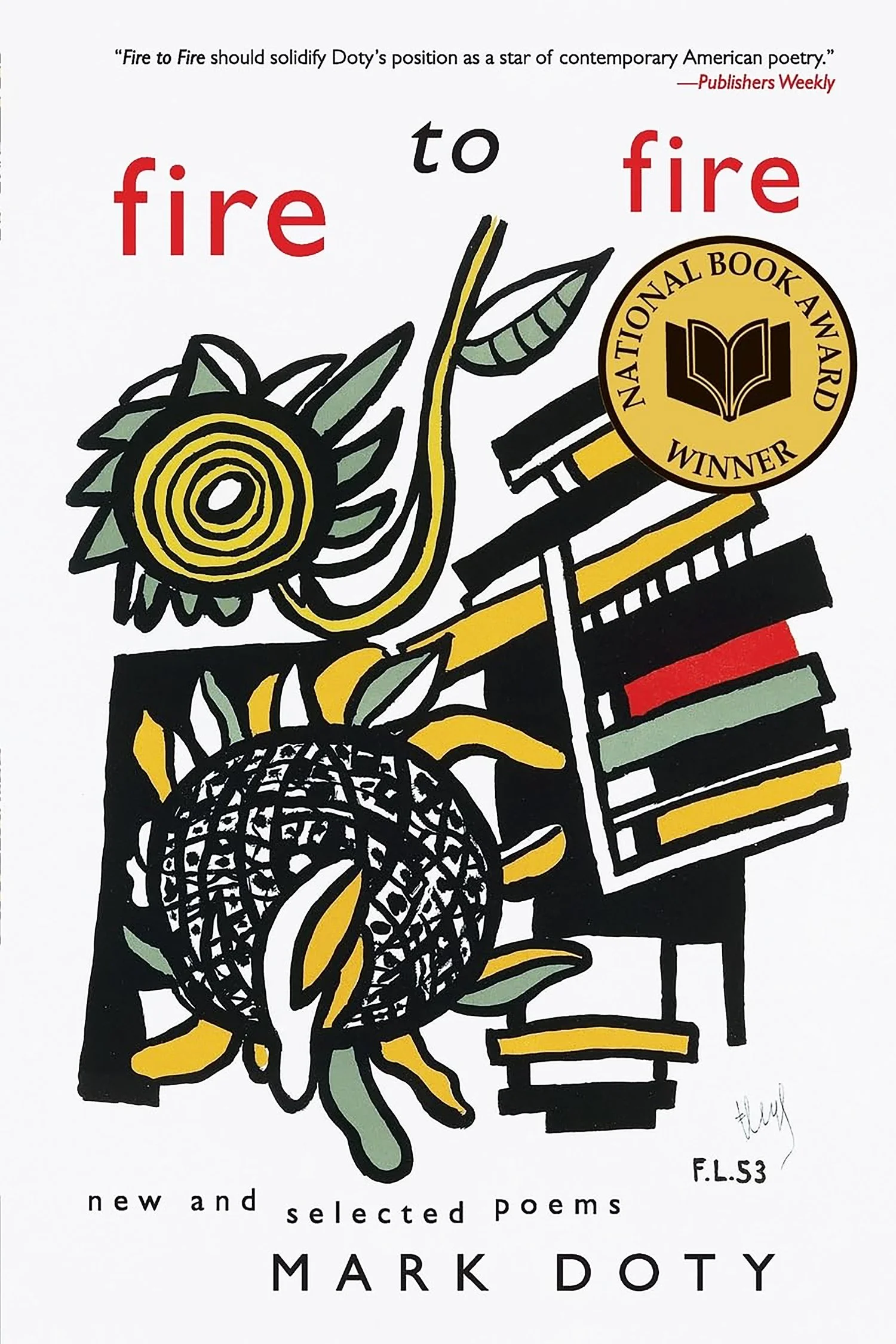

fire to fire by Mark Doty

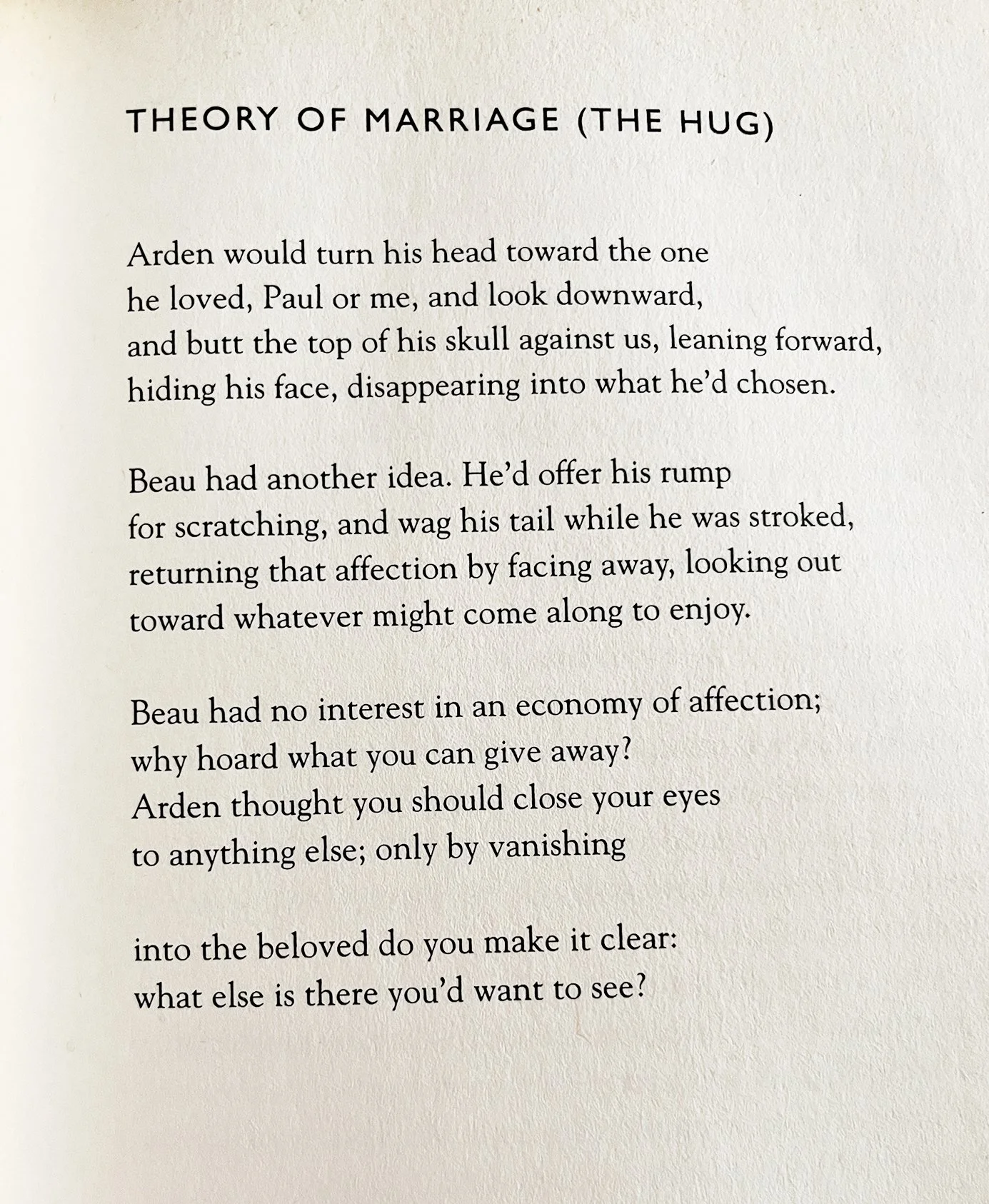

This collection is an ode to clarity and compassion. Doty has truly learned to write from the scar, with empathy for all past and present triggers. His writing isn’t tame, nor does it disregard pain, yet it’s infused with understanding and gentleness, almost as if the speakers of his poems have transcended suffering, thus becoming illuminated. This transcendent light is reflected in both content and form in Doty’s poems. His lines and stanzas are arranged with measured visual rhythm on the page, reflecting the speaker’s state of mind.

Editing Prompt: Conscious and Deliberate Line and Stanza Breaks

While a good rule of thumb is to break the line wherever you need to pause for breath when you read your poem out loud, honing the art of a beautiful line break is what puts that final finishing touch on a well-written piece. Play with stanzas that reflect the relationships in your poem, like couplets for duality, tercets for trinities. In The Theory of Marriage Doty uses quatrains to mirror a relationship between two partners in the two ways his dogs seek and react to affection - four actors, four lines, with an ending couplet suggestive of the “vanishing into the beloved” which makes half of the stanza vanish as well. Take the exercise further and re-break all your lines into enjambments, or break every line after the most important word in that line. The visual aspect of your piece on the page or screen should match the feeling of the poem. When you choose an unusual shape like a justified column or lots of empty space between words, make sure it’s a conscious and deliberate choice because an editor reading that work will certainly wonder why that choice was made.

Andreea Ceplinschi is a Romanian immigrant writer, graphic designer, photographer, waitress, and kitchen witch living and working at the tip of Cape Cod. Her writing includes poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction, published in Solstice Literary Magazine, 86logic, One Art, Wild Roof Journal, The Quarter(ly), The Keeping Room, Bulb Culture Collective, Club Plum Literary Journal, and elsewhere.