February 22, 2025

Sweet Elsewhere #3: Not This One

by Matthew Vollmer

The writer & professor examines the inevitability of failure in literary pursuits in the third essay of his series.

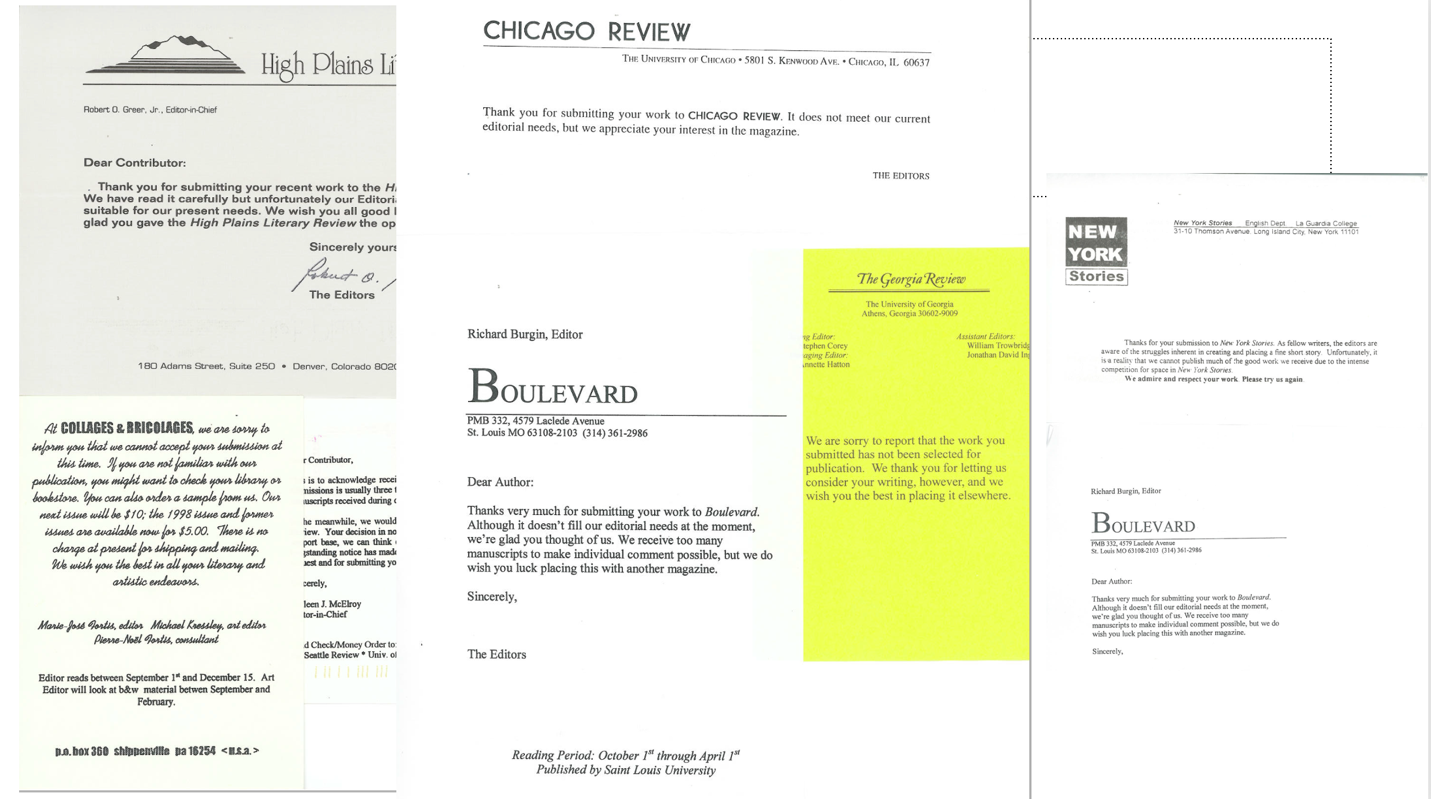

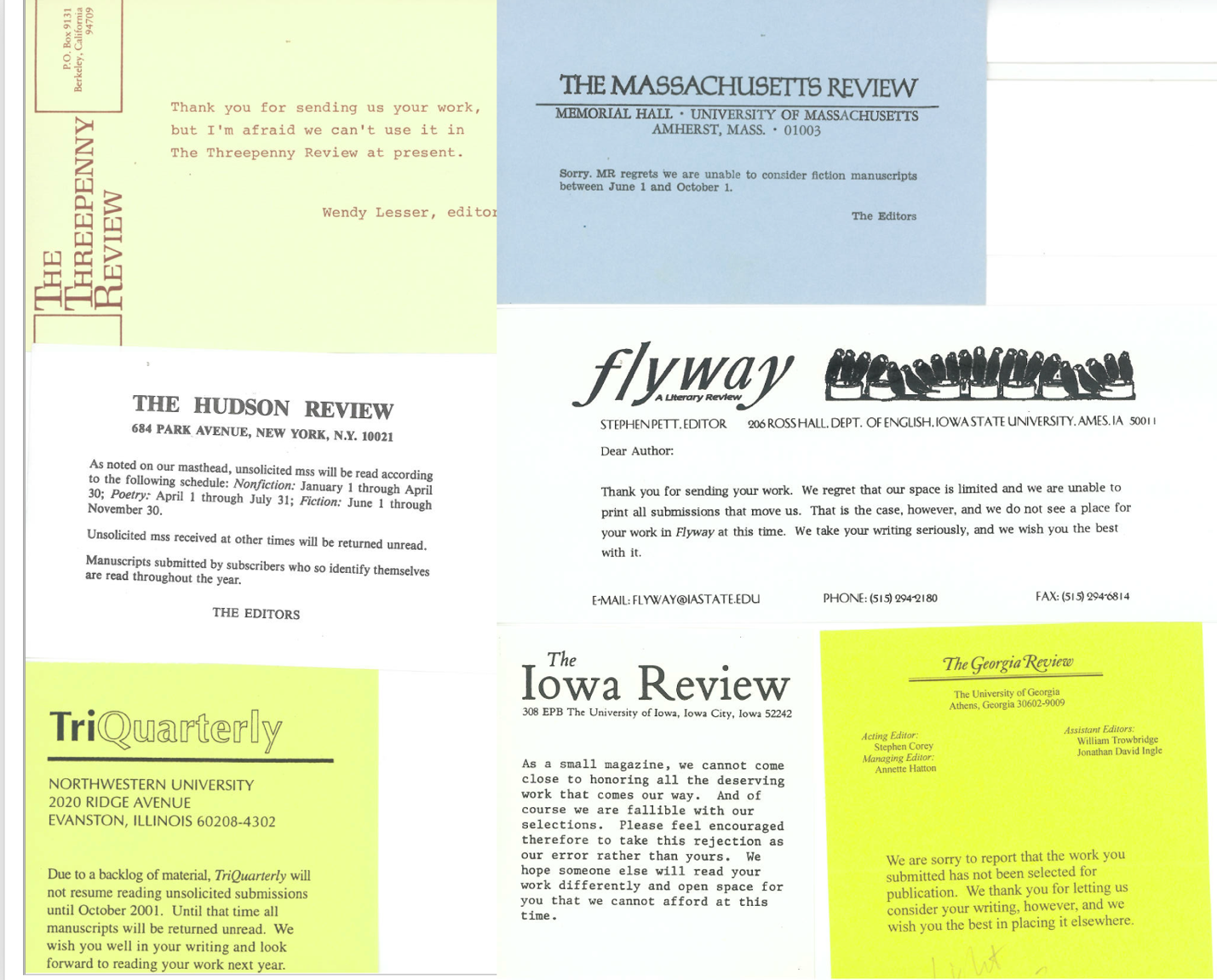

As I continued to submit to literary magazines, the self-addressed envelopes continued to appear in my mailbox, and because of my inexhaustible reserves of dumb confidence, I always thought, right before I opened one: this –this could be the one. But each envelope always only and ever contained a new form letter, printed on those small, rectangular slips of paper—in various shades—that were becoming like disappointing souvenirs, a collection of little flags of defeat.

Giving up, though? Not an option. Every rejection was another nail I pounded into the resolve of my unyielding determination—or whatever. I had no idea what the editors of Turnstile or Open City or The High Plains Literary Review thought of my stories, but I liked to imagine that the words I’d typed onto my laptop screen and printed out and sent hundreds of miles away had entered the brains of somebody. I hadn’t found “elsewhere” yet, but I was receiving pre-printed messages, presumably stuffed into the self-addressed, stamped envelopes by other human beings, and thus my existence had been however obliquely acknowledged.

Even so, I don’t ever remember being all that troubled by receiving them—at least not in the beginning. I expected to be rejected… until that day came when I wasn’t.

And that was, I told myself, only a matter of time.

