October 28, 2024

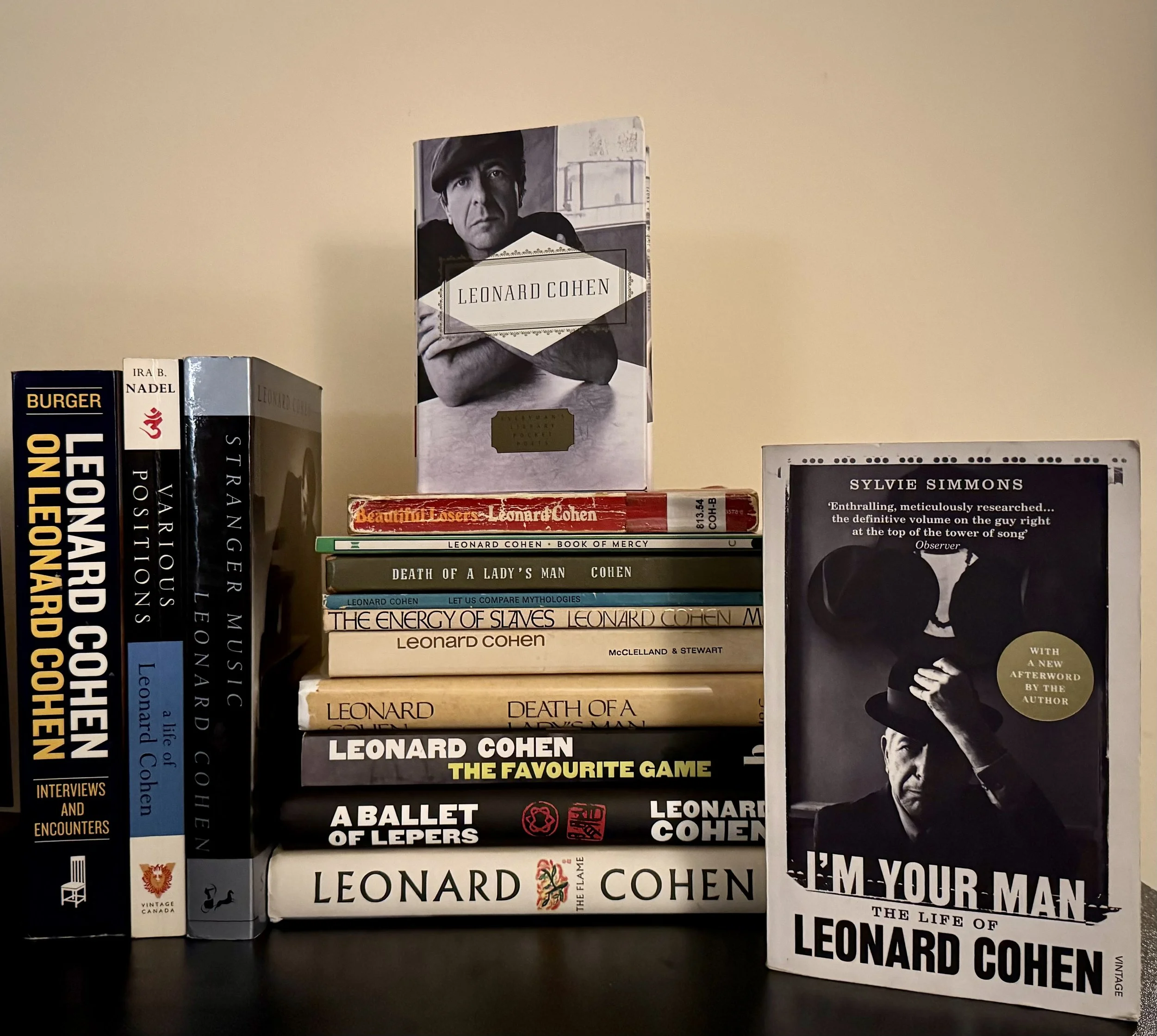

All of Leonard Cohen’s

Books Ranked

a subjective ranking of all of LC’s books

by Karan Kapoor

with Sophia Guerriero, Hanna Houllion, Harry Hew

Leonard Cohen holds a profoundly impactful space in both the literary and musical world as one of history’s most beloved artists. Even years after his passing, his legacy and catalog continues to open the hearts of old and new generations alike. His status in the “tower of song” is undeniable, and his influence on literature lives on in grandeur. I owe so much of the ways I think and move through this world to Leonard Cohen — he truly paved the path for many of us. I’ve read each of his books multiple times and feel immensely close to them all. I have a shrine in my house for Cohen and doing this ranking feels silly — it’s not different from lining up your sons and daughters in an ascending order of love. Yet, below is a deeply subjective ranking of all of Cohen’s books. For the purposes of this list, Selected Poems 1956–1968 (1968) & Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (1993) have not been considered, but both serve as a general starting point to his collections. Okay, here we go!

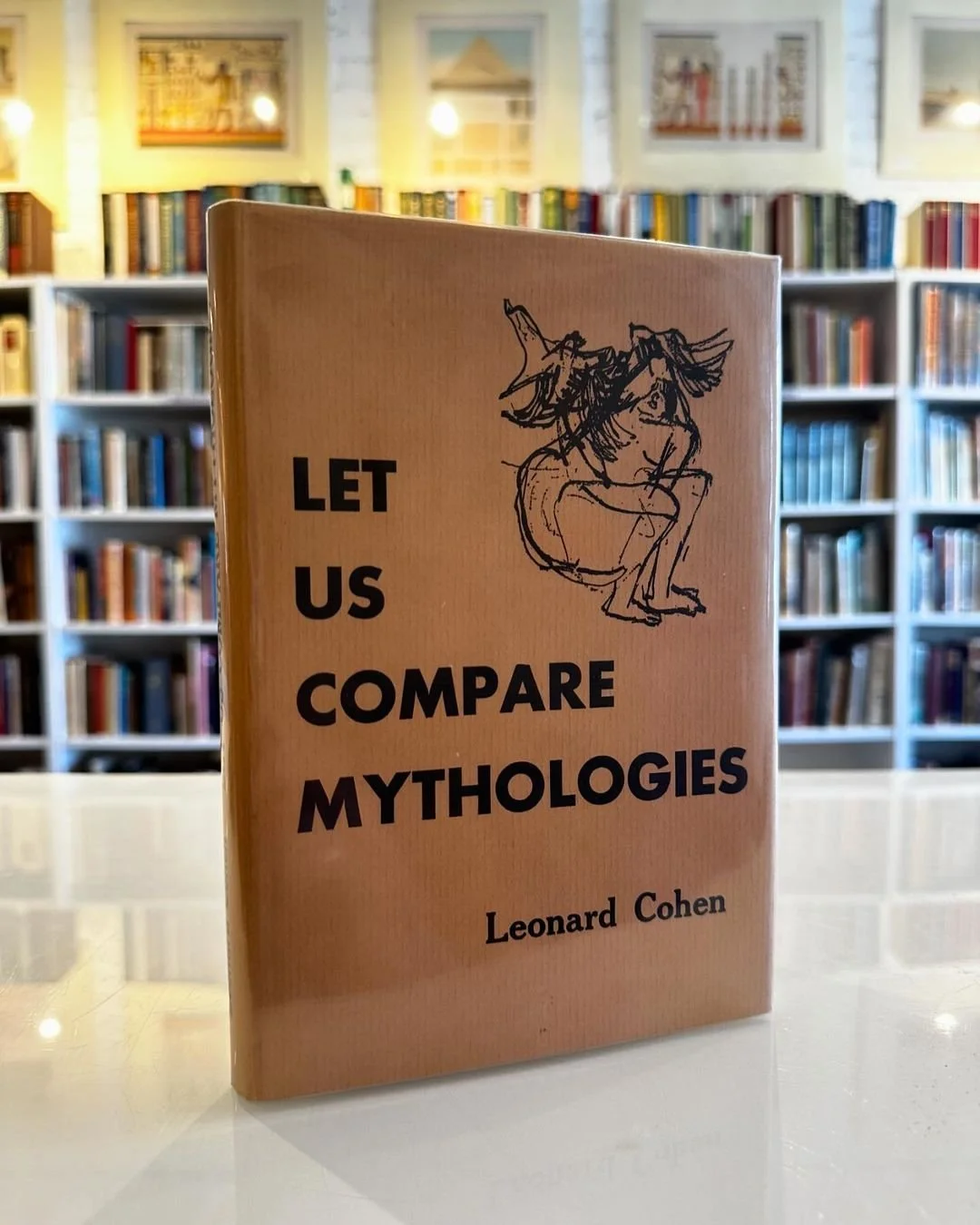

12. Let Us Compare Mythologies (1956)

Leonard Cohen on Let Us Compare Mythologies: “My first book was published by something called the McGill University Press, but there was no such thing as McGill University Press. A professor of poetry and myself decided to start the McGill poetry series and we got a few subscriptions together, enough to pay for the printing, and we sold them around the campus. ... It was an extremely modest operation, by any standards, but we thought it was wonderful. That's what we thought a writer's life involved.”

