12 Fall Poetry Collections That Haunt

Passing through landscape, memory, familial loss, collective cultural loss, and myth

by Turi Sioson

Often the hallmark of a good poetry collection — or at least the way I measure it, words repeating in quiet moments and sticking to my consciousness — is how much its work stays with us, how long its lines continue to echo. There are certain sounds and shapes that a poem can take that guarantees attachment. With the coming of Halloween, a haunting seems inevitable. What better way to achieve this than through poetry?

In Jennifer Chang’s An Authentic Life, ancestry and patriarchy dissolve with rhythmic voice and reflection; in Darius Atefat-Peckham’s Book of Kin, heritage and tragedy find homes in memory rendered by breathtakingly tender language. Emily Jungmin Yoon’s Find Me As the Creature I Am reminds us of our wild roots, and Jenny George’s After Image presses the outline of a lost loved one hard into our imaginations.

This month’s new poetry spooks, possesses, and psychologically thrills in lyrical, intimate, and experimental ways, leading us through contemporary horrors, encounters with wild animals, and loss. Read below to get to know the best new books to add to your poetic library.

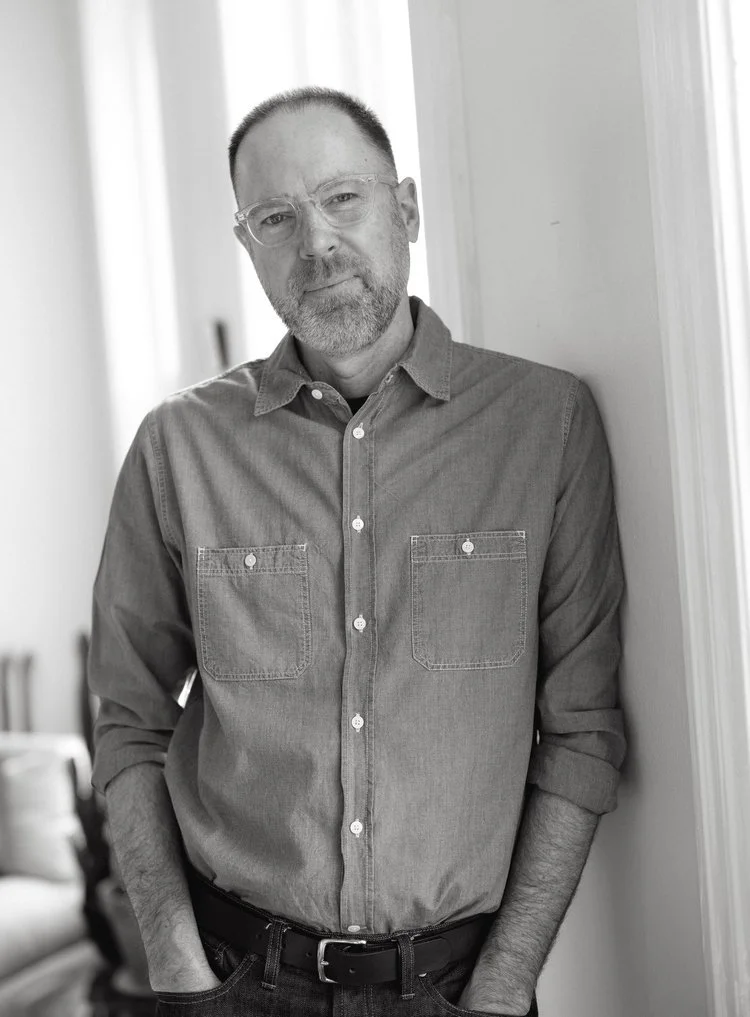

Hold Everything by Dobby Gibson

(Graywolf Press, 2024)

Wading through time, realism, and everyday demands, Dobby Gibson’s newest collection is crisp and delightfully strange, equally inviting and bewildering. More than an homage to language and those who wield it, Hold Everything illustrates a profound affection for life in all its complexities. “And half of me wonders whether it’s enough to be bewildered,” Gibson writes in “This Just In.”

With an eye honed for careful attention, Gibson renders a charming, hopeful picture of the everyday. Each line is its own world, a scene or image that can be attached or separated from the larger poem. “The answer to how much knowledge we should possess is / all we can bear,” he writes in “Sludge.” “As many ideas as we’re prepared to shock into life // and raise to live on their own.”

