9 Poetry Collections for Navigating

Life with Chronic Illness

Poetry as medicine for the ailing body, mind, and spirit

by Emma Mott

This summer, I had exactly three friends — a side effect of seasonal work on a small island. It happened that one of them suffered from a severe form of endometriosis, and the pills - and there were so many pills - never worked quite right. Side effects here included an airlift to a mainland hospital and being swallowed in blankets on our last night together. The twist of pain intertwined with summer and language as we tossed different poets back and forth in scrubby grass and rocky beaches.

This reading collection list is a side effect of that search. These poets each bring vivid and honest voices to different aspects of illness: some mental, some chronic or cancerous, and one from a caretaking perspective - including a special double feature at the end. Whether you suffer from an illness or love someone who does (and you probably do), I hope you find life in these poets’ collections.

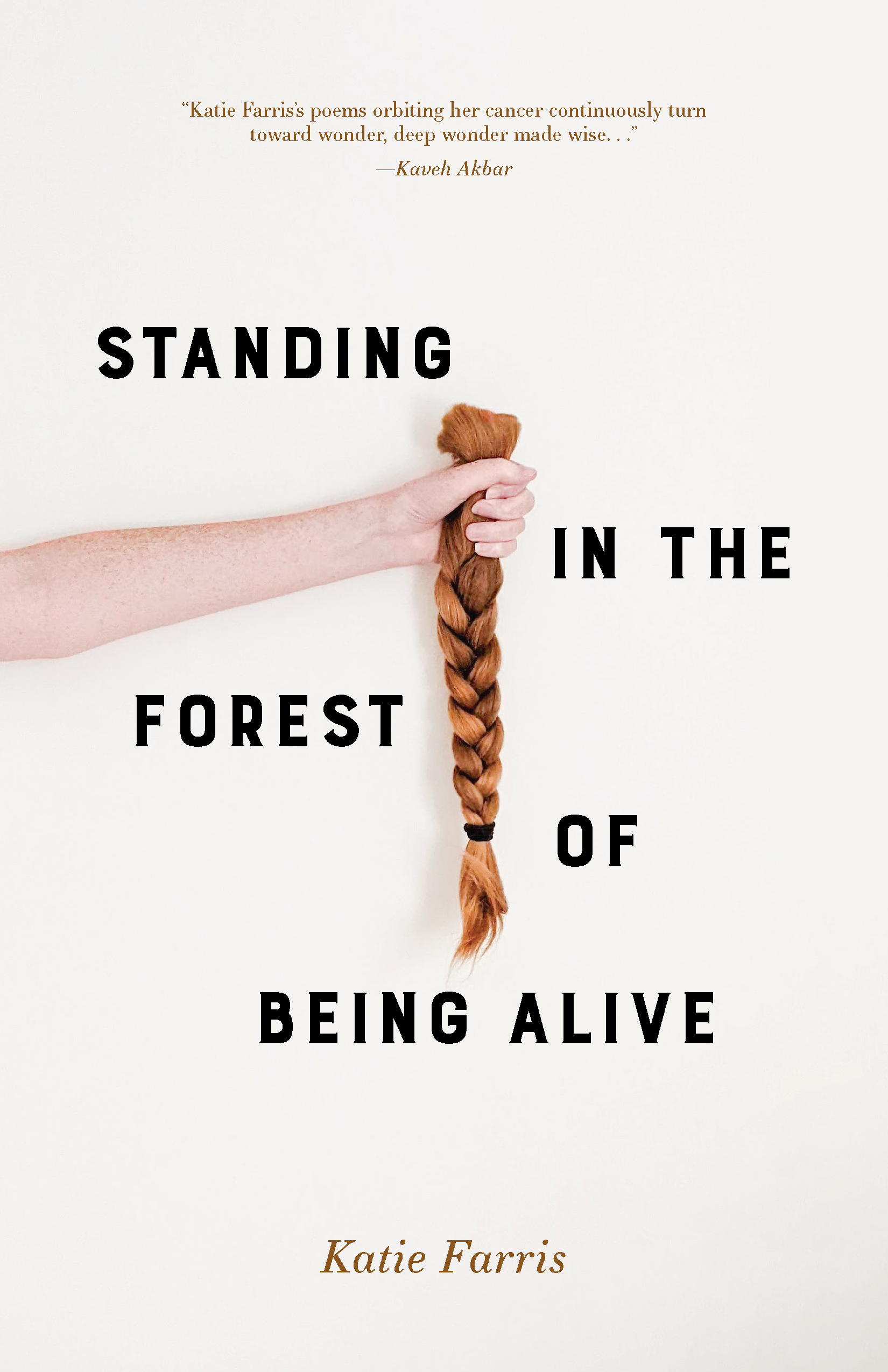

Standing In the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris

(Alice James Books, 2023)

Katie Farris’ book, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive, follows her journey with breast cancer through the stranger’s stares, chemotherapy, port surgery, and a mastectomy. For Farris, this collection seems not only to be a celebration of survival, but a steppingstone toward it. In “The Wheel,” Farris writes,

To train myself to find

in the midst of hell what isn’t hell

I grub at the roots

of words.

