7 Poetry Collections

Inspired by Fatherhood

Beyond daddy issues: poetry exploring

the world through a father’s lens.

by Emma Mott

Before we get to the real intro for this piece, here are some beginnings I cut:

1) Look we’ve all got daddy issues, but how are the daddies themselves? This collection of books answers that question for you.

2) Fatherhood takes on many different forms. In fact, some fathers have mustaches. Some have beards. Some are, in fact, hairless. These are the forms of fathers.

3) Fathers, we’ve all got one. Well, biologically speaking anyway. These are some dads who stuck around and wrote about it!

In the last decade or so, fatherhood has bloomed in poetry. As we move away from toxic masculinity and more and more men embrace their identity as a father — a father who is unlike Sylvia Plath’s father, or Kafka’s (for more examples, I did a google search for bad fathers in literature, and there are literally countless lists!) — we get to witness and experience this tenderness through their art. Here’s a list of writers who eloquently share their struggles and joys as fathers. These poets draw inspiration from their children, their fathers, and some create new paths as the first father who chose to stay. While weathering difficult circumstances, like infertility or natural disasters, these fathers love, care for and protect their families. Whether you yourself are a father, have a father, or just want to experience fatherhood in all its complexities, we recommend these books to find inspiration, joy and strength.

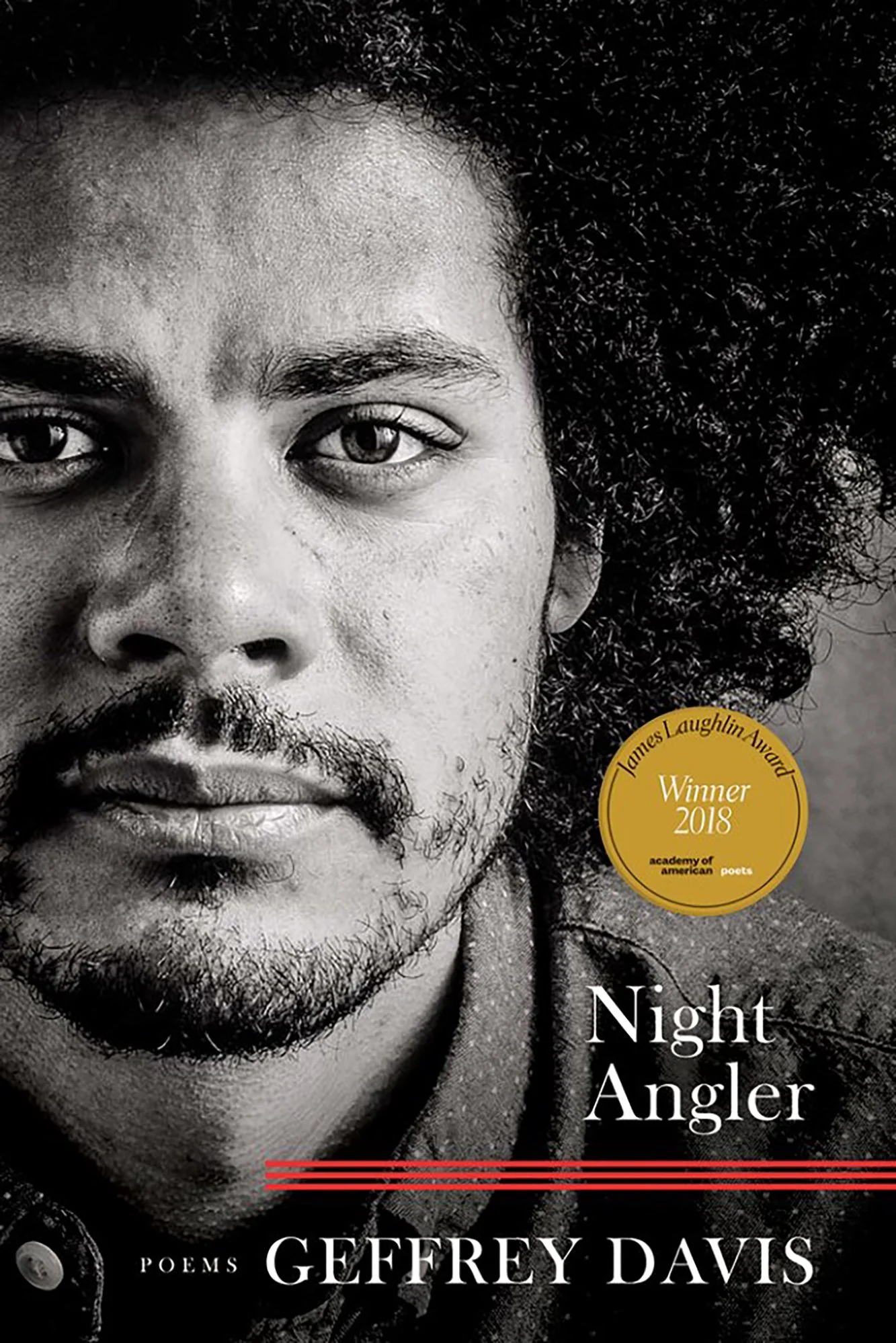

Night Angler by Geffrey Davis

(BOA Editions Ltd., 2019)