The collection’s titular poem is a stunning multi-page chronicle of all that we feel, carry, and experience. With equal parts childlike wonder and steady sensibility, Gibson urges us to not only survive but to carry the beauty and pleasures that cross our paths. While fiercely personal, Hold Everything makes you feel as though you’re sharing an experience. He echoes this in the collection’s final poem, “Say When”: “And when I say I, I mean you. And by you, / I mean we. Nothing singular and no reason why. / Every thought I’ve ever had about mountains, / my pockets full of infinity.”

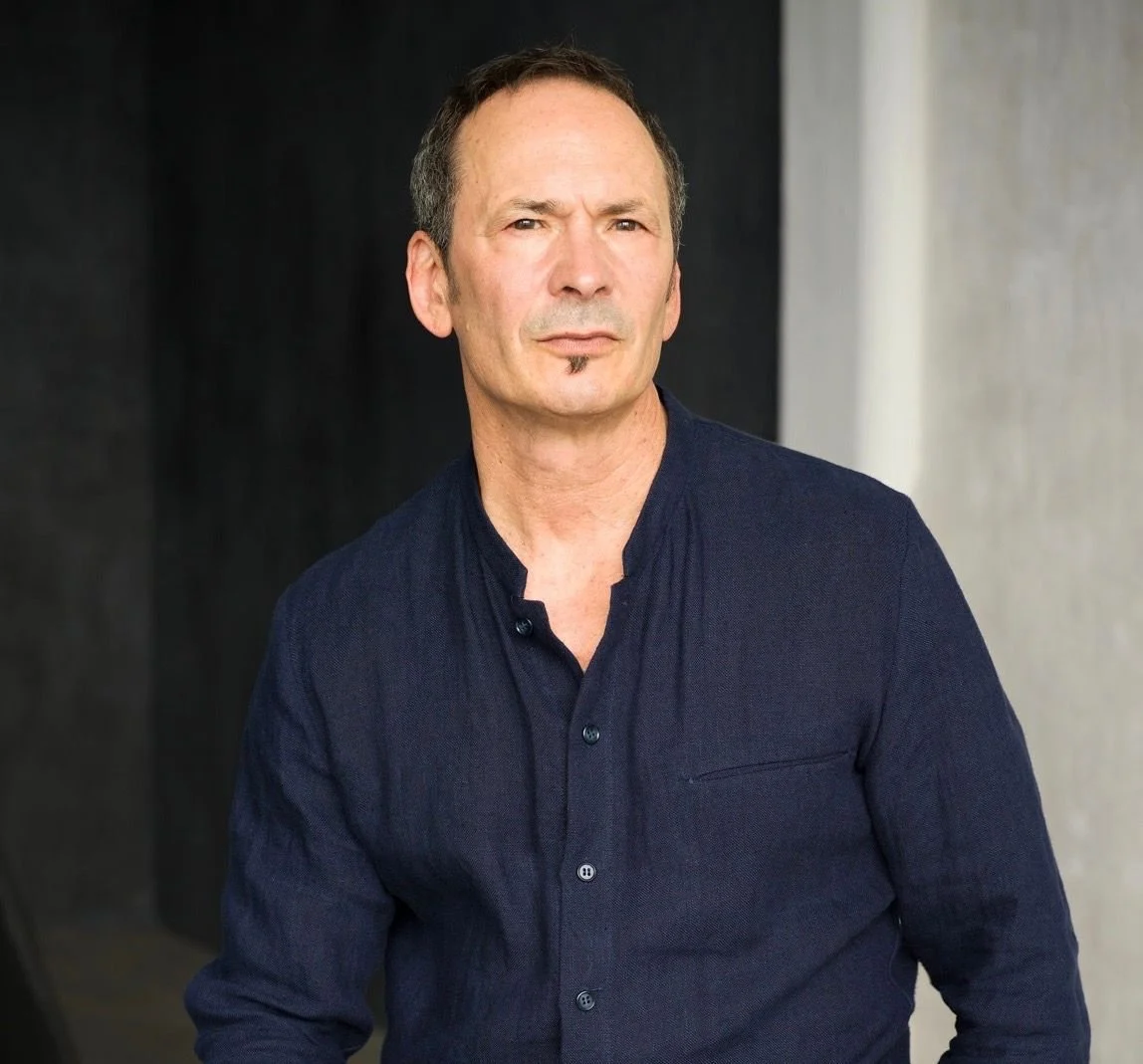

Mojave Ghost by Forrest Gander

(New Directions Publishing, 2024)

Driven by memory and informed by his “kaleidoscopic” sense of self, Forrest Gander’s Mojave Ghost reconciles the internal experience with physical movement across space. A novel-poem in which the past and present converge, the book is a lush landscape, tracing an emotional journey through Gander’s birthplace in the Mojave Desert to his current home in Northern California.