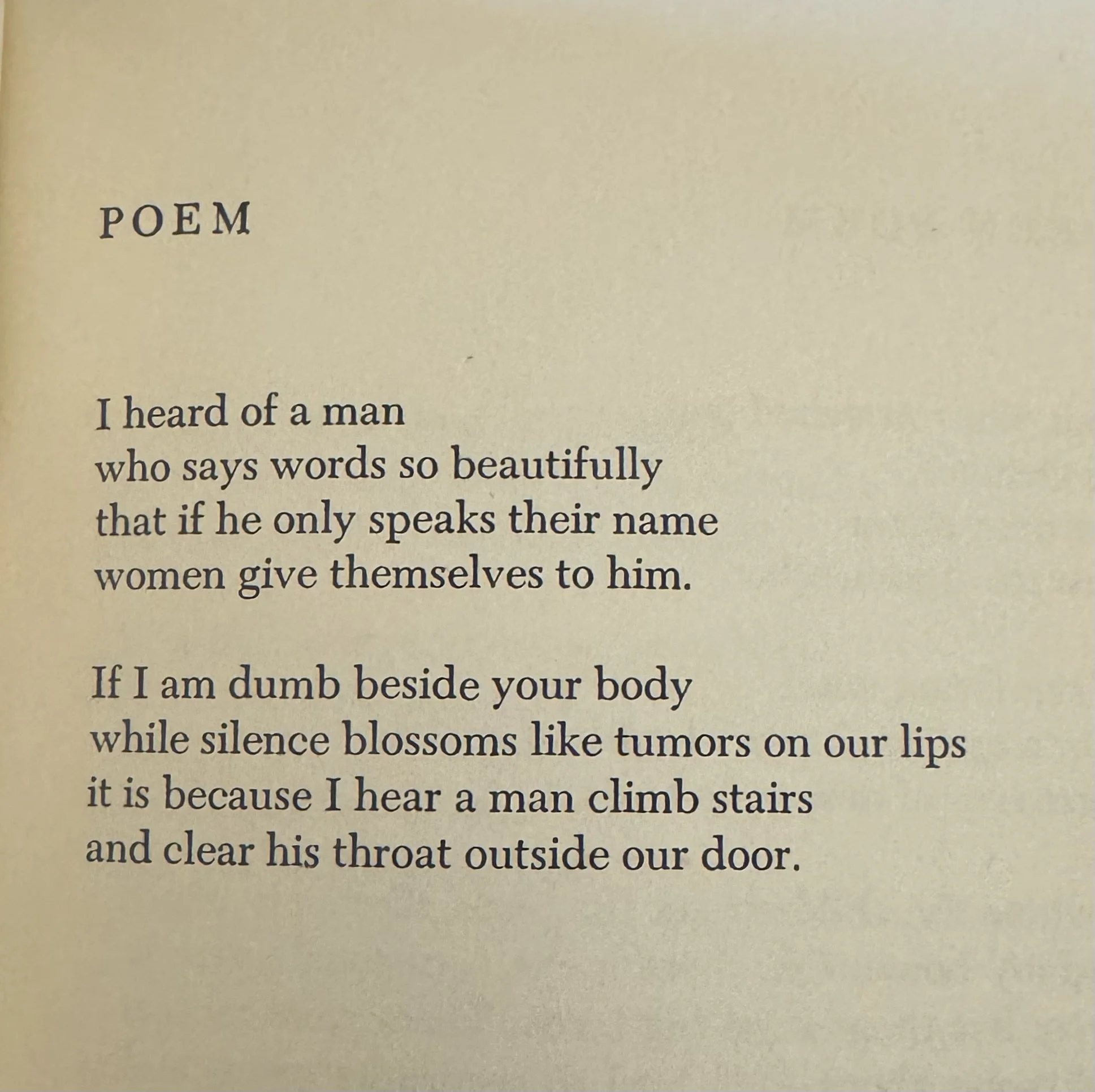

Cohen’s debut book of poems, Let Us Compare Mythologies, was dropped onto the Canadian literature scene by a 22-year-old who would go on to become one of the most revered, renowned artists in history. And while the work itself may not hold against the depth and reach of his more mature collections, the themes he explored planted seeds for what would become major aspects of his literary identity—god and sex. These poems brim with references, ranging from biblical and Homeric to Eastern mystical and classical, and are drenched in a sort of intellectual cynicism. Written between the ages of 15 and 20, these poems provide insight into Cohen’s early approach to poetry which changed drastically over the years. Here’s my favorite poem from the collection—prepare for chills!

11. Parasites of Heaven (1966)

Leonard Cohen referring to Parasites of Heaven: “I’ve got a new book of poems ready to go out…but I don’t want to be glutting the market with my work so I’m holding that back a while.”

Among the most widely referenced tracks in Cohen’s triumphant discography are songs whose lyrics originated in poems from Parasites of Heaven. This collection of poems was published prior to his transition into the music industry as a singer-songwriter, only a year before the release of his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, and the reader feels a transition in vocabulary from poem to song. Parasites of Heaven contains our first glimpses of songs that would later become “Suzanne,” “The Stranger Song,” and “Avalanche” and is often regarded as a partner-read to Beautiful Losers. It’s less representative of his overall body of work. The book was written in large part during Cohen’s final years in Hydra (Greece), offering some insight into his lifestyle and thought processes during those career-defining years. Among the many memorable poems, here’s one:

