February 22, 2025

Sweet Elsewhere #2: Wonderful Verse!

by Matthew Vollmer

The writer & professor examines how not every acceptance is a success in the second essay of his series on navigating failure in literary pursuits.

Ah, the esteemed “National Library of Poetry.” Ever heard of it? Are you imagining, as I once did, when I spotted an ad in a magazine encouraging poets of all ages to submit their work, a gilded cathedral for literature? A place where great minds anthologized their epic yearnings, where my own words might sit shoulder-to-shoulder with greatness? Where someone might take seriously a poem I’d written about a sexy monster lovingly sucking my life force away?

I was 18, a wanna-be goth trapped in the body of a preppy Bugle Boy peg-legging his tapered slacks so his Air Jordans might pop, and whose understanding of art and desire was shaped by equal parts Robert Smith and paperback vampire novels. I didn’t just write the poem; I felt it—every cringe-worthy metaphor and purple turn of phrase. I stuffed the poem, likely printed on dot matrix computer paper, in an envelope, slapped on the requisite postage, and sent it off to the most official-sounding address I’d ever seen. The National Library of Poetry. How could they say no?

In my first essay on failure, I explored the crushing inevitability of rejection—the “we regret to inform you” slips that pile up like trophies in a sport where everyone loses. But rejection isn’t the only pitfall writers face. Sometimes, the thrill of acceptance can turn rancid, revealing itself as something far more dubious. Because, in the end, not all acceptance is created equal. I learned through an early “success” that, in hindsight, felt more like a failure.

Let me explain. Basically, it starts with this fact: that the first piece of writing of mine—ostensibly that aforementioned “poem’—ever accepted by a “legit” venue may be the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever written.

Forgive me.

It goes a little something like this:

“Vampiress”

Drizzle covers moon clouds cover sky.

A dark cloak covers a white trembling frame.

Candle lights the way.

I lie asleep, black beaded crucifix around my neck.

She comes floating through midnight hours, silk drapes her skull

She made from the purest ivory blue-tinted

With lips crimson red.

Jade eyes glowing green carnivorous passions aroused.

Inside thirst plagues her body.

I see you now behind the velvet curtains shedding your cloak,

Letting the velvet moonbeams kiss your naked body,

Your long fingers grasping the edges of life

You float silent again to my bedside

Your hands, soft and blue, slither across my chest to find

the heart that pumps your desires, a vampire’s wine

Your skin is so cold as it slides up against me

as you slide your tongue around mine.

Your wet mouth finds my neck, bursting with your life

Slowing sinking wite fangs into my flesh hot purple like bourbon

gushes into your throat flooding your body with warmth, leaving

me cold. I am dying but I love you vampiress seductress.

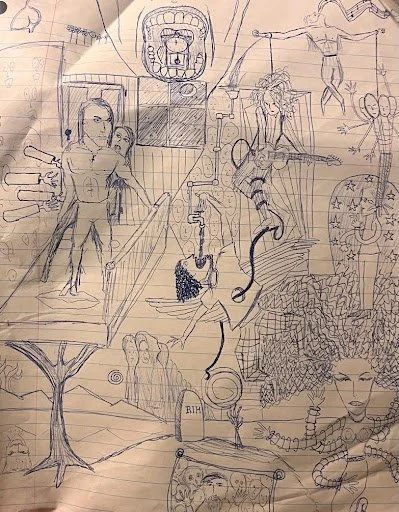

You may be wondering, as am I: What kind of venue would say “yes” to a poem of such “quality”? And furthermore: what was wrong with the person who wrote it? The time? 1992. The place? A Seventh-day Adventist boarding school in north Georgia. The situation: boys in one dorm, girls in another, soy meat entrees in the vegetarian-foods-only cafeteria, chapel twice a day, lots of songs about meeting your fellow students in heaven. No dancing, no rock and roll, no Dungeons & Dragons, no TV, no competitive sporting events. (Not to mention that vampires—and really all depictions of the undead—would have been sorely frowned upon.) Despite these deprivations I was not, I don’t think, depressed. Or maybe I was, a little. More likely: I wanted to be, back when I’d use an erasable pen to sear funereal Cure-like dirges about blood and knives and skeletons into the plastic interior of my Trapper Keeper folders, or draw—as the corresponding image proves—melodramatic collages of sensationalized despair that might include a goth-style guitarist; leafless, many-limbed trees; an open mouth with the kind of perfect teeth I’d seen a thousand times on models in my father’s dental office; arms reaching out of walls made of liquid; a skeletal hands emerging from a grave; a many-limbed woman with a storm of frizzy hair.