This sentiment is again exemplified in “To the Pathologist Reading My Breast, Palimpsest,” as Farris transcribes a doctor’s note, then riffs:

Dear Doctor—you’ve done my work for me in your first line

with your tidy slanting rhyme of specimen and formalin.

Another book of this caliber might be described as translucent with authenticity, but Farris returns and returns and returns to the tangible of the body. In “To the God of Radiation”, the speaker

[finds] in the mirror a woman - breastless, burned - who,

in an advisory capacity

asks, How much do you/ want to live?

Farris takes a pause - two line breaks - then writes: “Enough.”

Standing In the Forest of Being Alive is a beautiful ode to the brutal art of endurance.

Deluge by Leila Chatti

(Copper Canyon Press, 2020)

Born to a Catholic mother and a Muslim father, Leila Chatti’s collection, Deluge, follows a woman as her body inexplicably leaks uterine blood for years on end; in “Haemorrhoissa’s Menarche”, she writes, “I wanted to be a woman / until I was.”

Chatti opens this collection with a reimagined picture of the virgin Mary, “her body ordinary / and so like mine” (“Confession”). From the vulnerability of the gynecologist office and surgery to the intimacy of a relationship and the despair of fertility struggles, Chatti’s ears never turn away from a greater power. In “Testimony”, she writes, “When asked my religion I answer surrender.”

Not only a look into chronic illness, but also womanhood in the context of spirituality and religion, Chatti builds a complex look at human reaction when life turns into something we do not understand.