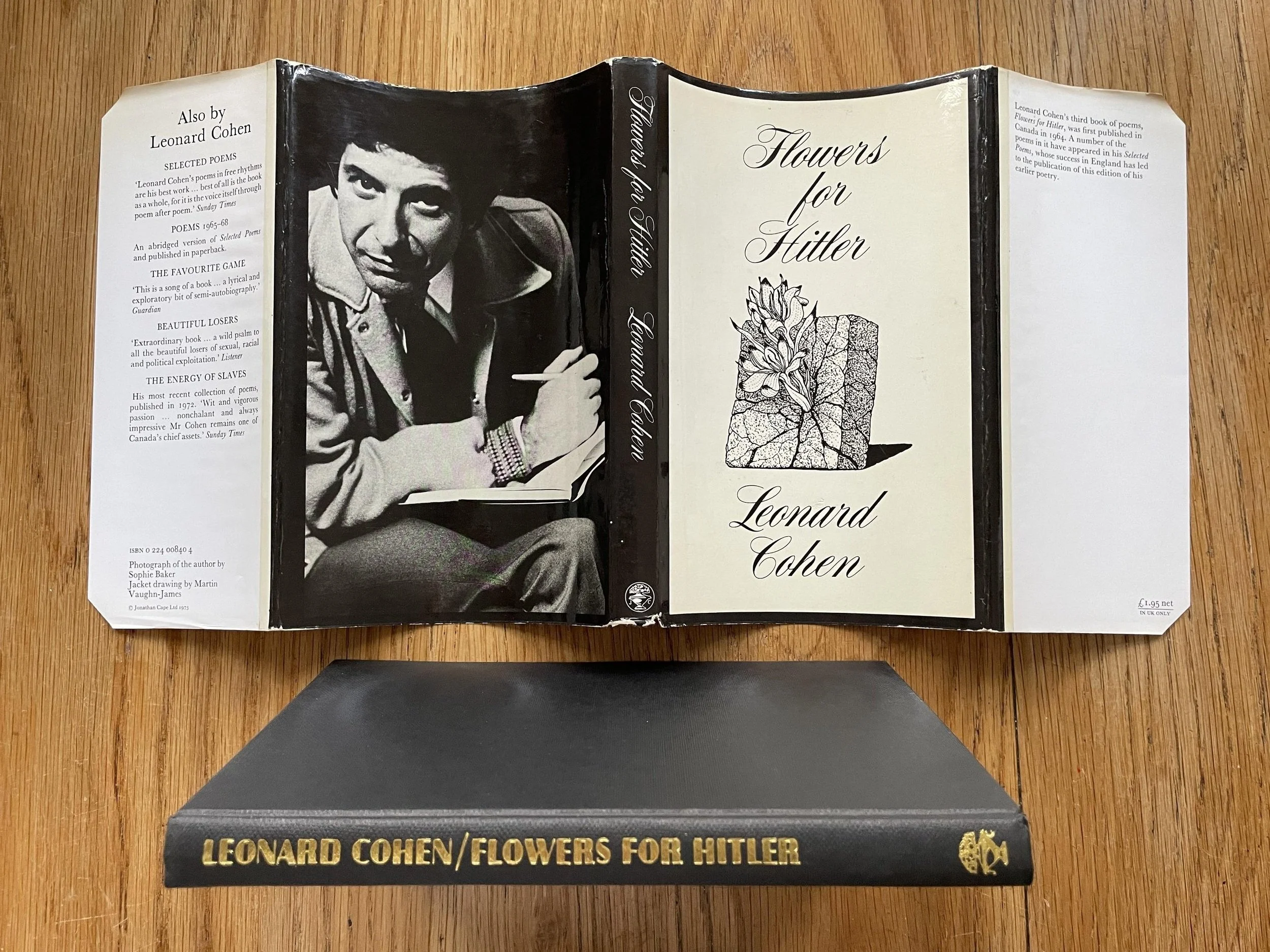

10. Flowers for Hitler (1964)

Leonard Cohen on Flowers for Hitler: “What point is there to a political solution if in the homes these tortures and mutilations continue? That’s what Flowers for Hitler is all about. It’s taking the mythology of the concentration camps and bringing it into the living room and saying, “This is what we do to each other.” We outlaw genocide and concentration camps and gas and that, but if a man leaves his wife or they are cruel to each other, then that cruelty is going to find a manifestation if he has a political capacity and he has. There’s no point in refusing to acknowledge the wrathful deities. That’s like putting pants on the legs of pianos like the Victorians did. The fact is that we all succumb to lustful thoughts, to evil thoughts, to thoughts of torture.”

I love that book title so much! This is Cohen’s third poetry collection, but the first to include the sketches and drawings that people loved and grew to expect from him. It is also unique in its marking of Cohen’s departure from largely religious imagery and hieratic language to focus more on man’s dark and evil tendencies. The topical focus on Holocaust is an element of his commentary on society and morality, but does not monopolize the book’s theme as much as it utilizes its intensity as an operative example. Here, Cohen invites us to witness the impact of such man-made horrors, extrapolating perceived truths and limitations of mankind, and attempts to locate the source of human cruelty. We soon find that one dark theme is abandoned and overturned by the next. Calling forth a figure like Hitler to ripple under the surface of these poems is an audacious choice on Cohen’s part. It is in this collection that he really embraces the darkness that he perfected by Songs of Love and Hate.

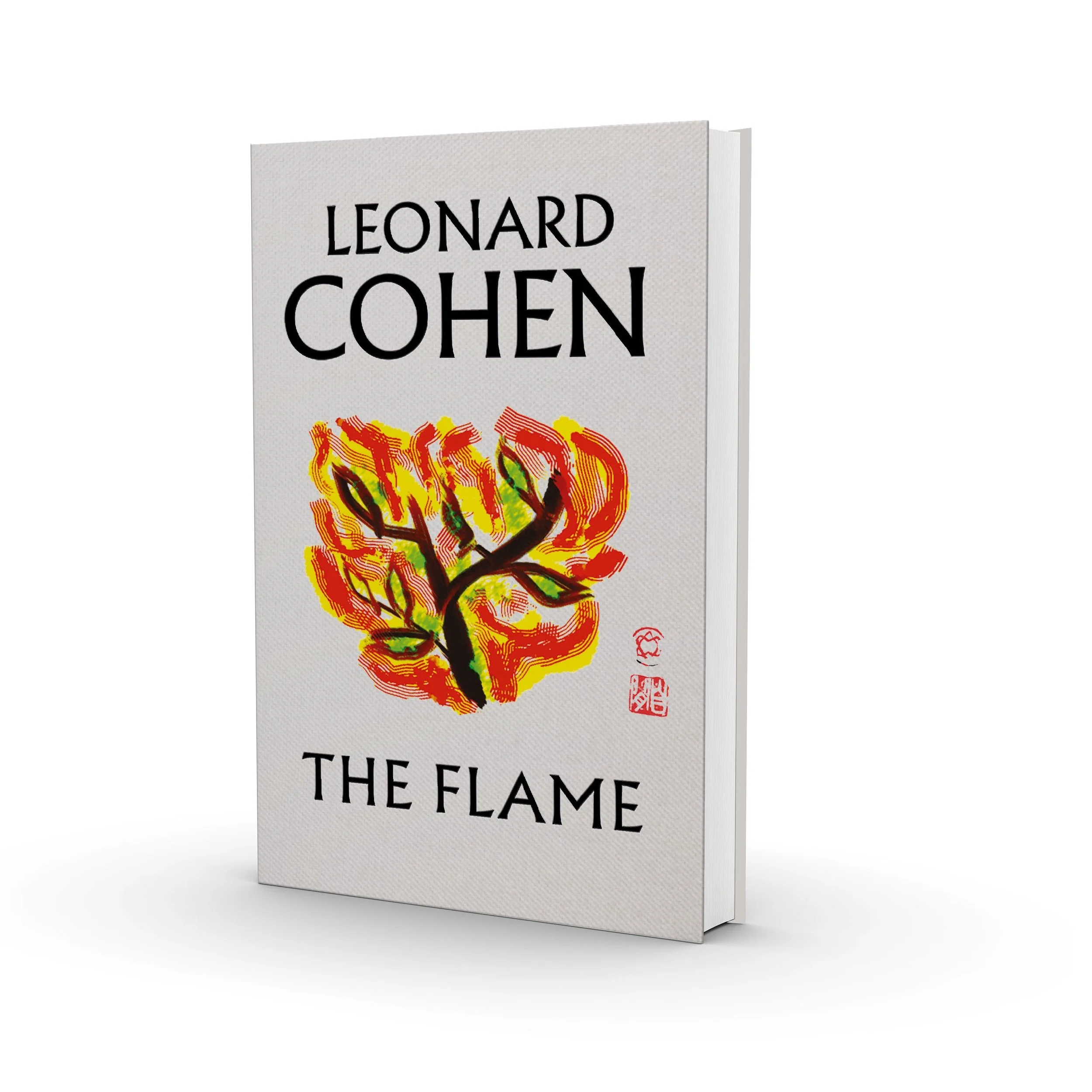

9. The Flame (2018)

Adam Cohen in his Foreword to The Flame:

This volume contains my father's final efforts as a poet. I wish he had seen it to completion—not because it would have been a better book in his hands, more realized and more generous and more shapely, or because it would have more closely resembled him and the form he had in mind for this offering to his readers, but because it was what he was staying alive to do, his sole breathing purpose at the end. In the difficult period in which he was composing it, he would send "do not disturb" e-mails to the few of us who would regularly drop by. He renewed his commitment to rigorous meditation so as to focus his mind through the acute pain of multiple compression fractures and the weakening of his body. He often remarked to me that, through all the strategies of art and living that he had employed during his rich and complicated life, he wished that he had more completely stayed steadfast to the recognition that writing was his only solace, his truest purpose.

Published in 2018 two years after his passing, pieces featured in The Flame allow Cohen’s lovers a glimpse of his final creative moments. The book was finalized and titled by his son, Adam Cohen, who referenced the imagery and symbolism of flames as his father’s commitment to bolder, riskier conversations throughout his lifetime as an artist. Some regard the book as being more unfiltered and raw than others, and nearly confessional in Cohen’s golden years, as he settled deeper into the rhythmic sound and contemplative acceptance that he had carefully constructed for the duration of his professional life. This book also contains lyrics from his last three albums, with songs like “Samson in New Orleans,” “Almost Like the Blues” and his final hit, “You Want it Darker.” The great humor Leonard possessed throughout his life is modern and quick in The Flame, and again we laugh at the mental image of Cohen, the great folk revivalist, penning poems like “Kanye West is Not Picasso” — it’s one of my most favorite poems of all time! The Flame is a “final testament” to the poetic heart of Leonard Cohen, riddled with drawings and photographs of his notebooks, we witness a busy mind with no shortage of things to say. It also contains a few letters that make the book a beloved work.

