January 24, 2025

Sweet Elsewhere: On Yearning, Failing, & the Endless Pursuit

by Matthew Vollmer

The writer & professor examines the inevitability of failure in literary pursuits in the first essay of his series.

I had been thinking about failure ever since a phone call with my friend, the poet Divya Victor. I say “friend,” but we’d only just met a month before, when she arrived on Virginia Tech’s campus as our first visiting writer for the 2024-2025 school year. I’d spent maybe a total of thirty minutes with her, escorting her to various locations on campus, and watching with awe an elegant presentation she gave on the image of blackberries in modern poetry, but during that time, she had won me over with her warmth and kindness and humor, and when it was time to say goodbye, we both agreed that we—as directors of creative writing programs—might benefit from future conversations. She proposed a date which she referred to as “embarrassingly far ahead,” indicative of her “scary calendar,” and now, because the date had arrived, I called her. We discussed a number of things during our conversation—Divya is friendly and intelligent and witty and empathetic, the kind of person who, as soon as you meet her, you feel like you’ve known forever—but the thing she’d said that’d stuck with me was her explanation of the series she’d come up with in her home department called “Fail Better.” You know the phrase. From Beckett: “Ever try. Ever fail. No matter. Try again. Fail better.” Divya is of the mind that writers and professors don’t talk enough about failure. I wholeheartedly agreed.

Recently, when I mentioned that I would be writing a column about failure to a younger friend of mine who is also a writer, he exploded in derisive laughter. What could I possibly know about failure? I was a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, a full professor at an R1 university, the director of an MFA program, the author of six books and over 200 single-authored publications. A winner of a fellowship from the National Endowment of the Arts, I’ve had work in Best American Essays and the Pushcart Prize Anthology. All these things are true facts that I’ve trotted out on many occasions when somebody’s asked me for a “bio.” But lurking behind them, like shadows that loom larger the closer you look, are all the failures: the false starts, the unfinished manuscripts, the abandonments, rejections, denials, and, in one case, the refusal of a dream press to publish a manuscript—after they’d led me to believe that acceptance was a done deal.

Failure, as it turns out, is baked into any writer’s DNA. Back in the beginning, of course, when I was merely a kid who loved stories, I understood precious little about failure. Words came naturally to me, always had, from watching anthropomorphized letters—namely the lonely lower case “n” crying on a hill above the sea—jumping to life on Sesame Street, to the days of listening to my grandmother read a story in the Childcraft anthology about Garnett and Citronella, two girls who’d hitched a ride into town with Mr. Freebody and subsequently got locked inside their local library. Teachers praised my writing. Friends laughed at madcap improvisations I recorded on cassette tape. Later, as I grew into adolescence, my own father proudly shared my poems—effusively romantic and often dramatic rhapsodies featuring moonlight and shattered hearts, printed on dot matrix paper—with his dental patients. Back then, writing wasn’t about trying and failing, and trying again a gazillion times; it was something I simply did. A reflex. A naturally occurring process—no different in kind than a belch or a fart. I mimicked voices, copied the rhythms of poets I admired, and experimented without hesitation. The act of writing felt as effortless as a half-court shot swished during a pickup game—fun, instinctive, unencumbered by doubt.

In college, I discovered that writing could be studied. Students could totally, like, major in it. I could spend years studying language and art and writing and someday, I could be a professional producer and/or studier of language. It wasn't necessarily advisable, if I wanted to make a lot of money, but money wasn't a part of this equation. The only thing that mattered was being able to do what I wanted to do. To do what I was compelled to do: write stories and poems.