A coyote howls from Eden Isle, finding that “there’s no way / to mind the gap between first- and third- / person perspectives,” mirrored by Gander’s narrative explorations across the book. “Nor between the publicity of the world / and the self’s interiority. // Nor, for that matter, between past and present,” he writes. One one page he writes, “Happiness, she said once, is for amateurs”; on the next, bringing affecting intimacy to the page, he asks, “Will you let me / approach you? Bend forward / and touch consequence, tenderness, leave / the trace of my fingertips / on your throat’s dimple.”

An examination of self-identity is conducted through Gander’s poignant, ever-questioning voice into a desert mirage. “No matter how I tried, / I couldn’t shake the unreal out of me,” he writes. His depiction of landscape is equally muddled in a way that is wonderful, surprising, geological, and mystifying. Placed on its own page, centered among an expanse of white space: “There, where palms sway over a dry spring, / they come to encounter themselves / penetrated by birdsong, standing among trunks / and vines risen from the ground / like the births and messages they are.” Haunting and spiritual, Gander’s newest collection compels us to look at our connections to land and memory with tender, open eyes.

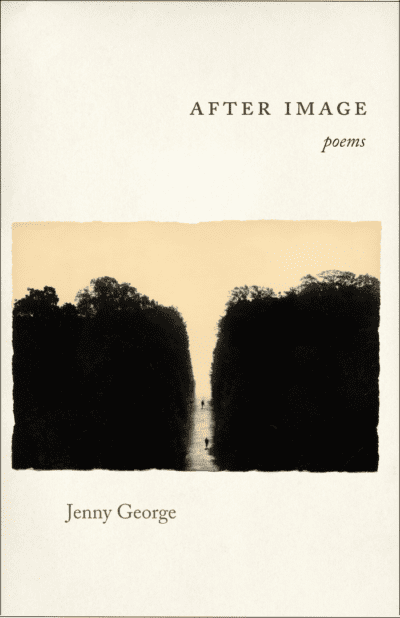

After Image by Jenny George

(Copper Canyon Press, 2024)

When entering Jenny George’s third collection, you’ll feel as though you’ve stepped into a still-life: “A table. And on it a vase / of flowering quince branches,” she writes in “Quantum.” After Image is surreal, unnerving, and filled with longing; it seems as though it’s missing movement, life. George’s poems serve as literal afterimages, an impression in the eye of something no longer there.

Her observations sometimes feel disconnected from the happenings within the poems and the grief present within the language. Her voice is blunt, matter-of-fact, which is perhaps what conveys the most feeling. “The trees are full of eyes. One body blots out / another body. Isn’t that how it works? / She died. It floats on my vision like a burn,” she writes in “Eclipse.” The poignancy of her images have the effect of a half-remembered dream — fragmented yet expansive, the inarticulable static blur of loss.

Central to the collection is also space: between the life the speaker shared with her beloved and the death that separated them physically. “In the kitchen, a bowl of mandarins / radiates emptiness,” she offers in “Interior (winter morning).” “Who were you / that even now the air’s disturbed?”

In After Image, grief is the “little cup of inverted / feeling // that begins in the dark // and on spring’s signal / climbs out— // as if the instructions are: / to articulate.” Something George achieves with bewitching mastery.

The Many Hundreds of the Scent by Shane McCrae

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024)

Last fall, Shane McCrae brought us his mythical, memory-laden collection in which absurd realities become soundscapes. Newly released in paperback, The Many Hundreds of the Scent traverses home, Homeric myth, injustice, and childhood; McCrae’s kidnapping as a child from his Black father by his white supremacist maternal grandparents holds particular weight across the collection.

“The silences of the dimmed house and the sounds / Of sleeping in it clashing, neither meshing with / The other, carry me to sleep. I am most with / My family then, each of us dreaming, each unknown,” he writes in “The Phantom Son,” embodying the waking dream–like quality that permeates each poem. Rhymes and lyrical turns of phrase and literal music sing throughout the collection: in “Hex,” “our breath / Escaping in the haze of its occasion, you / Watch yours disintegrate and do not recognize / Yourself.”