Maybe I didn’t mind because the world had opened itself to me, and that felt like true enough progress. After having spent my entire academic career—from first grade through my sophomore year of college—in the care of Seventh-day Adventist teachers, I’d transferred to the University of North Carolina, explicitly to study English, and specifically creative writing. I’d survived the workshop gauntlet: in order to progress from one class to the next and arrive at your final capstone, you needed professor approval, and all of my teachers—a guy who’d written a novel about an Elvis impersonator and then, at the suggestion of an agent, actually taught himself to be an Elvis impersonator, and wrote a memoir about it; a woman whose bio always included the novel she’d written that’d been made into a TV movie; and a crinkly, sharp-witted old Presbyterian woman from Iredell County who had Flannery O’Connor Main Character energy—had praised my work. Furthermore, I’d submitted a story to the Louis D. Rubin Award, which honored an outstanding student of fiction by a senior, a a story titled “Illuminations,” in which a little girl is struck by a lightning bolt during a spring thunderstorm but is miraculously revived once the chalk painting—a reproduction of Tintoretto’s The Resurrection—dissolves in the rain and bleeds into her dress, much to the surprise and dismay of a group of people witnessing the event.

I had worked hard on this story: day after day, hour after hour, polishing, editing, shaping each sentence and paragraph so that the words fit together, images brightening, dialogue intensifying. Like slowly and diligently chiseling from shapelessness a voluptuous form. I knew I would win the Louis D. Rubin Prize. And I did.

I sent “Illuminations” out to a variety of literary magazines, all of whom rejected it: for whatever reason, I only kept the letter that Dogwood Tales Magazine sent me—an 8 x 11 page, a size that suggested the communiqué was somehow more official—and that instructed me to refer to the “enclosed rejection form,” which I reproduce here:

I knew my story wasn't bad—after all, it had won an award at my university, and thus proved, or so the powers that be claimed, that I was 'outstanding'—but in the eyes of Dogwood Tales Magazine, it was simply 'too long' and 'lacked a strong ending.' Their rejection came with a checklist: a taxonomy of failure rendered in efficient little boxes. There was something almost comforting about that checklist, as if the editors had seen so many manuscripts, endured so many writerly sins, that they'd managed to categorize every possible way a story could go wrong. My story wasn't 'predictable' or 'ho-hum.' At least it hadn't been 'too predictable.' At least my characters hadn't been deemed 'not fully developed.' The checklist suggested a kind of editorial omniscience—here were people who had stared into the abyss of bad writing for so long that they'd mapped its every contour. Length I could work on. The ending I could revisit. I'd been told by my mentors and friends to trust the process. And so I did.

Back in the day, I spent hours at UNC's D. H. Hill library, searching New Yorker archives for old, uncollected J. D. Salinger stories. I listened to space rock and alt country. Lived off cereal and microwavable foodstuffs. My teachers were mostly geniuses, except for the Shakespeare prof—a ruinous old jackass who claimed we only cared about “Mickey Mouse” and delivered brutal fill-in-the-blank quizzes. But there was the 17th century lit teacher who paced back and forth, delivering lectures with such passion I couldn't help but wonder if he'd done a bump of coke before class. And the creative writing professor who praised a story of mine where the main character shot a Jack O’Lantern with a shotgun for its “fecund masculinity,” thus validating me as a legitimate storyteller—one with “themes” and “symbols” and everything.

I loved these teachers. But inside, I was miserable.

My main problem—compounded by smoking too much weed—was that, aside from my roommate and a few people from creative writing workshops, I had very few friends. I lived in a dark, dank apartment on the edge of Carrboro, feeling like an imposter whenever I walked the streets of Chapel Hill or went to shows at Cat's Cradle. I'd sit on a concrete cube outside Greenlaw, home of the English Department, smoking cigarettes and watching hordes of students who, I imagined, were all similar in that they hadn't been raised Adventist like me. I found ways to dismiss them all: the slouching indie-rockers bobbing across the Quad on waves of lo-fi irony; the visual artists with their face-piercings dissing Duchamp; the Euro-trashy intellectuals flipping dramatically through de Man over quadruple-shot mochas. I rejected them all before they had the chance to reject me.

Time passed. I graduated. Drove my '87 Nissan Maxima to Wyoming, where I spent the summer at Old Faithful Inn, drinking honey raspberry craft beer and hiking the Tetons. Took the long way home: Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, L.A. Then landed the worst job I've ever had, working for an ill-tempered public defender who, thanks to a bout of childhood polio, limped around the office like a foul-mouthed pirate, barking insults at us all.

It strikes me now that small town lawyer could have learned something from literary magazines - their art of the gentle letdown, the way they could crush dreams while somehow leaving them intact. There’s a beauty to the form rejection; the best ones unfold like eloquent apologies disguised as encouragement and—sometimes, as with the case of The Iowa Review circa sometime in the early 2000s, self-deprecation:

(Geez, Iowa Review. That almost made me feel a certain way.)