Geffrey Davis wades into the dark waters of Night Angler with the familiarity of a skilled fisherman. He knows the darkness here: divorce, addicted and absent fathers, miscarriages, daily and systemic racism. Davis’s speakers know each groove in the blackness, and know the stories that spill from each. And yet, lines in Night Angler’s poems flash like fish scales in a flashlight’s beam through the permeating darkness.

While remembering and honoring these stories, Davis makes the effort to pen and live something new. With the rush of reeds along the riverbed, “the muffled blood-/machine still knocking away,” “coyotes crying” in the night next to freed horse hooves, Davis’ book creates a symphony of love for

“the record [that shows] we invented /

one another: family—a lighted story /

set against the shadow and dawn of distances.”

Writing through and against the cyclical nature of abuse and absence, Davis’s love for his son reads as a thrashing and endlessly gentle light, shining on something that looks like hope. Towards the end of the collection, he asks, seemingly as much to himself as the reader, “Do you hear / what it means for me to sing my son to sleep?”

A book to read and reread.

Patter by Douglas Kearney

(Red Hen Press, 2014)

Patter is a rare book that delves into the truth of the male experience of infertility.

Douglas Kearney’s truth? A brutal eight-year long journey through miscarriages, IVF procedures, and eventually fatherhood. His form? Varied. Patter is not just made up of words, but of spacing, font, size, angle, shapes. Meaning arcs over the pages where language fails.

And language does inevitably fail, as Kearney wrestles with in the book.

One of Patter’s poem, “The Miscarriage: A Bar Joke,” goes like this:

“two guys walk into a bar. first guy says "yo guy, why so down?" second guy replies, "my wife just had a miscarriage." first guy says "I know exactly how you feel, I just had my girl get an abortion!"”

In conversation with NPR, Kearney disclosed how he wrote “The Miscarriage: A Bar Joke,” based on two real-life experiences. His initial response to those interactions was “this huge mix of feelings, of this anger,” but then he realized there was a bigger question at play: “How are men supposed to talk about this? What are we supposed to say to each other when this happens?”

Instead of pushing against the blank wall of language’s lack, Kearney got creative. Kearney is a poet who knows he will perform his poems. Allegories, “Father of the Year” competitions contrasting Darth Vader with Noah (of the ark variety), minstrel shows, reality TV interviews all cover the pages of Patter. Like the best performers, Kearney creates art that both demands and requires your attention.

Life and death live where language fails. In Patter, Kearney brings his journey to life.