McCrae’s voice is enveloping and keen, punctuated by surprising line breaks and endings. In the titular poem he writes, “as / If scent, like touch, were place, a home not made / Of memories, but the next, searching inhalation / Always the next, with which the scent returns”; there is a reach for the past in his language. “The tower we have often built together / You from imagination, I from memory,” he adds, asserting that it is primarily through memory that he connects to this ghostly world.

“How / Far past the end of the old life is the end / Of living memory,” he wonders in “Far Past the End.” It’s a question that is not fully answered, yet the search is what highlights The Many Hundreds of the Scent’s affecting journey.

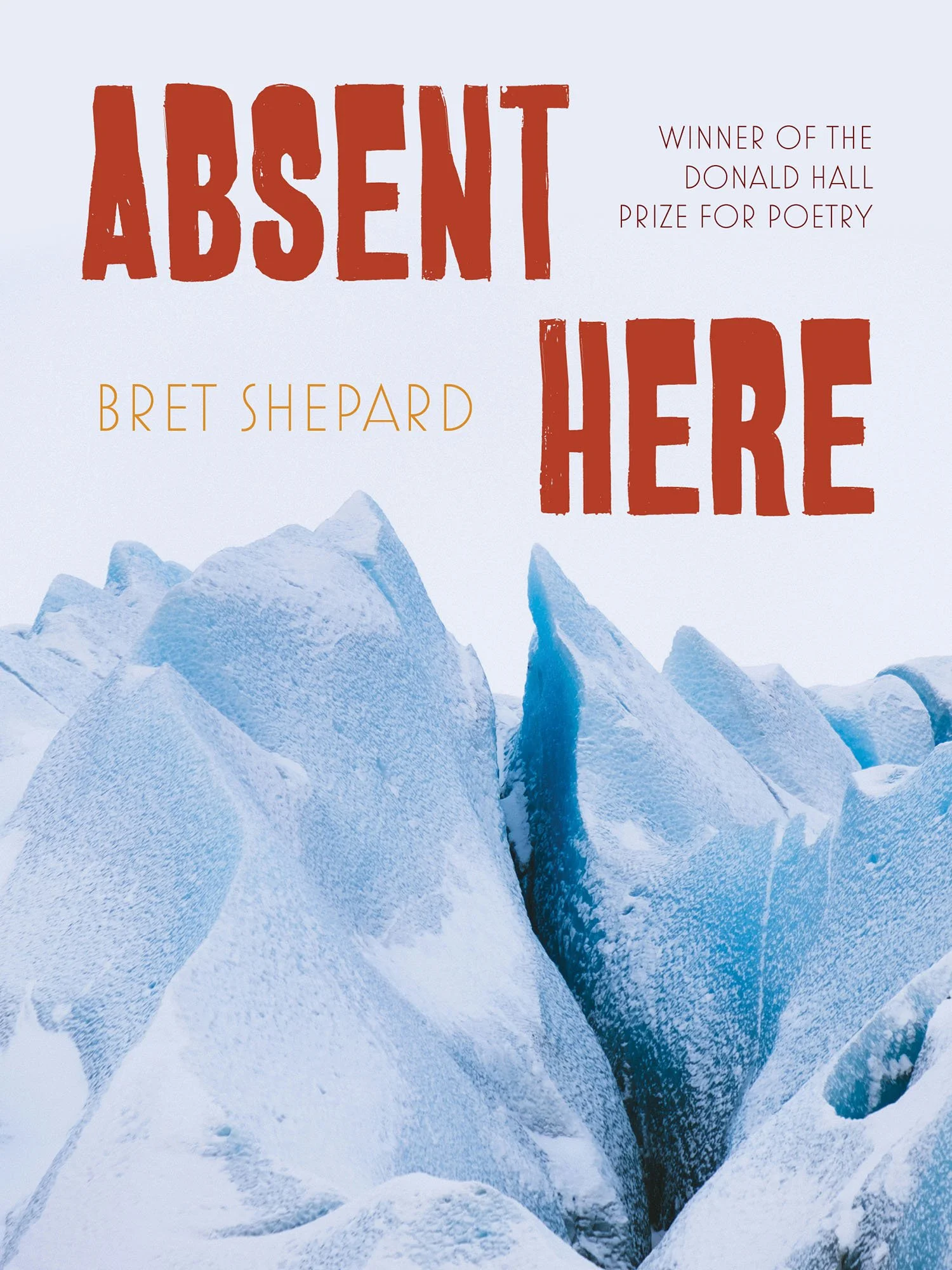

Absent Here by Bret Shepard

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024)