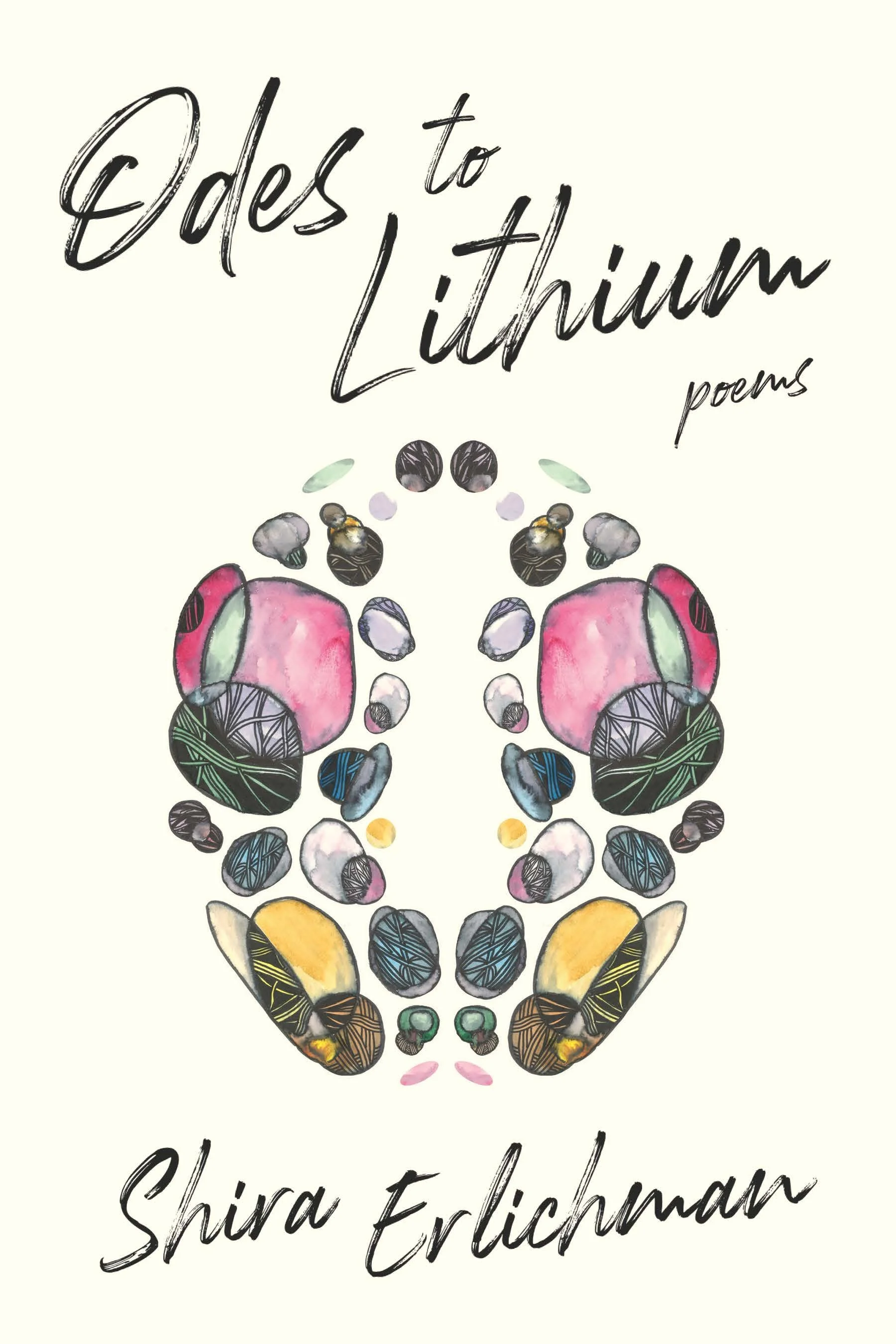

Odes to Lithium by Shira Erlichman

(Alice James Books, 2019)

Through simple language and a bursting imagination, Erlichman invites the reader into a journey with bipolar disorder and its sprawling side effects: “hospitaljail”, the come down from manic episodes, how friends react to the diagnosis, and more.

Early on, in “Mind Over Matter”, the speaker warns - or maybe just informs: “If you don’t have blood / on your hands by the end of this you weren’t / listening.” Her poems bring to life Phineas Gage with stake still stuck in skull, a horse whose “coat is Van Gogh’s Starry Night”, and the titular lithium itself (“Perfect”).

In the penultimate poem, “Pink Noise”, after a series of seemingly unrelated moments - unbelieving friends, notes on language, satiric suggestions for “card games for one person” - the speaker presents a scene: “after a show an audience member says to me, ‘I just / wanted to introduce myself, I’m one of us.’” That pronoun, “us”, crystallizes the privilege it is to read Odes to Lithium. Erlichman has written an intimate guidebook to the learned language of bipolar disorder, inviting those unfamiliar to a chance to bear witness, and to those familiar, a comfort to see art made of these familiar signposts.

