11 Poetry Collections That Marry Mysticism and the Human Body

A list of books exploring the liminal space between body and spirit, sex and soul, mind and matter

by Dani Kuntz

The autumnal equinox has passed and fall is officially here! With fall comes a feeling that enthralls both writers and readers—the presence of the unknown, the autumn air dense with energy and beings that lie just beyond our perception. But as humans, how do we reconcile spirituality with the grounding reality of our bodies?

Each of these eleven poetry collections seek to uncover the answer to this question. There is no end to the poets interested in the marriage of mysticism and the human body, from more familiar poets such as Ada Limón and Gregory Orr, to lesser-known poets like Mary Szybist and D.S. Marriott.

Whether you’ve read some of these titles or they’re entirely new to you, we are certain you’ll find a book to keep your spirit going this season!

Bright Dead Things by Ada Limón

Seven years before her appointment as the 24th U.S. Poet Laureate, Limón published her fourth collection, Bright Dead Things, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. You may be familiar with the feeling of displacement or readjustment one experiences when choosing to move to a starkly different place, but in “The Last Move,” Limón is blunt about the effect such a change has on her spirit: “This is Kentucky, not New York, and I am not important.” As she reflects on her past life in New York where she was “freely single, happily unaccounted for,” she imagines her body separate from herself. So separate, and even bothersome, that “I’d press her limbs down with a long pole / until she was still.”

A few pages later, in “Miracle Fish,” one can only empathize as Limón writes, “I used to pretend to believe in God. Mainly, I liked so much to / talk to someone in the dark.” Then, in “What It Looks Like To Us and The Words We Use,” Limón speaks to a friend who questions Limón’s belief in God:

...I believe in this connection we all have

to nature, to each other, to the universe.

And she said, Yeah, God.

Of Being Numerous by George Oppen

The mention of “1969 America” likely yields a very specific, turbulent image in the minds of Americans and citizens of other nations. What sort of book, then, do you imagine would be the winner of the 1969 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry? One that questions everything, of course.

In Oppen’s Of Being Numerous, the title poem is several pages long. The mysticism is apparent from the very beginning, as Oppen states in the first section, “There are things / We live among ‘and to see them / Is to know ourselves’.” Oppen frequently uses the passive voice, indicating a sort of disconnect from the self, from the body. In section 3, “The emotions are engaged / Entering the city / As entering any city.” Yet, in section 7, we are:

Obsessed, bewildered

By the shipwreck

Of the singular

We have chosen the meaning

Of being numerous.

The individual always struggles within the abstract crowd. How does one exist in this world if not by outside perception? Section 15 has the answer:

Chorus (androgynous): ‘Find me

So that I will exist, find my navel

So that it will exist, find my nipples

So that they will exist, find every hair

Of my belly, I am good (or I am bad),

Find me.’

Incarnadine by Mary Szybist

Perhaps no other collection on this list is as explicitly about mysticism as Szybist’s Incarnadine, a National Book Award winner which offers the human body and lust as an entry point to understanding God. The first poem, “The Troubadours Etc.” sets the tone for the rest of the collection:

The Puritans thought that we are granted the ability to love

only through miracle,

but the troubadours knew how to burn themselves through,

how to make themselves shrines to their own longing.

In “Conversion Figure,” Szybist seems to fancy herself a troubadour (or trobairitz) as she writes in lyric,

I fell toward the pulse in your thighs,

toward the cool flamingo of your slip

fluttering past your knees—

Out of God’s mouth I fell

like a piece of ripe fruit

toward your deepening shadow.

But this speaker is interested in more than just love and longing. She sees the object of her desire as something that needs to be mystified:

Before today, what darkness

did you let into your flesh?...

Lift up your head.

Time to enter yourself.

Time to make your own sorrow.

Szybist’s lines are musical, but she also experiments with form in a way that can only be witnessed in the pages of her book—take note!