Vast and spacious, the arctic landscape within Bret Shepard’s newest collection, winner of AWP’s 2023 Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, possesses the page with lifelike particularity, even when what was disappears. “Absence is unresolved movement between two / events,” he muses in the first “Here but Elsewhere” poem. “What forms in absence of sight // is body felt.”

Reflecting on his childhood in the Alaskan North Slope, Absent Here is rich with community and nature, traversing the hardship and joys within both: in “On Ice,” the formation of ice “as simple // as holding each other through the night”; in “Last Sunset,” “dark / in many things is only one thing / desire hides inside itself.” Addressing poems to “we” and “you” extends a hand to us as readers, indirectly passing the lives, voices, and stories of the tundra onto our own memory.

Many poems are brief and yet these are among the most hard-hitting, producing scarcity and lonesomeness at the root of the collection. Memory, too, has a central place in the formation of these poems, creating “impossible versions.” In the third “Here but Elsewhere,” “Proof: my son tells me he saw my father / last night as he slept. He doesn’t know dream.” Language is voiced through what it is missing, intertwining ecology to gorgeous effect.

An Authentic Life by Jennifer Chang

(Copper Canyon Press, 2024)

Moving through family narratives, childhood memory, and collective hardship, Jennifer Chang’s third collection is lyrical and grounding. Chang’s contemplative voice is equal parts comforting and unsettling, forcing us to question along with her our beliefs and understanding of the world and our connection to identity.

“Meanwhile, every story is the same: // you run the books, you run your mouth, / you run the world,” she writes in “Pets,” interrogating familial expectations stemming from religion, ancestry, and the generational oppression of women. In the titular poem, knowing and not knowing converge, a sense that is felt across the collection: “I had not been taught to ask questions. / What is this. Who are you. Why. / I had not been taught to want.” In “Prodigal,” this idea wades into life independent from what the speaker once knew: “No one told me / I could survive // rootless, this / ceaseless wandering.”

The world of An Authentic Life is immersive and wide, traversing reflections on adolescence, philosophy, and literature, as Chang “[labors] over language / that in [her] head would not cohere.” In her luminescent images, there’s a personal closeness that links the speaker’s everyday with ours. Knowledge and awareness lend us power to realign ourselves and reconcile with loss.

“We marveled / how our words arrived wherever // we weren’t,” she remembers in “In the Middle of My Life,” capturing the feeling readers get while wading through Chang’s newest collection, a sense of wonder and sorrow for the things that exist both with and without us.

apparitions (nines) by Nat Raha

(Nightboat Books, 2024)

Written in niners, nine-line poems that are a “post-punk” twist on the Anglophone sonnet, Nat Raha’s apparitions (nines) is an animated depiction of queer, trans, and Black and brown life amidst contemporary concerns such as capitalism and state power over the people.

Raha’s experimentation makes for bright, vivid poems, spacious fractals that are easy to digest and enjoyable to move across. “Course edges ecstatic / dissolved w/ love , open soul / all eyes generosity // we gossip daggers as tender / as chiffon , we feed as commune // sneak laughter , lust across,” she writes, weighty and contemplative yet playful and delicious.

Poets, queer theorists, and musicians such as Anne Boyer, Frank O’Hara, José Esteban Muñoz, and Kindness direct Raha’s language, structure, and explorations. Twists in language and line breaks keep you moving through the collection at a clipped pace.

“& grrrl, who’re you to abandon / the beautiful // jettison // ways of being // … learning your rhythm from canvas / lubrication for your soul,” she questions, simultaneously urging us to live and embrace everything that makes us complicated and alive. Not a single poem drags its feet, as strange, voiced turns of phrase illuminate the visually sparse pages and give voice to facets of language not often explored.

In apparitions (nines), Raha “carries the damage into truth / & [pins] / echoes on a snare / saline in vox & lyric,” creating an addictive, transformative book you won’t want to put down.