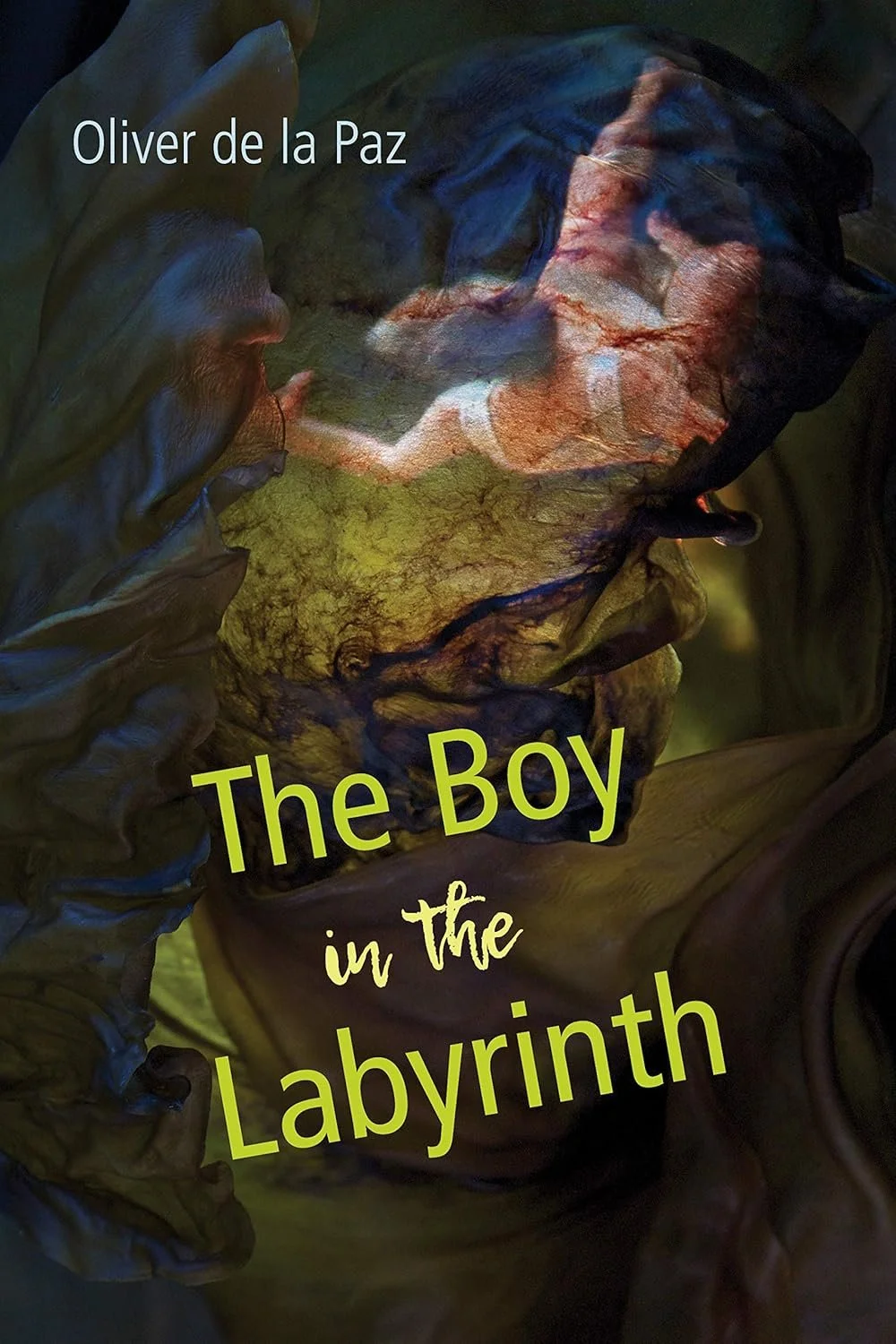

The Boy in the Labyrinth by Oliver De La Paz

(The University Of Akron Press, 2019)

Oliver De La Paz harmonizes his writer’s soul and fatherly love in The Boy in the Labyrinth to paint every nuance of his sons in the richest colors. He opens with a series of understandings - truths he has come to accept as the father of two sons with autism.

One of these understandings is how Paz started writing a series of poems about a boy trapped in a labyrinth and eventually realized he was writing about his sons. The poems are patchwork, episodic and written as immersively as a fantasy novel; at times, it feels as though you might be able to reach out and touch the “spider web lattice,” or hear “water’s uncurled parabolas with each metronomic drip” right over your shoulder.

As Paz and his wife tried to assess “this and that,” “the paperwork was labyrinthian.” So assessment questions break through the rich story of the boy in the labyrinth and Paz answers them with honesty, defying their categorical tendencies with language better encapsulating real life. One question asks, “Does your child not seem to listen when spoken to directly?” and Paz responds, “We call it dappled thoughts. He is constantly dappled— here and not here. He is a thrush hidden in the sage.”

Every page is a love letter to his family with all its complexities. The vulnerability inherent in living with and taking care of vulnerable individuals made Paz reluctant to pick up the pen, but he did. The Boy in the Labyrinth exists, and the world is better for it.

Above Ground by Clint Smith

(Little, Brown and Company, 2023)

Jazz music swings across the pages of Clint Smith’s Above Ground; your soul boogies in response.

At a conservative estimate, at least 90% of the poems in Above Ground left my mouth gaping at the sheer narrative skill and outrageously brilliant perspectives. Above Ground shoulders the “soft hum of history” to stride across this narrative with hope and joy, sans naivety.

In one particularly vivid piece, “Dance Party,” Smith describes a kitchen in controlled-chaos post-dinner, as his daughter starts “flinging her limbs like an off-beat octopus” and his son is “doing the robot… / or is being eaten by a robot.” The father begins an ill-advised worm on kitchen tile, which can only lead to “a robot / and an octopus riding the back of a worm / who will certainly need some Tylenol before bed.” As a father of two, Smith looks at his children with unbridled joy and nobody - nobody - writes joy better than Clint Smith.