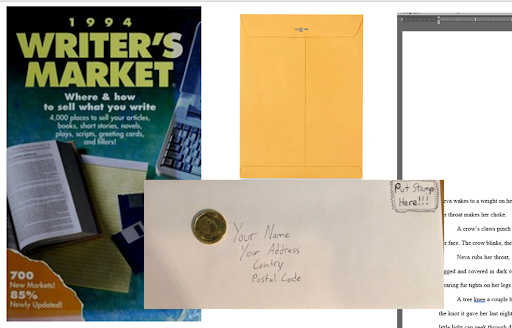

Eventually, though, I began to imagine that my writing deserved a larger audience, so I invested in one of those fat Writer's Market books and began preparations for submitting my work. I read about what the most prestigious magazines claimed they were looking for. I read what the least prestigious magazines were looking for. I packaged my manuscripts according to these publications’ specifications—double-spaced, with my name and address and phone number at the top right and the story’s word count on the left—along with an S.A.S.E. (self-addressed, stamped envelope) inside manilla envelopes, dropped them in the nearest mailbox, and began the months-long wait that would end when I opened the mailbox and was greeted by my handwriting, which I would immediately tear open to find… a form rejection.

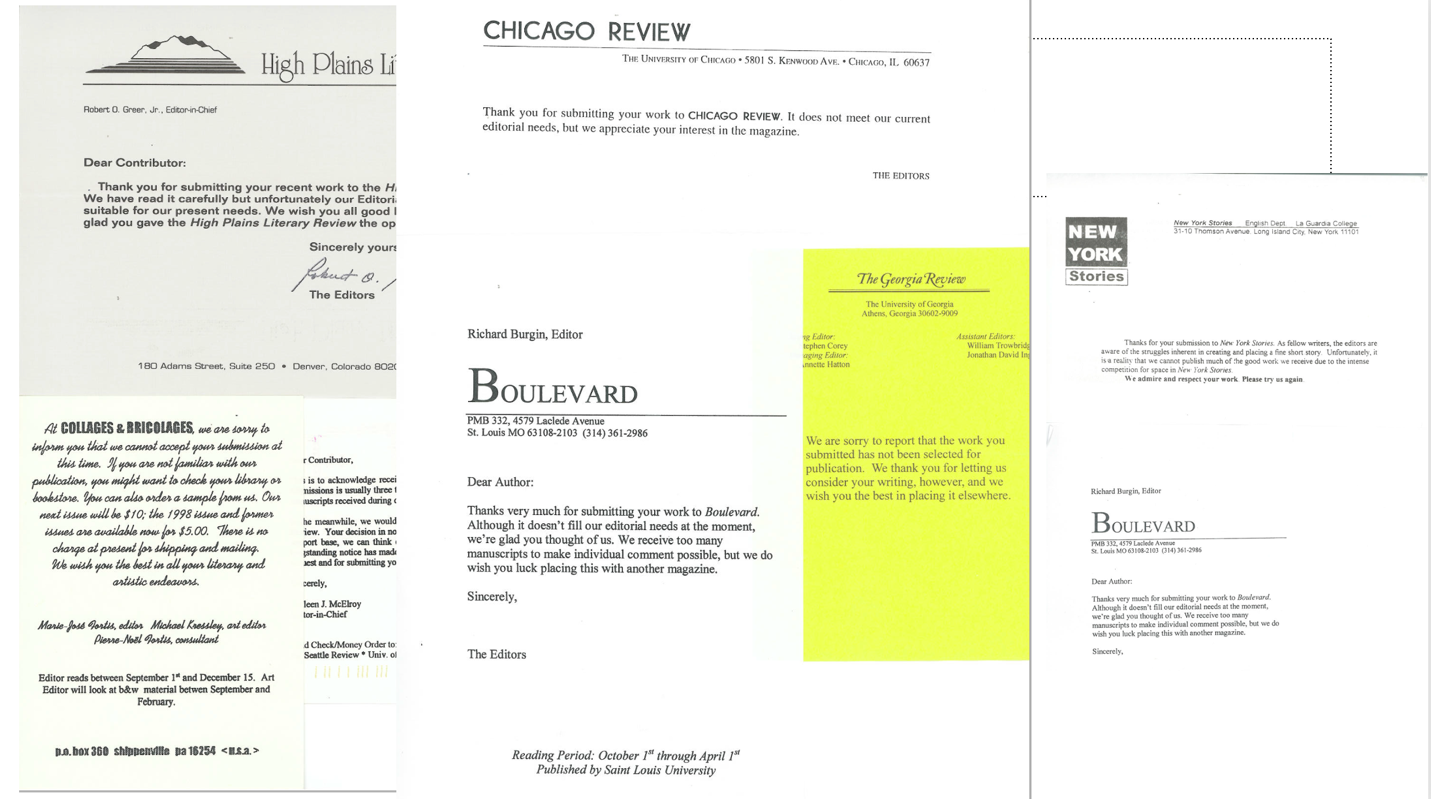

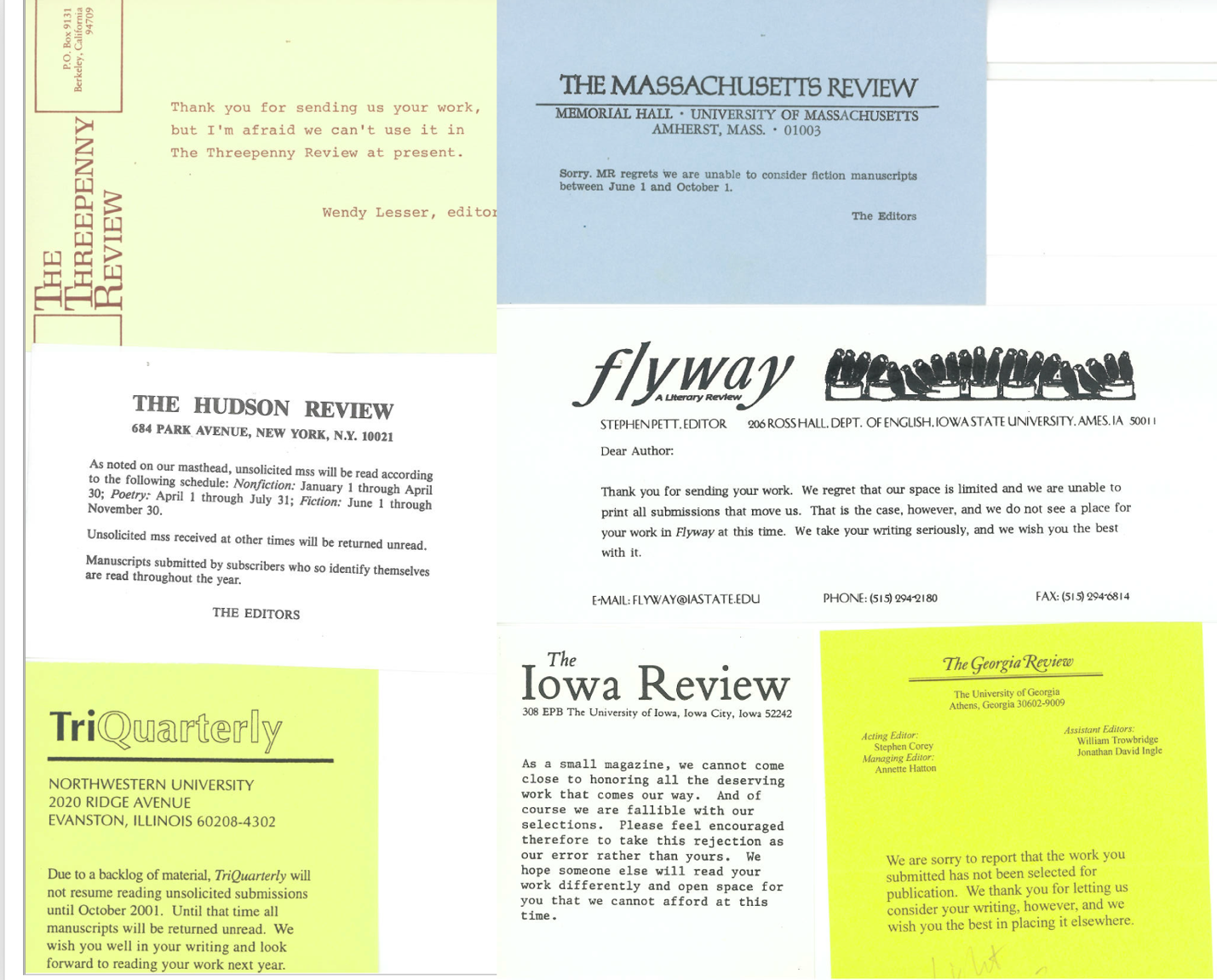

It was, of course, disheartening to unfold a slip of paper upon which a version of the following had been typed: “We regret to inform you that this material does not suit our needs at this time. We wish you the best in placing it elsewhere.” Oh! Sweet Elsewhere! That elusive country it took me so long to find! I hunted it for years, slinging my stories—and sometimes my poems—into the void, hoping that someday I’d land on its shores. In the meantime, I received a slurry of paper: rectangular slips of various widths and lengths and colors, bearing the insignias and titles of magazines in their identifiably distinguished fonts, which hovered above brief paragraphs that said things like: “We have read your manuscript with interest” (Carolina