What was my problem? I don’t remember having many. Getting popped in the sack by one of my so-called friends, having miscellaneous items stolen from my laundry, pranksters messing with my alarm clock so they could watch me shamble zombielike to the showers at 3 a.m., that one guy who gave me an atomic wedgie—these were but exclamation points in the otherwise drab and predictable events of my tightly scheduled life at a Christian boarding academy.

Maybe I was listening to The Cure too much?

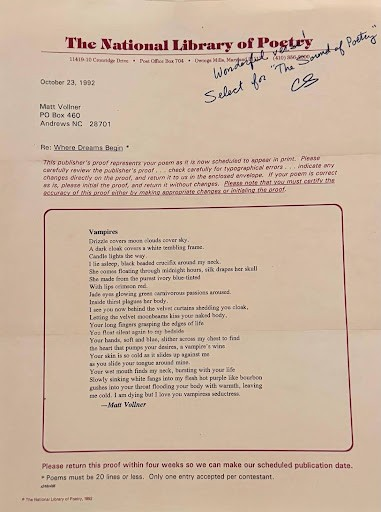

All I can say is that it was indeed a version of me—at 18 years of age, no less—who wrote the poem “Vampiress.” And while that fact is shameful enough on its own, the idea that I would have been proud enough to type it up and send it to an organization called “The National Library of Poetry,” is downright mortifying. To add insult to injury, the NLP accepted it. No joke. I still have the letter:

A person—a genius to be sure, whose name now escapes me—once said that drinking a La Croix was like taking a sip of mineral water and someone in the next room saying the name of a fruit. The titles of the volumes that the National Library of Poetry published in the 1990s—"Windows of the Soul,” “Dance upon the Shore,” “Tomorrow’s Dream,” “Journey of the Mind,” “On Wings of the Wind,” “A Whispering Silence,” “Echoes of Yesterday,” “Mists of Enchantment”—emit a similar vibe of soft-focus genericity: they could be the titles of songs on the demo your high school band recorded in your friend Scotty’s basement or the names of scented candles on shelves at Dollar General.

How much did the NLP request that I fork over in order to publish my “poem”? I can’t remember, but for some reason, “$75.00” stands out in my memory. Whatever the number, it ended up being high enough to deter my naïve 18-year-old self from purchasing the book: I never coughed up the change and therefore never saw the poem in print. It didn’t help their cause that they’d misspelled my last name (“Vollner” instead of “Vollmer”) as well as the title of my poem (“Vampires” rather than “Vampiress”). Whether I noticed it then or not, it’s clear to me now that the handwritten note on the acceptance sheet—“Wonderful verse! Select for ‘Sound of Poetry!”—is somehow part of the printed stationery, a mass-produced flourish intended to amplify the perception of legitimacy and care. But like, what person in 1992 who wasn’t a doddering 19th century aesthete would ever use “verse” to describe poetry?

The National Library of Poetry was a sham so transparent it’s laughable in hindsight—a scam dressed up in faux elegance: pre-printed stationery, hollow praise, and sloppy execution. My poem, so bad it practically indicts itself, proves their editorial “process” was a shameless cash grab, promising to print any submission (as long as the writer paid them) in order to fill overpriced anthologies. Add to that the cringe-worthy “wonderful verse” scribble in fake handwriting—decorative fluff designed to feign personal attention—and it becomes clear no one ever cared about the work itself. The misspelling of my name, amputating the second hook of the “m” in my name down to an “n,” and the botching of the title, stripped away the illusion of professionalism. Looking back, every detail—the lazy errors, the generic platitudes, the laughably earnest “National Library” branding—reveals the truth: it was never about poetry. It was about profit, wrapped in the cheapest packaging they could get away with.

Thirty-two years after receiving this “acceptance,” I typed the address of the National Library of Poetry—the one that had appeared in its letterhead—into a search engine. I clicked on Maps, summoned the image of a nondescript office park. A store called “The Magic Warehouse” claimed the address. An additional search revealed a series of reviews. All the recent reviews were one star. The newest review said:

I don't know what has happened to this magic shop, but DO NOT place an order with them. They charged my card, but never sent the product. They do not answer the phone, return messages, or answer emails. Is it terrible customer service or just plain theft? I don't know, but I will never order anything from them again. After about a month I gave up and contacted my credit card company to open a case and get a refund. So sorry to write such a review, but I am just trying to save others this type of experience. (The only reason I gave them one star is because this review would not post if I didn’t mark a star.)