Good Dress by Brittany Rogers

(Tin House, 2024)

Brittany Rogers’ debut opens with a clear proclamation: “I, too, want.” Pleasures here are not guilty — Rogers embraces them and, in turn, herself in Good Dress, a distinctive, brilliant collection of community, self, and Black womanhood.

“All seven sins, and alive,” she writes in “Detroit Public Library, Chandler Park Branch: Erotic Fiction Section,” a charmingly titled piece. “This is not a confessional, yet / the shelves watch me fill my hands / with possibilities.” Rogers not only reclaims sexuality but creates it — “Most girls shy / away. I glutton. I devour,” she shares in “Hunting Hours,” where men are “making a game of their lust.” “No one took me / this time.”

Across traditionally formed poems and those crafted as letters, therapy intake sheets, and library overdue notices, there is a gathering of autonomy via pleasure and self-awareness. Grief, the Black Detroit community, and materialism inform her explorations. “This grief heavy, wrapped around our throats. / Oh, how it makes us casket sharp, / so flashy the camera / can’t bear to look away,” she writes in “Ice Cam, Little Caesars Arena, February 2023.” The Detroit Public Library grounds us in this place of transformation and coming of age.

Matrilineal connection shapes the speaker through motherhood and personhood: “I belong to this line / of daughters; before I was born, her kin,” she writes in “Good Ground.” Rogers is fiercely curious and wonderfully tender; her poems, while playful and bold, are also sweet and gentle: in “To Tenderness,” hands “stretching for the sun’s / applause. What does not bloom / before your attention?”

A sharp debut full of bizarre, beautiful scenes and contemplations, the poems of Rogers’ Good Dress are certain to echo long and loud.

Impossible Things by Miller Oberman

(Duke University Press, 2024)

Exploring generational trauma with experimental form and charming voice, Miller Oberman writes to challenge masculinity and fatherhood, as informed by the death of his older brother, Joshua, at age two, and his life as a father years later. “And in your place an empty place,” he writes in “Joshua Was Gone.” “You, can I call you you?”

With excerpts from his father’s unpublished memoir, trans and queer theory, and spacious, visually striking form, Impossible Things traces boyhood lost and fatherhood gained, attempting to make sense of the impact of parenthood and childhood. “Now I am a man, I remind myself. And those are not the boys, any of the boys who had me choking on the lightness of air,” he writes in prose poem “‘if this was a different kind of story id tell you about the sea.’”

While his musings are tentative, careful, Oberman’s images are crisp and vivid. In “How to Sleep,” “Your night lamp, blue and ship shaped, / now without a light, and I a song, and Mama / a prayer … // Nothing undone.” Identity and recognition of self weave through these poems, as Oberman writes, “I have become a lost name / as anonymous as grass” in “Jewish Cento, 1957.”

But amidst these internal investigations, the loss of Joshua inhabits — in “Memoir XIIi,” simply, “Joshua / I am flooded // all over.” In another italics-only, heavy white-space piece, “Memoir Cento,” “Talk to me, Joshua. / It feels so lonely, this touching. / This most tender of pleasures.” In this language, Oberman crafts a shared disconnection, one that reverberates throughout.

Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon

(Knopf, Oct 2024)

With tender wildness and rough-palmed love, Emily Jungmin Yoon’s newest collection reminds us just how untamed we are. Language is profound and simultaneously shies away from clear meaning: “Words reflect the world, which is to say nothing makes sense,” she writes in “Affection.”

At the same time, Yoon wrestles with the uniquely human state of our world, such as in the essay-like “I leave Asian and become Asian,” exploring Asian American identity. Pushing against labels, the speaker writes “to become [their] own historian . . . an act to perverse [themselves] against forces that try to diminish and distort.”

Explorations through and about the body are also central to the book; endings known and unknown; life and everyday experience. Reflections on environmental breakdown highlights our deep-rooted connection to the natural world: “My grieving mother brings the forest inside, a green excess,” she writes in “Related Matters.” “I want to live. Nowhere, but still, with desperation, I want.” This desire is palpable throughout Yoon’s collection, driving the speaker’s ruminations. “It made sense: you have to keep living / beyond surprise for desire to return,” she says of “The Greenland Shark.”

Yoon has a steady, reaching tone, urging us to consider the questions she brings to the page: “What is your soft body capable of?” (“The Greenland Shark”), “Are we? Of our bodies?” (“Body Of”), “What do I have / to do // with this place?” (“Gray Areas”). Yet even as uncertainty dominates, Yoon makes hope via love clear: “I dread the future and I can’t wait // to keep living with you … / I have no confidence / I won’t be born non-human. Or maybe that // will be considered lucky.”