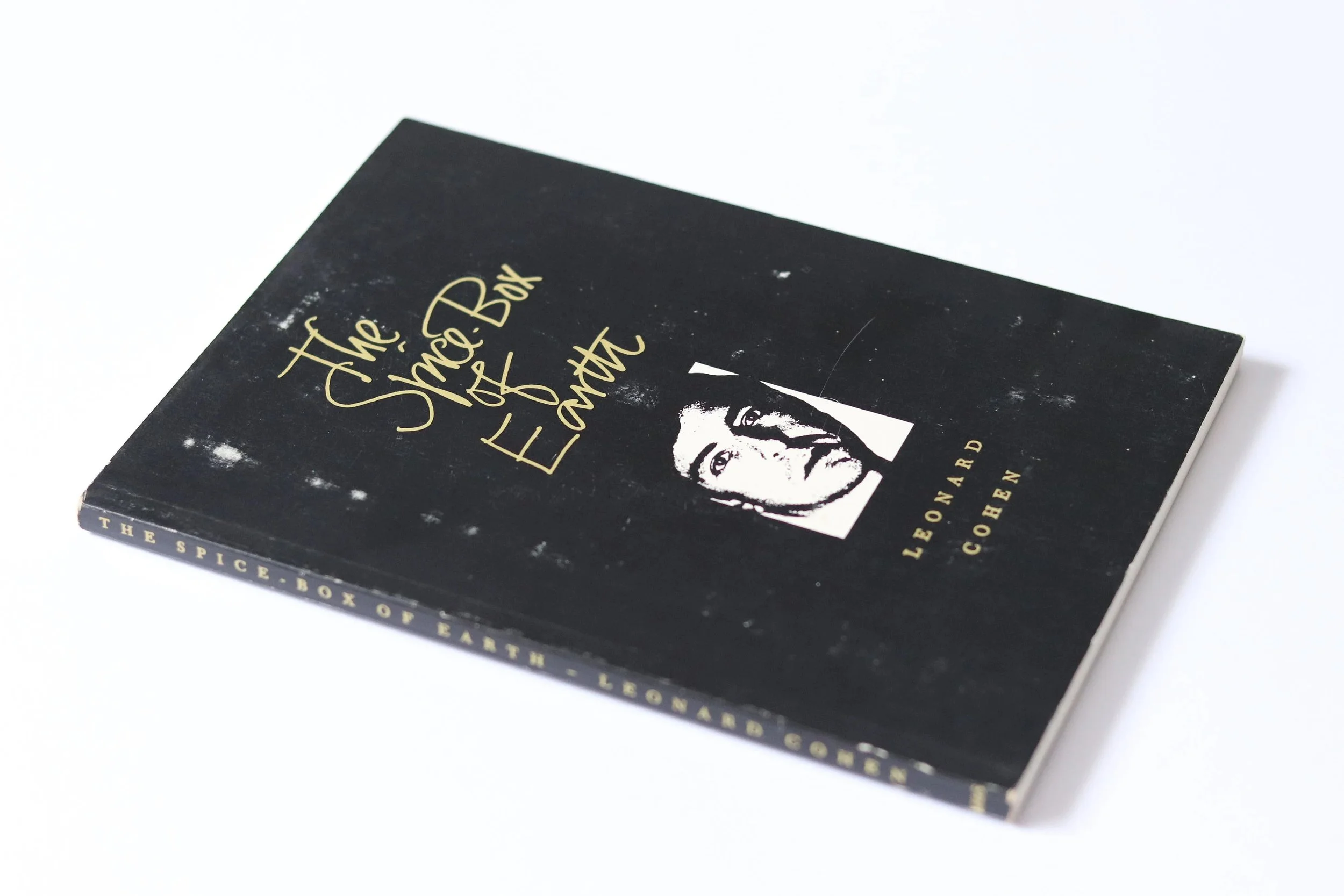

8. The Spice-Box of Earth (1961)

Leonard Cohen on The Spice-Box of Earth: “I wouldn't like to see these poems rendered in any sort of delicate print. They should be large and black on the page. They should look as if they are meant to be chanted aloud, which is exactly why I wrote them.”

By the early 1960’s Cohen had begun to solidify his place on the podium with The Spice-Box of Earth, forging his reputation for poems as explorative tools regarding life’s unending intersections of faith, sexuality, history and interpersonal relationships. Cohen takes several opportunities throughout the collection to impart the speaker’s own opinion or perspective straight to the page with bold and definitive proclamations. This is balanced by the sense of wonder, curiosity, and open-endedness that characterizes a younger Cohen, distinct from the more solidified rhetoric in his old age. Spice-Box has some of my most favorite LC poems: “For Anne,” “Dead Song,” “Gift,” “As Mist Leaves No Scar,” “Lines from My Grandfather’s Journals,” “Twelve O’Clock Chant,” — poems that were often read or sung by him in concerts. Here’s one poem that I wish I’d written, possibly my most favorite LC poem of all time: Beneath My Hands. And here’s another:

7. A Ballet of Lepers: A Novel and Stories (2022)

Leonard Cohen on being a novelist:

“What we call a novel, that is, a book of prose where there are characters and developments and changes and situations, that’s always attracted me, because in a sense it is the heavyweight arena. I like it—it frightens me, from that point of view—because of the regime that is involved in novel writing. I can’t be on the move. It needs a desk, it needs a room and a typewriter, a regime. And I like that very much.”

Another posthumous publication (one hopes for many more to come), Ballet of Lepers exemplifies Cohen’s ability to work outside of himself. It contains a variety of short stories surrounding distinctively troubling plotlines and personas, alongside the eponymous novel (chronologically his first novel). Cohen spared no creature comforts as he delved into uneasy and controversial subject matters in great detail, teetering on a line between shocking and transformative—that is, if readers make it to the “other side.” The diverse set of perspectives from the novella and short stories, many that do not pertain to his lived experiences, can be interpreted as probationary and speculative about the world of character-writing he would continue to develop in later years. Cohen, the novelist, proves to be immeasurably bright, leaving us giggling to ourselves while grappling with grave themes of loneliness and lovelessness. “The Shaving Ritual,” one of his most hilarious stories, is devoted to an American couple called the Eumers—“rhymes with tumor,” we’re reminded multiple times, who are unable to communicate their love. In “Saint Jig,” devoted friend Henry secretly hires a sex worker for Jig who struggles with dating due to a deformity in his hand, who fails to consummate anything. Love and despair are always around the corner from each other in these stories about different kinds of failure.