The Wild Iris by Louise Glück

Winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize in literature, The Wild Iris by Louise Glück is a classic in its genre. The title poem immediately envelops us in something otherworldly as Glück writes,

Hear me out: that which you call death

I remember…

You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again…

Glück delves into natural, corporeal description in the first “Matins” poem of the book. Supposedly, “depressives” hate the spring, but Glück makes another case:

“... being depressed, yes, but in a sense passionately

attached to the living tree, my body

actually curled in the split trunk, almost at peace,

in the evening rain

almost able to feel

sap frothing and rising…”

For Glück, it is as if both the spirit and the body are connected to the “living tree.” This suggests that earthen bodies may sustain one who is suffering from depression—one who needs sustenance the most. With the very real effects of SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder), The Wild Iris makes for fantastic fall reading.

Sex & Love & by Bob Hicok

Bob Hicok's eighth collection, Sex & Love & (Copper Canyon Press, 2016), offers a unique exploration of the intersection between the corporeal and the metaphysical. The collection is driven by a central question, articulated in the poem “L'eau de vie”: “what is that?” This query emerges from Hicok's raw, sometimes uncomfortable depictions of physical intimacy, pushing readers to consider the ineffable quality of human connection that occurs through and beyond the body.

The poems navigate the landscape of the aging body, menopause, and the ghosts of unconceived children. Throughout the collection, Hicok grapples with the transformative power of physical experiences, exploring how pleasure transcends the mere corporeal to touch something deeper in our existence. It’s a powerful reminder that our bodies are not just vessels, but gateways to profound connection and understanding.

Hoodoo Voodoo by D.S. Marriott

English poet and scholar, D.S. Marriott’s Hoodoo Voodoo is a great example of a book that marries mysticism with the human body. It begins with subject matter not at all strange for the reader interested in the mystic. The first poem, “On the Whiteness of the Whale,” supplies us with immediate insight on what haunts Marriott as a writer. Crew and passengers are “astounded but not appalled” by the appearance of the notably white Moby-Dick, clearly holding a sort of mystical reverence for the creature, who is “a first evil no sooner touched / than a fear of reeling, inward.”

But what of the body? Another poem, “The Dream of Melby Dotson,” is Marriott’s visceral imagining of what Dotson, the early 20th-century black train rider, must have experienced in his dream before waking and promptly shooting the white conductor:

Rocking—the train’s motion—

that of an assault come alive,

in your throat,

…Rocking,

and the fear of becoming—when, as now,

the chance of taking air

with a cricked neck surprises—

makes every dream a grave.

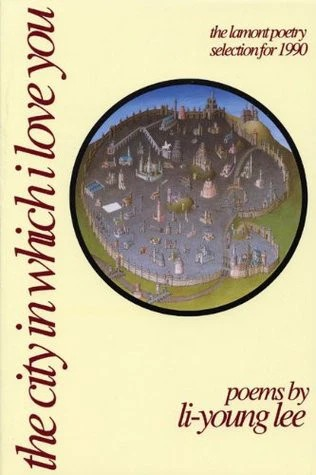

The City in Which I Love You by Li-Young Lee

As the Lamont Poetry Selection for 1990, The City in Which I Love You is a captivating and haunting read. Take, for instance, “This Hour and What is Dead,” in which the speaker experiences his brother

walking

through bare rooms over my head,

opening and closing doors.

The speaker wonders what his brother is looking for, asking, “What could he possibly need there in heaven?” If the reader originally thought the brother was alive, this line comes as a shock. In fact, it seems Lee is not at all pleased with the divine as he compares God to an old furnace whose breath is “of gasoline, airplane, human ash.” The tercet that finalizes the poem is powerful:

Someone tell the Lord to leave me alone.

I’ve had enough of his love

that feels like burning and flight and running away.

Though much of this collection deals with the mystic, Lee also elaborates on the body. The fifth and final section of the book consists of one poem: “The Cleaving.” This poem initially focuses on a butcher who the speaker observes chopping up his order. The head of a duck is flung from its body, and the speaker sees,

... foetal-crouched

inside the skull, the homunculus,

gray brain grainy

to eat.

He wonders,

Did this animal, after all, at the moment

its neck broke,

image [sic] the way his executioner

shrinks from his own death?