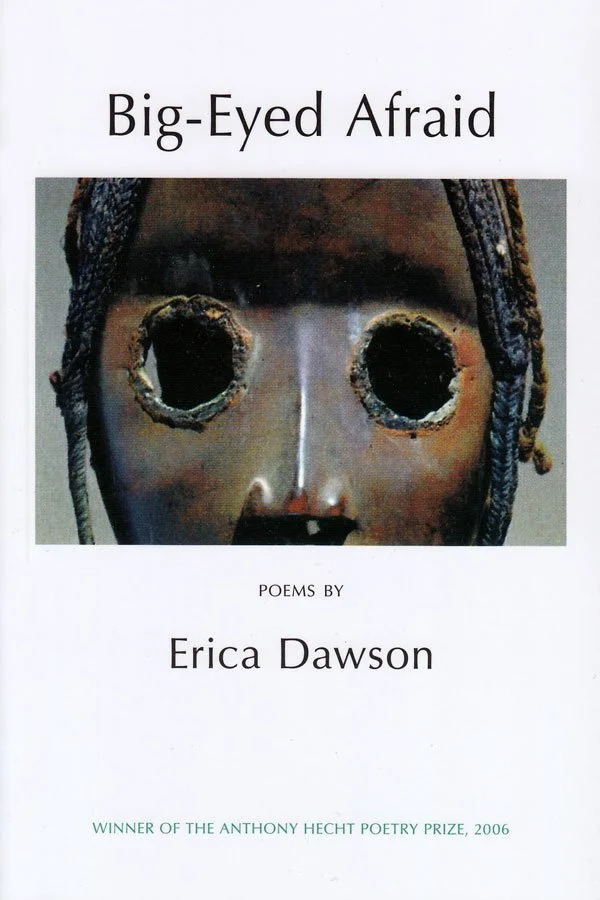

Big-Eyed Afraid by Erica Dawson

(Between the Lines, 2007)

Erica Dawson deftly submerges the readers of her collection, Big-Eyed Afraid, in details of an inherently American landscape, reckoning with race, genetics, and identity. Several of the poems follow experiences with bipolar disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder, and the book itself can be construed as a look at suicidal ideation.

Each word in Big-Eyed Afraid is etched with needle-point precision, but the language twists so fluidly that each imaginative leap comes across as both surprising and inevitable. Her electric vocabulary stretches and balances in tight lines as she explores form, utilizing the rondeau, ballade, and rhyme royal. In “DrugFace”, Dawson writes of driving during an episode,

But this episode

Is mine: a whirlabout

Inside the yellow lines,

Horns trumpeting, so loud, like it’s

Elysium till it remits

To fog, tears, rain.

Smacking with originality, Big-Eyed Afraid is a stunning achievement of stark honesty.

Four Reincarnations by Max Ritvo

(Milkweed Editions, 2016)

Four Reincarnations by Max Ritvo demands your attention - not just because it bursts onto the scene as Ritvo’s debut book, but because each line is tantalizingly crafted, images surfacing and breaking onto the page like waves on the beach. As Ritvo faced down Ewing’s Sarcoma and his impending mortality, he claims “no madness but the one of life” (“The End”). He titled his book Four Reincarnations because, as he told The New Republic,

reincarnation is sort of a defiant screw you to my cancer and death. If I can have four reincarnations I can have four hundred.

In this collection we peer into just four of the reincarnations Max Ritvo experienced and witness abundance, as Ritvo paints both the heartbreak and wealth of love and life. In “Poem About My Wife Being Perfect and Me Being Afraid” - a moment for the title - Ritvo writes,

You have my thoughts faster than I can.

The mouth made from our lips

pours chilly water

out the pipe.

In “Stalking My Ex-Girlfriend in a Pasture” he writes of the desire to “take back the hide she took / to be the sheet / on my eternal sickbed.” Addressing friends, therapists, exes, and family, it seems Ritvo pours every facet of himself and a vivid spirituality into these poems, creating an ocean of meaning and hope.