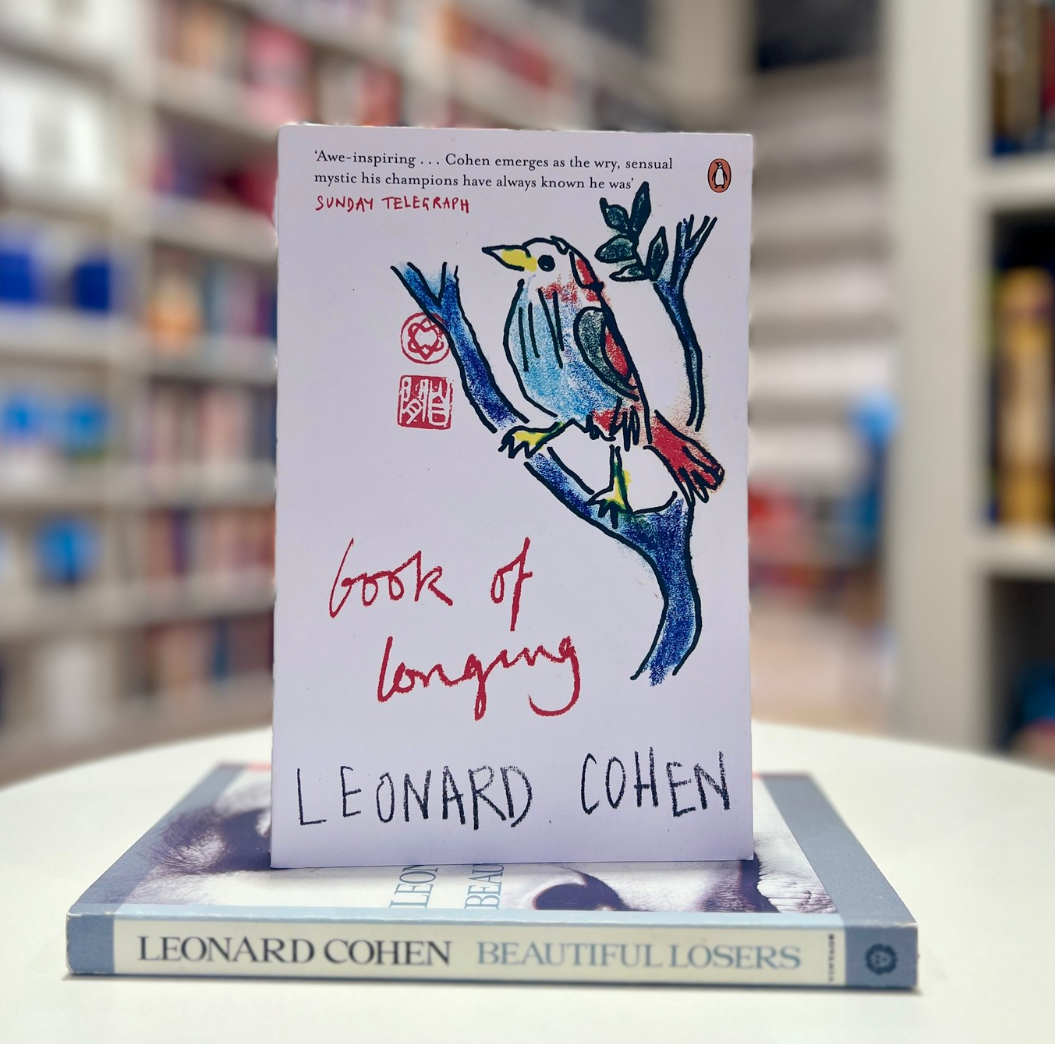

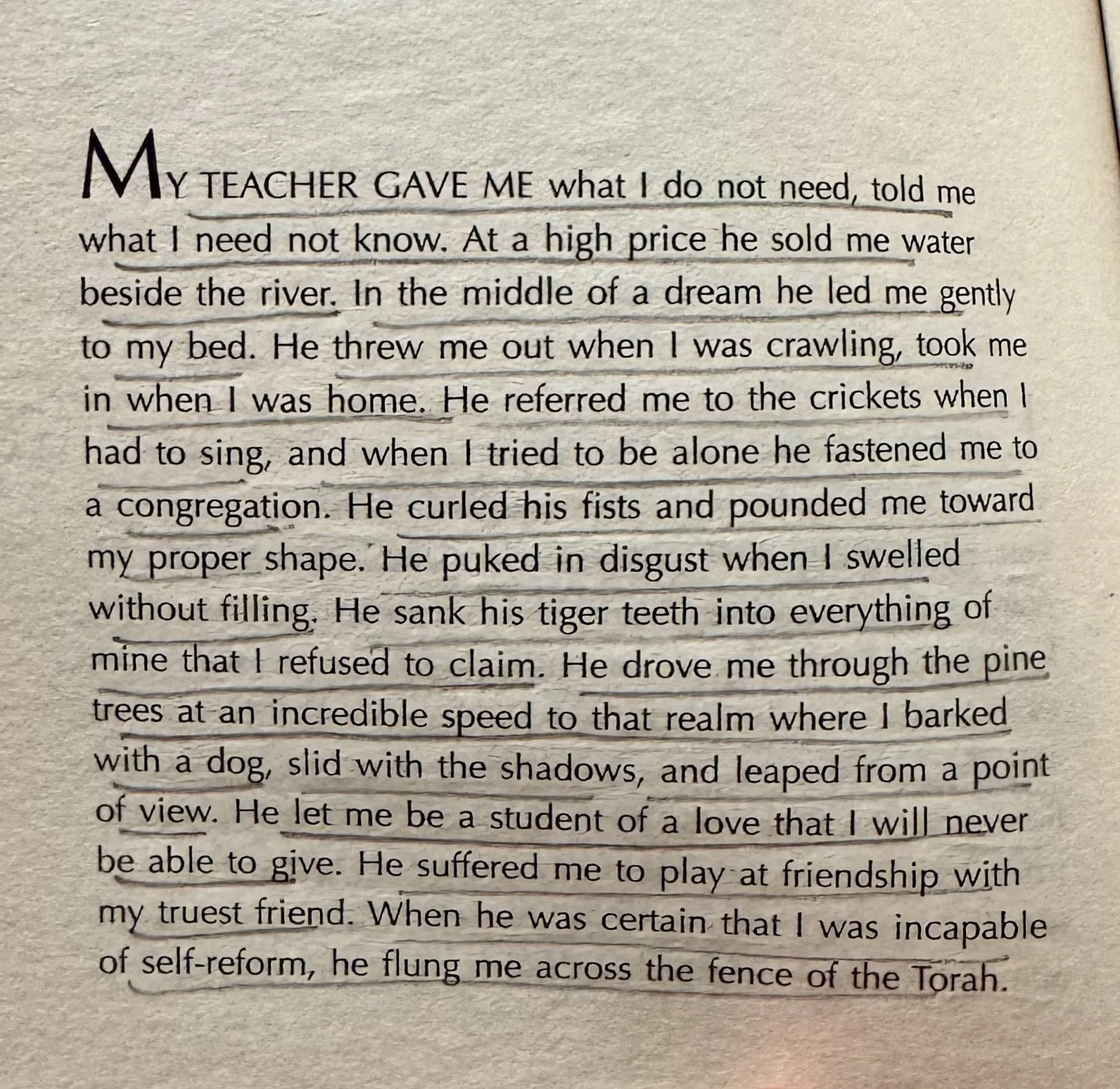

6. Book of Longing (2006)

Leonard Cohen on Book of Longing: “Well, a lot of that book, the Book of Longing, is a kind of sendup of the monks’ life, an ironic reflection on the religious vocation.”

Philip Glass turned Book of Longing into a “Song Cycle”: “Leonard and I first began talking about a poetry and music collaboration more than six years ago. We met at that time in Los Angeles, and he had with him a manuscript…In the course of an afternoon that stretched into the evening, he read virtually the whole book to me. I found the work intensely beautiful, personal, and inspiring. On the spot, I proposed an evening-length work of poetry, music, and images based on this work. Leonard liked my idea, and we agreed to begin. Now, six years later, our stars are in alignment, the book is published, and I have composed the music.”

An illustrative and reflective masterpiece, Book of Longing is a stark example of the aforementioned “old age” serenity we see from Cohen’s later works, peppered with some humor and sex. This is where we see most strongly a sense of stability, “zen,” and playfulness to his rhythmic verse punctuated with a few prose poems. He wrote most of Book of Longing while living in a monastery in Los Angeles and then some in Mumbai, in a period where Cohen’s lifelong depression began to lift. Chock-full of dirty jokes and doodles of naked women, Cohen tells us what it is like to age while retaining the libido of his youth. “Early Morning at Mt. Baldy” is one that sticks out among the tongue-in-cheek pieces, describing Cohen’s dressing routine as a monk. He describes each layer of clothing meticulously, “which I put on quickly… / over my enormous hard-on.” Book of Longing is dedicated to Irving Layton, Leonard’s early mentor and lifelong friend. Above all this book is reverent, Cohen bows his head to his teachers time and time again. Owing to their perfect rhythm and meter, many pieces from this collection appeared on his later albums.