The response:

Hi Paul - sorry about your bad experience. We have had some serious health issues with our staff and it may have impacted customer service. I believe Howard reached out to you to remedy your situation, but if there is still anything outstanding, please don't hesitate to email us.

According to its website, the shop once sold magician’s essentials: decks of cards pre-marked for sleight of hand, floating rings and smoke machines for dramatic reveals, stage-ready top hats with collapsible rabbits. But there was weirder stuff, too: hand-carved wooden spirit boards, “instant snow” powder for creating a blizzard out of thin air, and something called the “Invisible Assistant”—a contraption described as “an absolute game-changer for levitation effects.”

I imagined someone—a kid, maybe—waiting by the door for their “Assistant” to arrive, practicing their patter in the mirror. I pictured a small-town magician desperate for one last canister of “Mystic Fog” before a community center gig, clicking Buy Now and trusting, foolishly, that the Magic Warehouse would deliver. And then: nothing. No box, no assistant, no fog—just unanswered emails and messages flung into the void.

I thought about my letter from the National Library of Poetry: the way it arrived preloaded with praise. The handwritten note—printed, as it turned out, not just on mine, but every copy. My name misspelled, my poem’s botched title. A hook reduced to a straight line. A trick performed once, in the moment, before the mechanics become clear.

I thought about that earnest 18-year-old, scribbling tales of vampires in his Trapper Keeper, who'd nearly paid good money to see his name (or something close to it) in print. How fitting that my gothic fantasies had attracted a different kind of vampire—one that fed not on blood but on the desperate dreams of young writers, leaving behind nothing but empty flattery and depleted bank accounts. The magic wasn’t in their cheap praise or pre-printed acceptance letters—it was in believing, however briefly, that someone out there wanted to read what I had to say. The National Library of Poetry had mastered a darker art than any teenage goth could imagine: transforming youthful hope into profit, one form-letter acceptance at a time.

If failure has taught me anything, it’s that the worst thing you can do is stop trying because you’re afraid of being duped, embarrassed, or dismissed. Better to fail, better to embarrass yourself, better to be duped—because every hollow flattery and ridiculous misstep sharpens your ability to recognize what’s real. And so to whatever temporary employee at The National Library of Poetry retyped my poem and in the process botched the title and my name: thank you for helping me making it so easy to see through the illusion—for showing me that the soft-focus glow of acceptance can sometimes be a flashlight shone through wax paper.

Which doesn't explain why I'm staring at the cover of National Library of Poetry’s Tomorrow's Dreams—imagine a dreamy, watercolor-style illustration of a cloudy sky over a green rolling landscape that looks like it just won 3rd place in a high school art contest. The volume is available on Amazon for… $49.99. I already know what’s in there: a dolphin leaping through a rainbow of tears, a lost sock gathering lint behind a dryer, the lyrics to Depeche Mode’s “Somebody” retitled as “Shattered Mirror.” I’ve got points to burn, however, and there’s something deliciously transgressive to me about purchasing what amounts to the metaphorical equivalent of a graveyard of orphans, each one with a headstone that rhymes “pain” with “rain” and “soul” with “hole.”

Honestly, what do I have to lose?

[ADD TO CART]

Matthew Vollmer is the author of two short-story collections—Future Missionaries of America and Gateway to Paradise—as well as three collections of essays—inscriptions for headstones, Permanent Exhibit, and This World Is Not Your Home: Essays, Stories, & Reports. He was the editor of A Book of Uncommon Prayer, which collects invocations from over 60 acclaimed and emerging authors, and served as co-editor of Fakes: An Anthology of Pseudo-Interviews, Faux-Lectures, Quasi-Letters, “Found” Texts, and Other Fraudulent Artifacts. His work has appeared in venues such as Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Ploughshares, Tin House, Oxford American, The Sun, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and Best American Essays. A winner of an NEA and a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he directs the MFA program at Virginia Tech, where he is a Professor of English. His latest book, All of Us Together in the End, was published by Hub City Press in 2023, and received starred reviews in Publishers Weekly and Foreword Reviews.