In fact, you might have a case that very few write better than Clint Smith, period. Both the ecstasy of love and the tragedy of life present themselves deftly. Smith’s pen takes on so much of our modern world, from “half-eaten Pop-Tarts” of school shooting victims to the “200 Civilians [that] Have Just Been Killed by U.S. Military Air Strikes.” The opening line of “When People Say ‘We Have Made It Through Worse Before’” is “all I hear is the wind slapping against all the gravestones / of those who did not make it.”

Who should this book be recommended to? Frankly, anybody Above Ground.

(Clint Smith's local bookstore offers autographed copies here.)

Attempted Speech and other Fatherhood Poems by Kola Tubosun

(Saraba Magazine, 2015)

Writing from Ikate, Nigeria, Kola Tubosun opens his chapbook, Attempted Speech and other Fatherhood Poems, with a brief disclaimer: “I believe it quite unlikely that anyone is able to fully express fatherhood in words, so I have not tried it here. In any case, the English language is limiting enough.” Instead, he opts for “personal reflections on [fatherhood] and other related histories. . . and expectations of yet unfolding futures.”

Tubosun’s pen follows the major milestones of growth: birth (“[a wait] brings with it. . . a human bundle / many months removed from the wetness of earth”), first words, and the first “unsure steps of a walking child.”

Throughout, Tubosun showcases his talent for sound. Each poem mixes syllables and syntax in a way that makes you go back and whisper it again under your breath. In “Independence Day” a child’s “sugar rush” is a “Thunder toddler, child chuffery, kid clusterfuck.” The opening lines of “Blank Slate” read “What does one write on a / Brown slate of bouncing flesh?”

In the titular poem, “Attempted Speech,” the speaker explains how people become part of the world: “tongue first, approaching language in angry bits / like a hundred men fighting.” Tubosun’s collection encapsulates a struggle between new life, language and meaning in his chapbook, and comes out on the other side singing.

Fatherhood by Caleb Klaces

(Prototype Publishing, 2019)

Caleb Klaces mixes prose and poetry to deliver his novel Fatherhood, a work of verse fiction that brings his reader from pregnancy to delivery room into life with a young daughter. Early on, the unnamed new father establishes two possible pre-set paths for himself in this role: “intimate but brittle exuberance or benevolent but distant strength.”

Neither seem to fit what he calls “the lingering startle of his shock when he first looked at his child and thought, “I have absolutely no idea who you are!” In lieu of the predetermined dichotomy, he creates three “ambitions,” the primary is to “not betray that uncertainty.” Stripping away the traditional narrative beats, Klaces circles back to an idea of “work without a goal,” where “the reward [is] the labour.”

In that effort, Fatherhood mixes between history, memory and autobiography. When the family’s house floods, Klaces traces one plotline where the unnamed father visits the house with his wife. The two “waded and steadied one another in the brown current,” then “dragged [themselves] up the dry steps,” where they “made love among the ruins.”

In the very next sentence Klaces doubles back, writing, “For six drafts that [plotline] was the truth. But now I am ready to admit that when our house flooded, I stayed, even in fiction, with my mother and stepfather.”

The father faces impossibilities throughout this story - the destruction of his home, the wonder of new life and with every rewrite, his story honors the beauty in uncertainty surrounding Fatherhood.

Ways We Vanish by Todd Dillard

(Okay Donkey Press, 2020)

Poet of the Week and Twitter icon Todd Dillard opens his chapbook, Ways We Vanish, with a question that suggests an ending: “What is grief?”

This question remains central throughout, as a variety of speakers look at different ideas. Dillard remarked in an interview with Long Leaf Review, “that grief is absence, yes, but grief is also additive, and what it adds is impossibility—that a loved one who remains very much alive within one’s interior ceases to be alive in the external world, and you can disappear trying to navigate the way this absence flourishes inside you while clashing with the world around you.” Change can bring about absence and hope, and Ways We Vanish steeps in this tension.

The chapbook is separated into two parts. The first follows a son’s relationship to his mother and her passing; the second picks up in the grieving, with the birth of a daughter and the process of caring for an ailing father. Ways We Vanish showcases a transformation across quintessential life moments, a look at maturation from boy to man to father. Dillard’s writing is clear and brilliant, infused with touches of magical realism. In Ways We Vanish, grief and the obscurity of memory become components of wonder.

Emma Mott graduated from the University of South Florida with a degree in creative writing and psychology. After working as an art teacher at the Jacksonville Public Library, Emma moved to Spain, where she now instructs Basque people on best practices for differentiating between alligators and crocodiles in the guise of delivering English lessons. She also reads for the indomitable and relentlessly wonderful force known as ONLY POEMS.