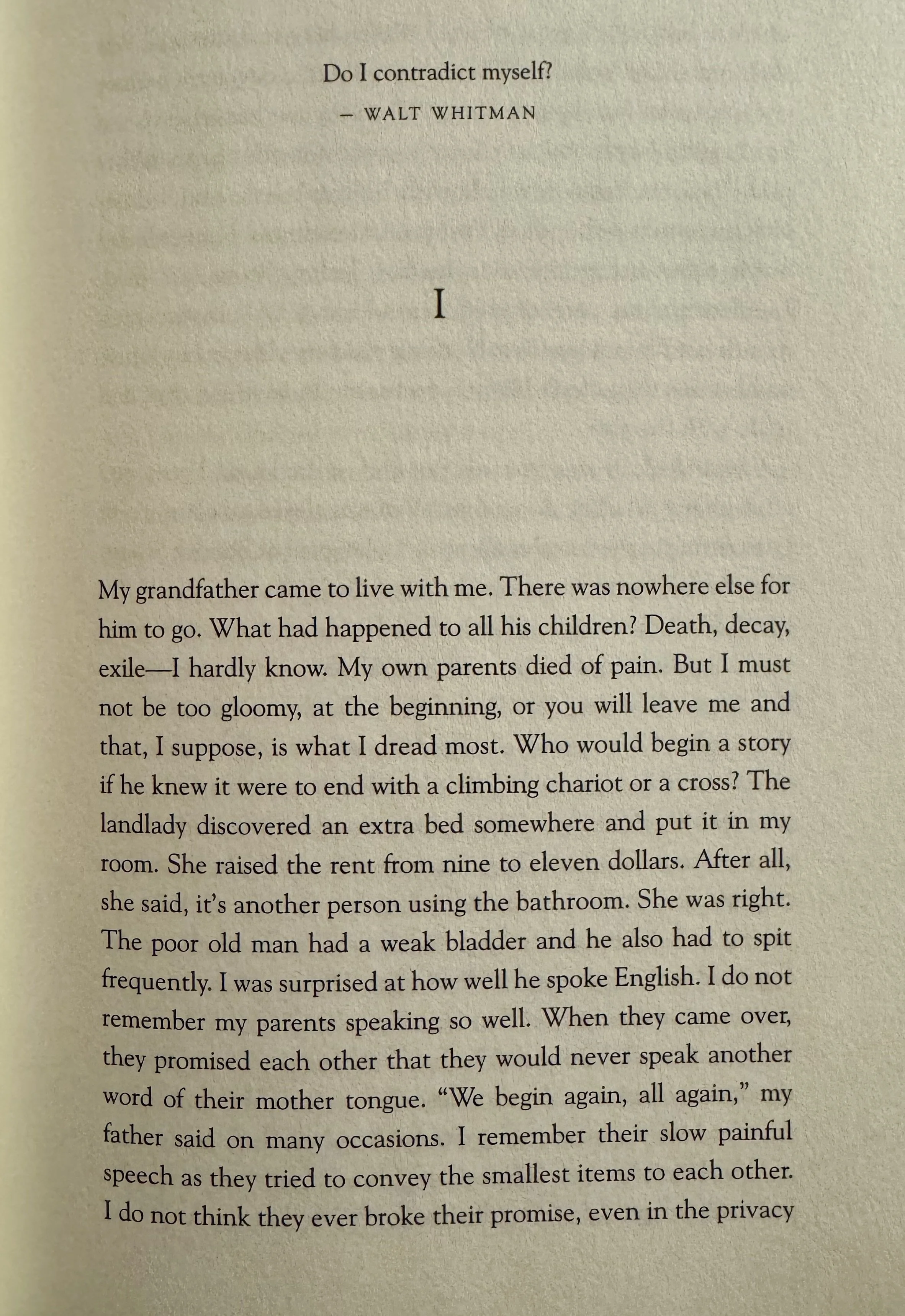

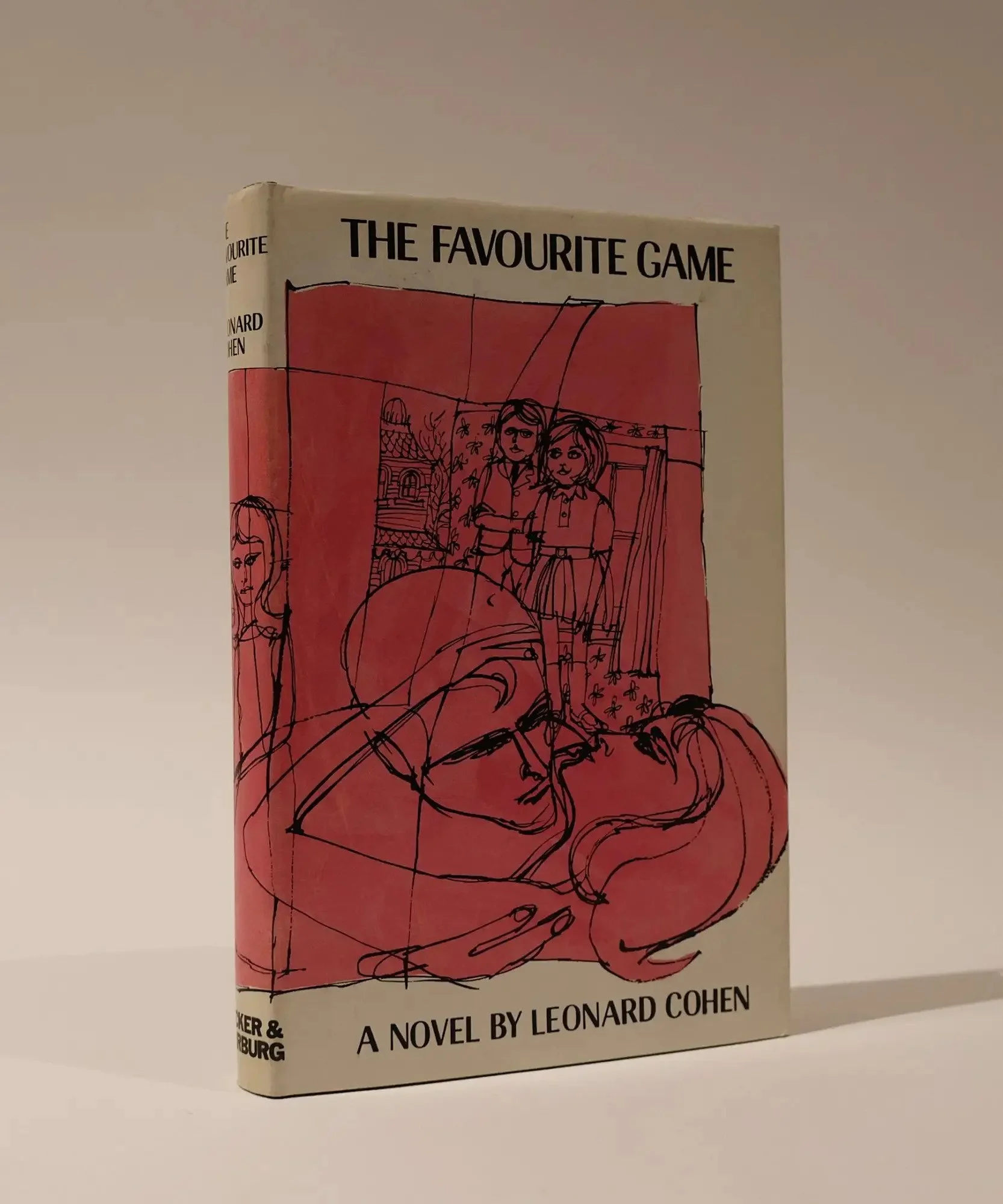

5. The Favourite Game (1963)

Leonard Cohen on The Favourite Game: “People have ways of revealing themselves to one another. Sexuality is one way but it is not the exclusive way. Maybe in The Favourite Game, being an extremely randy young man, I played the whole hand on that particular card, but I don't feel that way now.” Asked whether he was preoccupied with sex, he said, “A man’s a fool if he isn’t. But I didn’t write this thing to titillate, although if it does titillate, it’s an extra bonus.”

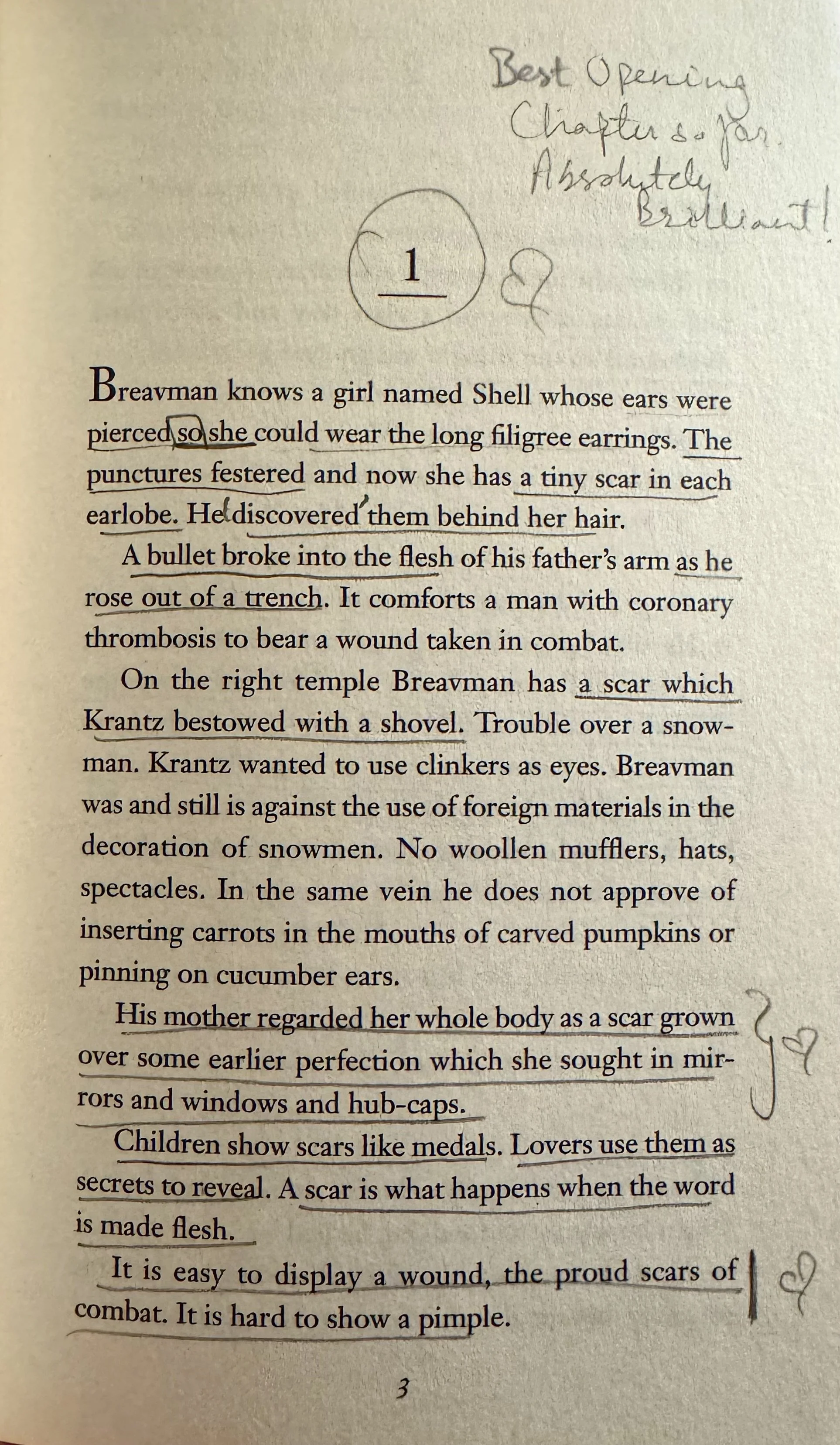

Upon release, controversy surrounded The Favourite Game, Cohen’s debut novel. Written while he was supported by a Canada Council grant in the early 1960s, the book marks one of Cohen’s earliest demonstrations of romantic and sexual themes threaded through a body of work, rooting itself in vibrant desire. Cohen shows us the struggle of a young writer’s experimental nature, juxtaposing explicit motivations, acceptance, identity, and questions of shame.