Once the butcher offers him the brain, he sucks it down; later, he philosophizes, “Bodies eating bodies, heads eating heads, / we are nothing eating nothing…”

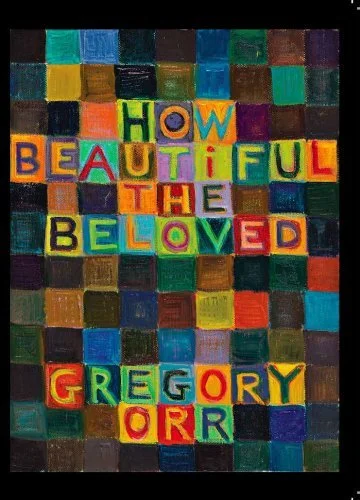

How Beautiful the Beloved by Gregory Orr

Reviews of Gregory Orr’s How Beautiful the Beloved call it “mystical” and “unwaveringly aimed toward the transcendent,” but this collection is not focused solely on the intangible. Orr’s short, meditative poems consistently refer to the beloved and “the Book,” both of which may incite a visible emotional reaction:

A thousand years ago,

A poet glimpsed

The beloved

And felt his eyes

Fill with tears

Felt his mouth

Become a smile.

The passage of time is visible, too, as Orr writes of his face,

More gray hairs

On my head

Every month.

My mustache

Almost completely

White now.

Sometimes, Orr writes about the body as its own entity:

Death of the body—

How many poems

In the Book

Urge us

To accept it.

Because Orr refers both to “the Book,” which one can assume is the Bible, and the body, he creates a solid link between the body and the spirit.

I shall leave you with a poem from How Beautiful the Beloved that readers and writers alike can appreciate:

Occult power of the alphabet—

How it combines

And recombines into words

That resurrect the beloved

Every time.

Breaking open

The dry bones of each

Letter—seeking

The secret of life

That must be hidden inside.

If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho translated by Anne Carson

In a list of poetry collections that “marry mysticism and the human body,” how could we not include Anne Carson’s translation of Sappho? In this translation, the Greek appears before each of Carson’s English translations, adding another layer of comprehension for those who are familiar with the aforementioned language.

Since Carson does not include only the fragments which appear as whole, but all fragments “of which at least one word is legible,” much is left to the imagination of the reader. Sometimes, Carson gives the reader a relatively whole poem which becomes fragmented partway through:

May he willingly give his sister

her portion of honor, but sad pain

grieving for the past

]millet seed

]of the citizens

]once again no

]

]

]but you Kypris

]setting aside evil [

]

No matter the loss of words, Sappho’s mythological/mystical influence is ever-present, along with her bodily observations. She writes,

...her dress when you saw it

stirred you. And I rejoice.

In fact she herself once blamed me

Kyprogeneia

because I prayed

this word:

I want.

Bone by Yrsa Daley-Ward

Before her foray into writing, Yrsa Daley-Ward was primarily an actor and model. Focused on the human body, acting and modeling are arts of their own, and it is clear through her writing that Daley-Ward feels pulled toward a variety of practices. Indeed, in her poetry collection, Bone, Daley-Ward shows us how prevalent mysticism and spirituality are in her life, how they push against the corporeal.

In “liking things,” Daley-Ward writes,

Women who were brought up devout

and fearful

get stirred, like anyone else.

… Get that all too familiar mix of fear and discontent

in the night. Want to do the things

that they Must Not Do.

For Daley-Ward, the body must be reckoned with spirituality—a struggle between devotion to religion and devotion to fulfilling one’s deepest needs. This struggle is evident throughout the book. In “emergency warning,” the speaker identifies the Lord as her witness:

You are one of those people, it is

clear, who needs help. I think you

should stop speaking in a low attractive

voice whenever you call…

…The Lord knows you are beautiful and unfair.