Blade by Blade by Danusha Laméris

(Copper Canyon Press, Oct 2024)

Danusha Laméris’ third collection is a book of marvel, microscopic observation, and untamed want. Out of a “hungry mouth,” Blade by Blade moves through the earth with joyful precision. Following the deaths of her brother and son, Laméris searches for pleasure and connection. In “Fire Season,” “an epoch of water / laying low under the white- / capped waves. / I have wanted to live / in this paradise forever, / to dwell here on this / cracked continental edge.” The earth and all its lush, terrifying landscapes provide the speaker sensual delight and new beginnings.

The collection offers rich, visceral scenes that make us wonder, “What is it we give our lives for? / A mountain, a fire, a view from the cliff,” as Laméris writes in “Lava.” Or maybe “a mix of stimuli that / sends my senses keening / for a world I never even knew,” as illustrated in “Clydsedales.”

Clean, long lines create a smooth, pleasurable reading experience; Laméris’ voice is direct and grounding. Letting bliss take root and return, she shares intimate moments with lovers, marveling at “How there was something your body / said to mine in its halting speech of torso / and bicep, its vocabulary of fire” in “To Break.”

Even amidst climate destruction, a world changing the longer we look, in “Today the Pleasures,” Laméris makes it clear that none of that matters: “Yes, the world is falling down, death taking / a stroll down every street. And yes, it’s getting hotter / by the hour. And still, today the wind / has quieted and the dogs next door announce / their gods, who, so far, keep lifting the sun / and letting down (just enough) rain.” Taking us across bodies of water, grasslands, volcanoes, and downtown squares, we arrive at joy reclaimed.

Book of Kin by Darius Atefat-Peckham

(Autumn House Press, 2024)

Inhabiting a two-way graveyard, the living and dead mutually haunt each other in Darius Atefat-Peckham’s disquieting, gorgeous debut. “My heart stops each time I think of losing someone / I actually remember. Little reason to delay my everyday / haunts,” he confesses in “Sundered Sonnet: If We Should Be Ghosts.” “I’m a ghost / fearing man. I go to the graveyard every birthday eve, calling. I break / like the dog gathering on a boy’s glasses.”

Tracing the coming of age of a boy afflicted by the loss of his mother and brother to a car accident, Book of Kin draws from Rumi, the words of Atefat-Peckham’s mother, and Persian epic The Book of Kings; grief and joy are realized through the connective tissue of Iranian heritage and love that lives through grief. In “Death Report,” time shapeshifts: “I tell // the time by how hot / my tongue became. Her face // a hazy glimpse of moon—far, far.”

Atefat-Peckham’s voice is sober and bright, traveling an emotional expanse of reconciliation through collective memory. Hands convey shared domesticity: In “Here’s A Love Poem Sleeping,” “What // I came from. Hands. Stars // all around”; in “Heathcliffs,” “I want / to make it all wuthering, whatever / that means. I want to be clothed, fed, taken / care of. The hands of my love.” In these scenes, lack is palpable, even as the speaker emphasizes their emotive abundance.

Like a dream, these ghostly figures meet in unlikely places — and fittingly, “Persians take special interest / in dream,” he writes in “Second Mother.” “In dream // my professor presses Farsi / into my mouth like gol, / refusing to take soil. It is not // prophecy, but everything / below.”

With steady breath and imaginative relation, Book of Kin is a stunningly sure, transformative debut. In the words of the collection’s titular poem, in which the speaker moves toward reconciling what has been lost and what remains: “The Boy-Seeking kisses / the archive of our breath. this is how / He learns to breathe.”

Turi Sioson is a queer, Filipina-Italian American poet, editor, and publicist based in Austin, TX. She’s the editor and publicity director at Sunstroke Press and a reader for ONLY POEMS and Abode Press. Her poetry and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in The Hopkins Review, Epiphany, The Texas Review, Sunstroke Magazine, Freshwater Review, and The Luna Collective, among others. She’s worked as a publicity intern at W. W. Norton and will continue her education in publicity at Farrar, Straus and Giroux this fall. She holds a BA in English and Honors Creative Writing Certificate in Poetry from The University of Texas at Austin, and a copyediting certificate from Emerson College.