Many suspect The Favourite Game of being highly autobiographical, the main character Lawrence Breavmen sharing so many aspects of life with the author — their Jewish heritage, childhoods passed by in the idyllic upper-class neighborhood of Westmount, adolescence spent in the lively city streets of Montreal, even the death of Cohen’s father is mirrored in Breavmen, whose last name is an obvious play on the word bereavement. However, Cohen stated in a CBC special that while the emotions he writes of cannot be anything but autobiographical, the incidents and folks between the pages are entirely made up. In this same interview, a young and arrogant Leonard Cohen bats away the reviewers’ idea of having to get one’s first novel “out of the way” before they can go on to write anything of importance. The Favourite Game has an unforgettable first page:

4. The Energy of Slaves (1972)

Leonard Cohen on The Energy of Slaves: “I’ve just written a book called The Energy of Slaves, and in there I say that I’m in pain. I don’t say it in those words because I don’t like those words. They don’t represent the real situation. It took eighty poems to represent the situation of where I am right now. That to me totally acquits me of any responsibility I have of keeping a record public. I put it in the book. It’s carefully worked on. It’s taken many years to write and it’s there. It’ll be between hard covers and it’ll be there for as long as people want to keep it in circulation. It’s careful and controlled and it’s what we call art.”

This fifth collection of poems, published after three of his albums is, to date, Cohen’s most controversial collection of poems, both upon launching and by today’s standards of Cohen’s work. Described by a critic as “deliberately ugly, offensive, bitter, anti-romantic,” Cohen considered this dark and intense book a document of his struggle. Many felt it brought an uncontrolled disclosure of mental illness. Bracing, challenging, and equally beautiful and off-putting, as it says on the back-cover of the book, it remains one of his most compelling and complex works. It homes the poem our magazine is named after: The Only Poem. And here’s a short unforgettable poem that is the essence of Vedas and many religions.

3. Death of a Lady's Man (1978)

Leonard Cohen on Death of a Lady’s Man:

“I think I’ve exhausted the whole process of subject/object and seeing the world from that particular point of view for a little while. Death of a Lady’s Man is a closing statement on a certain chapter. I do have a feeling that I would like to write a book or even live a life where the I is not so prevalent…I think that the only way out of suffering is to somewhat dissolve or attack that particular point of view.”

Following the 1977 release of his album Death of a Ladies’ Man, Cohen published his ninth book Death of a Lady’s Man the next year. These titles alone give us a picture of Cohen, half womanizer, half womanized depending on the punctuation. Death of a Lady’s Man follows the destruction of a marriage, and a fight with the spirit; it remains a captivating spearhead for what was arguably the writer’s literary prime. In Death of a Lady’s Man Cohen follows each title with commentary with the same title, remarking on, adding to, explaining, or denouncing the piece respectively. A destructive, angry, vulgar Cohen emerges off the page, tirades against his wife and the perfect strangers he took to bed to rebel against this union. Out of these flames, gentle poems from Cohen like “Slowly I Married Her” strike us: “And all through Death’s dream / I move with her lips / The dream is a night / but eternal the kiss.”

Many reviewers have agreed on this book being representative of Cohen’s mastery of the craft, while softening his intensity with warmth, beauty, and effective personal insight. Although the bulk of this collection speaks to his romantic relationships, a nostalgia for the old places and friends is seen clearly as well. Heavy with sorrow, he begins to satiate the growing darkness with religious placation (which subsequently becomes the heart of Book of Mercy). Both thoughtful and thought-provoking, the collection manages to be broad but cohesive, decorative yet emotionally moving.

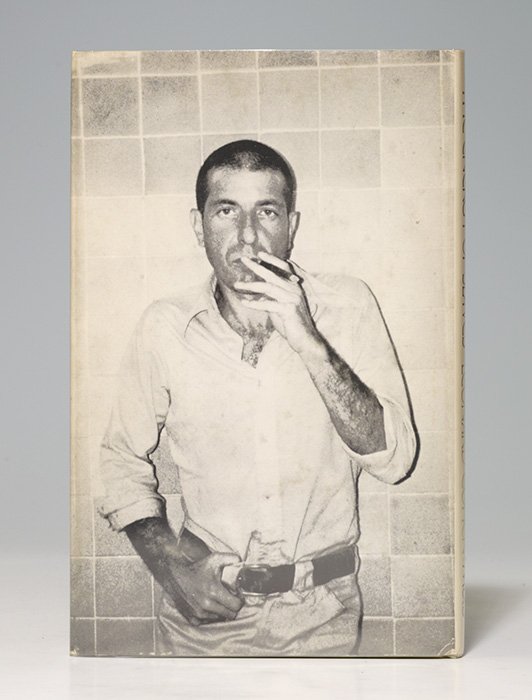

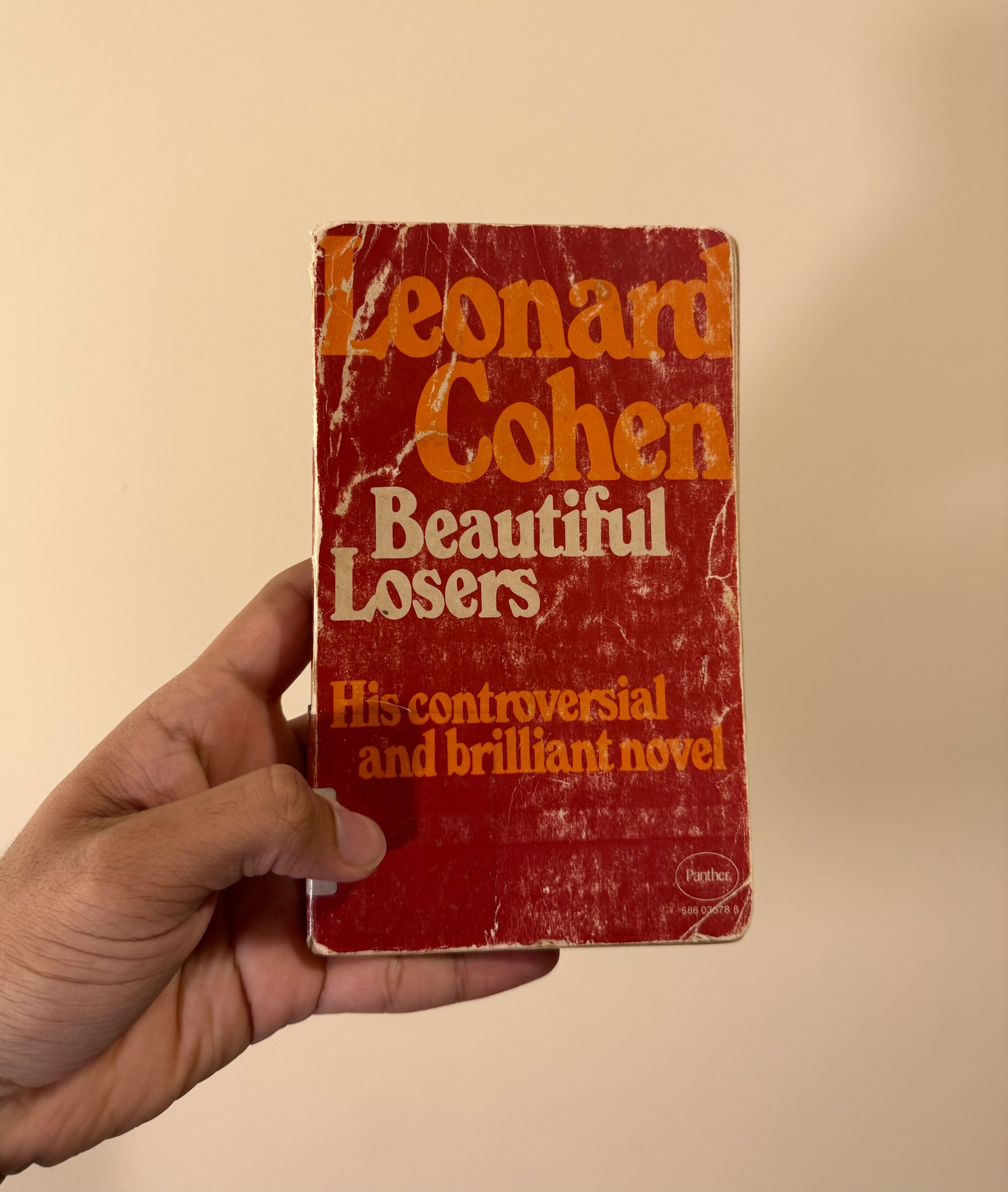

2. Beautiful Losers (1966)

Leonard Cohen on Beautiful Losers:

“I wrote Beautiful Losers on Hydra, when I’d thought of myself as a loser. I was wiped out. I didn’t like my life. I vowed I would just fill the pages with black or kill myself. After the book was over, I fasted for ten days and flipped out completely. It was my wildest trip. I hallucinated for a week. They took me to a hospital on Hydra. One afternoon the whole sky was black with storks. They alighted on all the churches and left in the morning. And I was better. Then I decided to go to Nashville and become a songwriter.”

His second novel, known for its avant-garde style, Beautiful Losers, Cohen’s second and final novel from 1966, earned its reputation as indistinguishable from the age of free love and flower power. Beautiful Losers was born from an amphetamine-and-sandwich-fueled marathon on the terrace of his home in Hydra, Greece, served up by his devoted muse, Marianne. Deeply controversial and political, the book is emblematic of the countercultural shifts sweeping through North America at the time, with some reviewers going as far as condemning the work as “verbal masturbation” for its excessive use of hyper-sexual scenarios, radical narrative and enigmatic spiritual invention. Some stream-of-consciousness moments leave us dizzy with incredibly rich demonstrations of language.

Only Leonard Cohen could come up with a book like Beautiful Losers. It follows an unnamed man who pledges his devotion to a 17th-century Mohawk saint, Kateri, or Catherine, Tekakwitha. The narrator divides his attention between fantasies of Tekakwitha’s life, and memories of his wife, Edith, and best friend, F. Edith, F, and the narrator are entangled in a bizarre triangle, all three of them are romantically involved with the other, the men are forced to confront this liaison after Edith’s suicide. Beautiful Losers is fearless in its depiction of sex, especially homosexuality, and the controversial Canadian separatist movement. While some felt it overly complex and radical, others (like us) have found much comfort and intrigue in Cohen’s decadent indulgence. The famous and incomparable “God is Alive, Magic is Afoot” is excerpted from this novel.

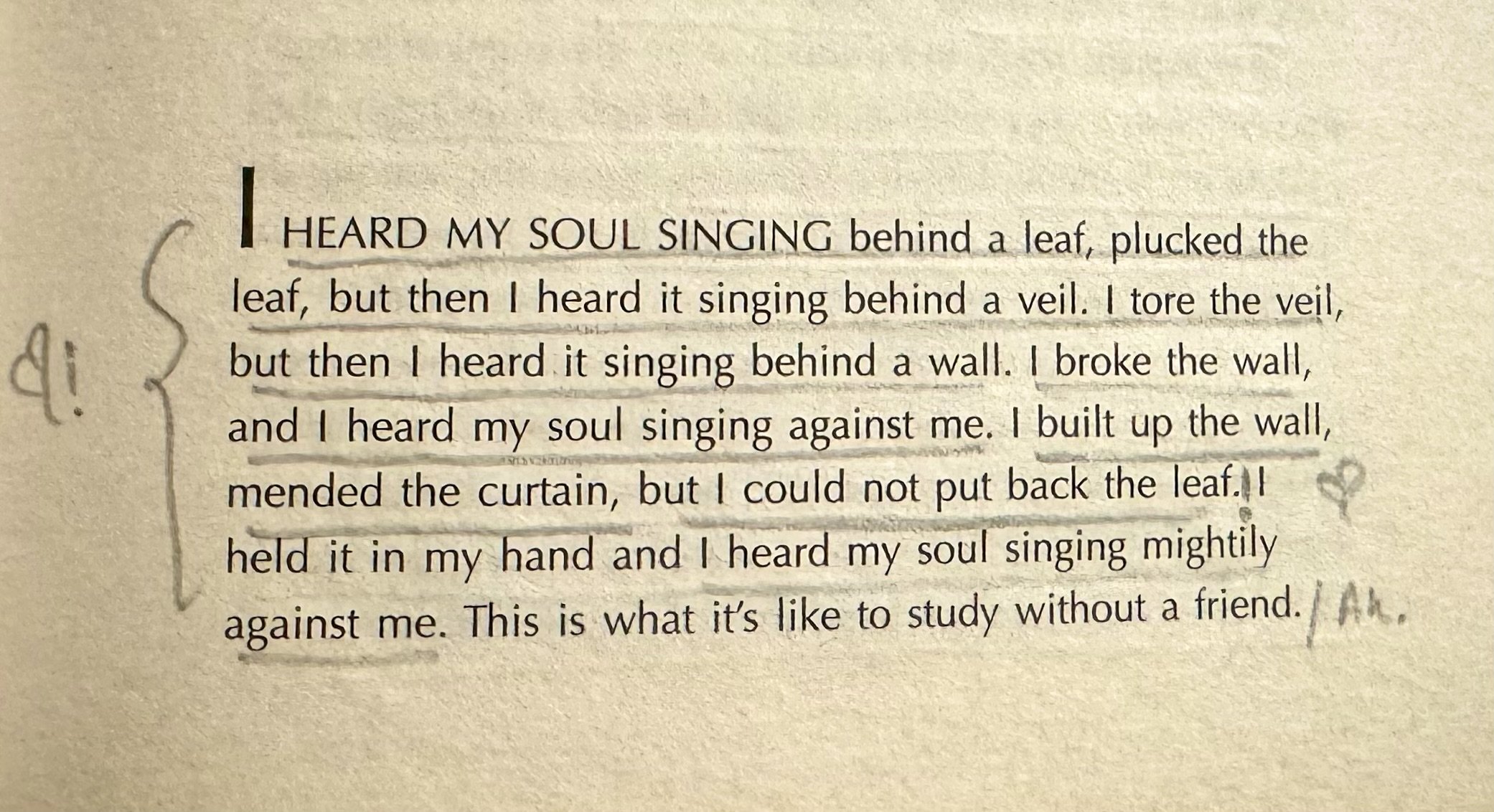

1. Book of Mercy (1984)

Leonard Cohen on Book of Mercy: “This is the kind of expression comes out of a situation where the health and welfare of the body & the spirit are deeply threatened, and that is when you see the world and you see the brute laws of necessity which govern the world and…as soon as you see that, your soul, as Simon Weil says, becomes “glued to prayer” and you realize the only way that you can reconcile this butcher shop of history, this veil of suffering is to glue your soul to prayer…[This book] verifies a certain kind of promise each of us has dimly heard, that there is a source of healing, that there is a torrent of mercy and that it operates in mysterious ways, and that it’s not always available, but with appeal it can be located.”

Leonard Cohen’s deep devotional capacity and long-standing knowledge of Jewish tradition comes through best in Book of Mercy as he offers prayer after prayer in short prose blocks. A collection of psalm-like prose poems reflecting his spirituality, each piece is assigned a number as opposed to a title, leaving the intent of the written lines to communicate for themselves, devoid of any outright assumption. We’re invited into the poem to uncover our own end-point, often hope and surrender. Cohen reinforces the ability he proved time and time again to present a soul-crushing, heart-wrenching text that is boundless while being utterly intentional about what it seeks to accomplish.

This 1984 collection, leading to his album Various Positions that carries the song “Hallelujah”, softly equips its audience with moments of solemn respite and spiritual engagement. In the midst of a tumultuous separation from his “wife,” Suzanne Elrod, his children were moved to the south of France. Elrod refused to have Leonard on her property, preventing him from seeing his children. Cohen then bought a caravan to live at the end of the dirt road that led to her house. Every day the bus would take the children to and from school, Leonard would be there to greet them. In an interview, Adam Cohen recounted his father’s presence as pedagogical in this period: teaching them Hebrew, lighting candles, reading them the Bible. Book of Mercy was written in that caravan. A deep penance vibrates within its pages. These poem-prayers have saved me countless times, illuminating my way on many dark nights of the soul: “Let me raise the brokenness to you / to the world where the breaking is for love.” As Leonard would say, if you feel your soul unemployed in a deep sense, like I did, then this is the kind of book that brings light to the heart.

It is our great honor to award the