As a genre, the form rejection is instantly recognizable. Pithy, graceful, versatile, clean. Often general enough to serve diverse audiences. Able to deliver crushing disappointment with minimal effort. The rejection note is a curtain preventing your entry and however delicately embroidered you can't see through it. Its language has evolved into a precise taxonomy of dismissal - from the brusque “not for us” to the encouraging “please submit again.” Like pressed flowers between pages, these notes preserve moments of literary aspiration suspended in perpetual almost. Yet there's something democratic about their ubiquity: even Plath's first submission of “The Colossus” was met with one of these pristine barriers, these polite bouncers at literature's most exclusive clubs.

At some point in my submission process—I don’t know when, exactly, but certainly after several years—actual human handwriting began to appear in the margins and white spaces of the form letters I received. An anonymous reader at Gulf Coast felt compelled to write a wobbly “Sorry”:

The odds, as always, were never in my favor. And yet, I kept submitting, driven by the stubborn belief—where did it come from? and what in the world sustained it?—that someday, somehow, I’d break through. Rejections taught me to persist, and reminded me that the only way to fail as a writer was to stop writing. I began to realize, too, that success wasn’t about talent alone. There were countless writers more gifted, more disciplined, and more widely read than I ever would be. But their existence didn’t diminish mine. And when nobody else cared—when there were no readers, no publications, no applause—I had to summon the will to keep going. To write was to disappear into the infinite possibilities of language, to build a lighted library inside myself that I could return to again and again.

I pretend that I don’t know where that obstinate confidence came from, but I have an inkling. One of my earliest memories is watching a 16mm movie directed by my grandfather—a dentist and wanna-be cowboy who lived almost all his life in the Piedmont of South Carolina, and who himself had suffered a major setback at age three when his older sister, aged six, held an axe above her head and warned him that he’d better move his hand off the chopping block, or else, and then proceeded to lop off three fingers on his left hand. (His mother, Pansy, purportedly buried them in a matchbox under a sycamore tree.) Anyway, the movie features me at 18 months. I’m wearing jeans and a matching jean jacket. My hair is blond and shaped, as was the style in 1975, in a bowl cut. The camera follows me and Doobie, the cocker spaniel, as I toddle down a gravel road and into the familiar darkness of my grandfather’s barn. I hop onto a riding lawnmower, turn the ignition, back the vehicle into the sunshine, drive it around a green field, and then return it to its place in the barn. Subtle and not-so-subtle breaks in the film suggest the hand of my grandfather’s editing, but the question remained in the minds of everyone who was ever subjected to this home movie: how in the heck did he do that?

My grandfather’s answer: “What do you mean? Matthew did it… all by himself!”

I have always known that this wasn’t the whole truth, but I liked to believe it, and glowed with pride every time my grandfather—larger-than-life, former boxer, spinner of tall tales that often featured him as the tough guy who took down bullies—bragged. That bragging, I believe, imbued me with something I’d need later: the dumb, unfounded confidence to imagine, despite all evidence to the contrary, that I could do anything I set my mind to, that I could make something of myself as an artist.

And maybe that’s what I inherently understood, back when I was lobbing those manuscripts into oblivion: that failure isn’t a verdict; it’s a process. Every rejection slip, every discarded draft, every awkward line of dialogue was proof that I had tried, and that I knew I could do better. To try, after all, is to live—to risk, to learn, to fail better. Because not only should you fail, you better. And if you think of yourself as a writer, there’s no other choice: you better try, and you better fail. In failing, you find what matters most—the resilience to keep going, the courage to improve, and the audacity to believe that you have stories worth telling, and that nobody can tell them better than you.

Matthew Vollmer is the author of two short-story collections—Future Missionaries of America and Gateway to Paradise—as well as three collections of essays—inscriptions for headstones, Permanent Exhibit, and This World Is Not Your Home: Essays, Stories, & Reports. He was the editor of A Book of Uncommon Prayer, which collects invocations from over 60 acclaimed and emerging authors, and served as co-editor of Fakes: An Anthology of Pseudo-Interviews, Faux-Lectures, Quasi-Letters, “Found” Texts, and Other Fraudulent Artifacts. His work has appeared in venues such as Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Ploughshares, Tin House, Oxford American, The Sun, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and Best American Essays. A winner of an NEA and a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he directs the MFA program at Virginia Tech, where he is a Professor of English. His latest book, All of Us Together in the End, was published by Hub City Press in 2023, and received starred reviews in Publishers Weekly and Foreword Reviews.