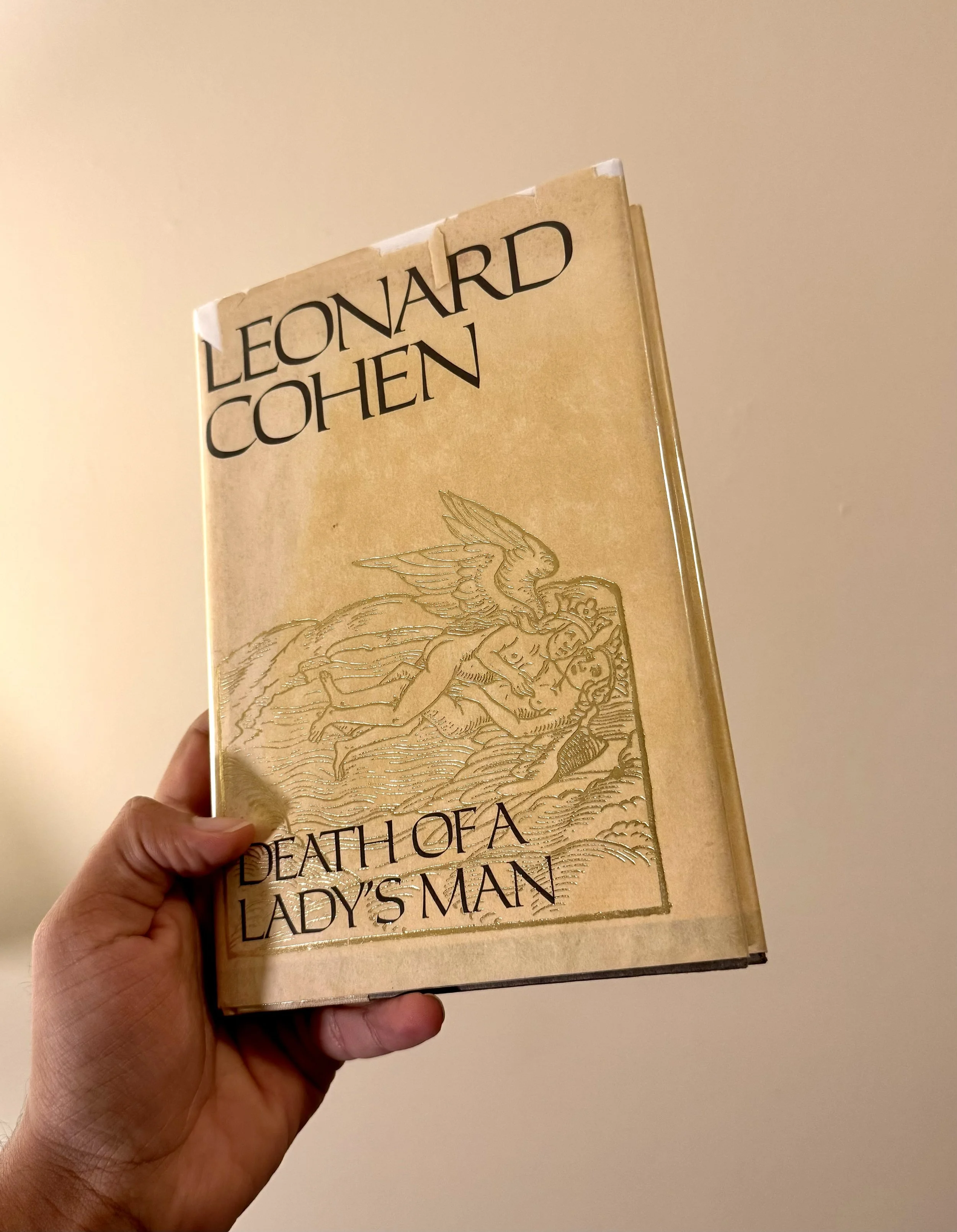

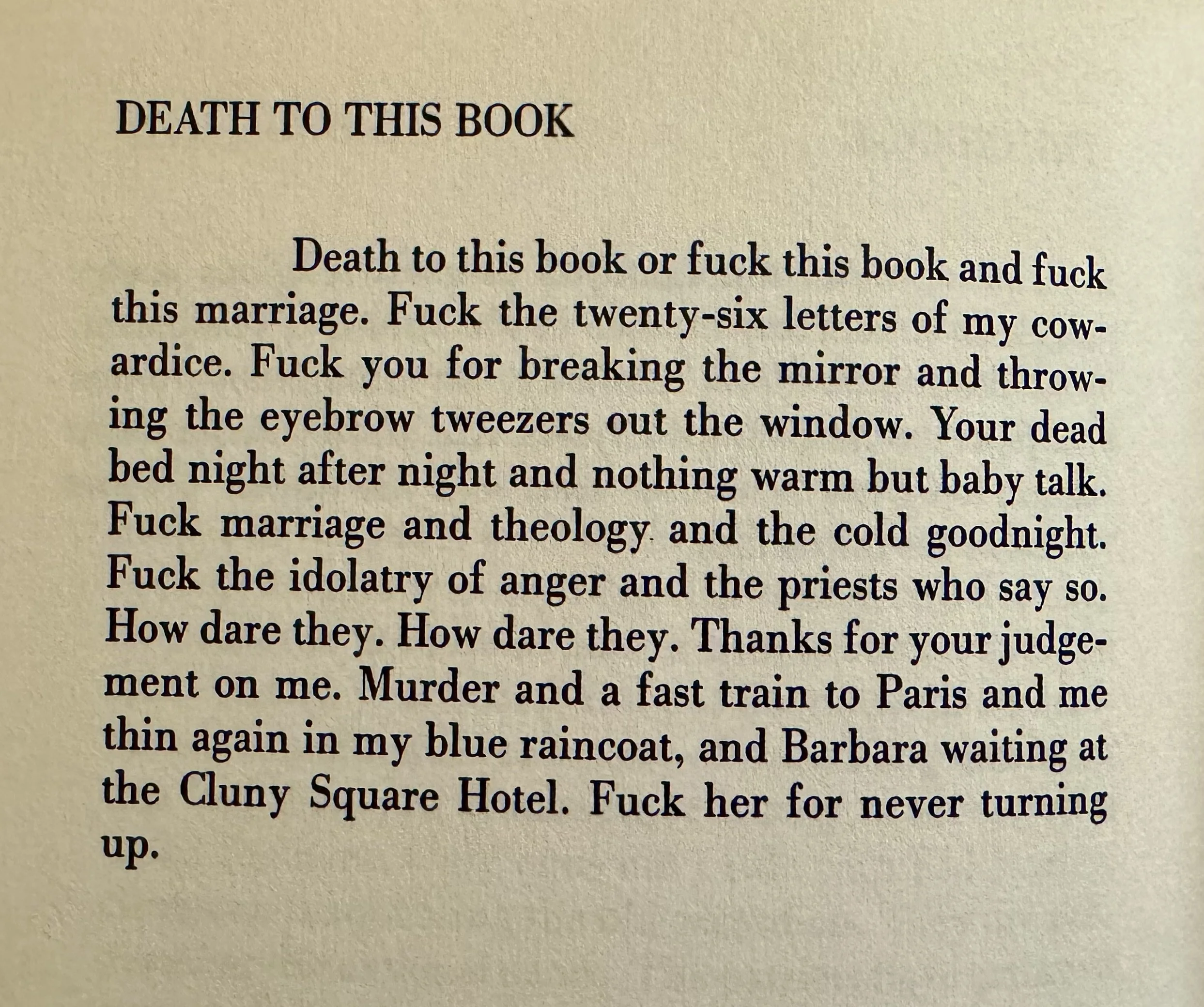

Death of a Lady’s Man

by Leonard Cohen

If there is one thing that Leonard Cohen proved to us through six decades of his writing, it is that he knew the human body, he remembered it well. As far as spirituality, he was connected to many higher powers, growing up in a Jewish household but discovered the sacred teachings of many other religions throughout his life. Death of a Lady’s Man blends poetry, prose, and commentary in a unique structure that explores the intersection of spirituality and sexuality. The book traces the destruction of a marriage, and a battle with the spirit. Most poems are accompanied by commentaries, creating a dynamic interplay between text and interpretation. This structure allows Cohen to constantly question and reframe his own words, embodying the book's central theme of union and separation. We witness marriage as a metaphor for various relationships: the poet with his art, the poem with its commentary, and potentially the reader with the text. It was in this collection that Leonard Cohen struggled with and perfected his marriage of sex and the spirit.

Originally from Arkansas, Dani Kuntz is an MFA Poetry candidate at UNR Lake Tahoe (formerly Sierra Nevada College). She teaches secondary English in Virginia, manages Sierra Nevada Review, and reads for ONLY POEMS. Her work appears or is forthcoming in The Talon Review, infinite↓scroll, A Thin Slice of Anxiety, AuVert Magazine, and eMerge Magazine. Using their poetry & essays, Dani hopes to achieve a sense of unity with readers. You can follow them on IG @daninkuntz