Extracting the Stone of Madness

by Alejandra Pizarnik

Translated by Yvette Sigert

(New Directions, 2016)

The same way light refracts through shattered glass into a sparkling array of different colors, Alejandra Pizarnik seems to refract the darkness of mental illness, loneliness, and despair through short lines and fragments of prose in her collection, Extracting the Stone of Madness. Beautifully translated by Yvette Sigert, Pizarnik’s work follows her struggle with anxiety and depressive episodes. In her poems, Pizarnik reckons with her sense of self, pushing against constraints of language - once writing “I’m going to hide behind language / And why is that / I’m afraid” (“Cold in Hand Blues”) and describing a vague other as “not scared of the dark / ambiguity of language” (“Psychopathology Ward”).

At times disturbing and at others haunting, but always meticulously crafted, Extracting the Stone of Madness may not be the most comforting book on this list, but it remains a compelling study of mental illness presented in art.

As For Life by Marilyn McViker

(Redhawk Publications, 2022)

As For Life draws from Marilyn McVicker’s experience living with a rare life-limiting primary immune deficiency. This collection wrestles with the limitations of the body, a palpable frustration in the pages. She lays bare the details: itchy wigs, lack of awareness, and “the cup that has a straw or doesn’t” (“Celebrate the Body”). In “The Body”, McVicker writes of aging - of seeing “her [mother’s] face sinking into jowls and neck.”

Throughout the frustration, pain, and fear, The North Carolinian mountainscape pushes back. In “Sometimes”, the speaker softly recites, “katydid, grasshopper, cricket, gnat” as a meditation, lists of the wildlife anchoring through the fluctuating web of a future to be grieved.

Throughout this collection, McVicker circles a sense of peace, even despite. As For Life doesn’t have all the answers and doesn’t pretend to either; its poetic strength lies in a blunt honesty that builds into a moving moment of catharsis.

When Jay Hopler received a cancer diagnosis with a two year prognosis, he thought, I have twenty-four months to write my next book. That book would become Still Life. His spouse, poet and renaissance scholar Kimberly Johnson, started penning a separate collection about her experience at the same time, which would become Fatal.

Despite the circumstances, Still Life is quite funny. “meditation on folklore: a coda” opens with the brilliant line, “fuck bigfoot” . . . “i haunt my own / damned house”, and then goes on to describe Bigfoot as “some backwoods booger- / man.” Within and between every laugh, Hopler writes with equal verve and sincerity. In “love & the memory of it”, the speaker describes his future wife:

her light like a struck string fretting its zing

against the pic-

nic tables

may that be the music you hear

when they unplug the ventilator.

Where Hopler strays more reflective on the hereafter, even with his humor, Johnson presses into each moment in with a sense of the here and now: a son’s hunting trip with his father in the poem “Familial,” a girl’s menarche and ensuing “horror” in “Female,” and a woman’s experience giving birth to her “own / Diffusion” in “Farrow” - each vivid, crafted narrative juxtaposed by statistics of death. These actuarial charts accentuate Fatal’s quintessential question: how can it be possible to bear the extent of life’s inherent pain? In the final poem, “F-Word”, the speaker settles a balance as she describes loss as “the principle / Of love”, while telling her companion, “You are dear, Dear / One, because of the expense.”

To quote from Johnson’s poem “Frogs”: though both Johnson and Hopler are “up against” impossible challenges, they are “resolute as fuck to poem / it first.” Kick-ass poets.

Emma Mott graduated from the University of South Florida with a degree in creative writing and psychology. After working as an art teacher at the Jacksonville Public Library, Emma moved to Spain, where she now instructs Basque people on best practices for differentiating between alligators and crocodiles in the guise of delivering English lessons. She also reads for the indomitable and relentlessly wonderful force known as ONLY POEMS.