Quarterly) and “Thank you for sending us your writing” (The Threepenny Review) and “Thank you for your interest” (Portland Review). This gratitude—supposing gratitude was expressed—was always followed by a coordinating conjunction or a conjunctive adverb that allowed the message to swerve towards regret. “We regret that it does not currently meet our needs” (CutBank). “Unfortunately your story is not right for burnt aluminum.” Flyway regretted that their space was limited. Other magazines cited a “backlog of material” and explained that they were receiving so many submissions that it would be impossible to reply more specifically.

There was only one thing to do after receiving a rejection: return to the Writer’s Market, pore over their listings, and circle the names of journals who, according to their descriptions, welcomed “new writers” but not “simultaneous submissions.” I didn't know why magazines had such an aversion to simultaneity, didn’t know that they said this as a way to decrease the amount of submissions they received. Had no idea that literary magazines were notoriously understaffed and that the employees were overworked and underpaid and that the offices of these magazines and journals were piled with envelopes and paper and that there was no secret list that identified people as simultaneous submitters because that would be like piling a trillion more hours of work onto everything else they had to do and everyone was backlogged and a deluge of mail was pouring in by the minute.

What I didn't realize—and couldn’t have possibly comprehended—was just how many people a month were submitting. At a really good magazine, a couple hundred. At a great magazine? Thousands. Most of the manuscripts that arrived barely saw the light of day. Most weren't even seen by the editor because the editor had a cadre of interns (if it was a legit magazine) and/or grad student volunteers (if it was a literary journal published by a university) who’d been charged with dividing the wheat from the chaff. So, one of these readers (most likely a smart young man or woman in their early-to-mid-twenties) came into the office to put in a few hours of work or took a stack back home and sat down to read them. They were reading these submissions because they were in a graduate program or because they loved literature or because they wanted to be published themselves and thought that by reading what arrived at a literary magazine they might have a better feel of what not to write and what maybe they should write.

At any rate, these readers were people. And sometimes, one had to assume, they probably weren’t the sharpest knives in the drawer. Or maybe they were. But most of the time, they were probably of average-to-above average intelligence: people who’d read a lot and who were currently reading a lot, and they were keeping their eyes peeled for stories that leaped off the page. Stories whose authors were clearly in control. Stories that played by the rules but sliced straight to the heart. Stories that broke all the rules. Stories that were not only breaking the rules but inspiring readers to cheer them on because they were breaking the rules. This was what these readers wanted. It was what they were hungry for. But almost nobody was doing any of this. Most everybody sounded pretty much the same. They sounded like they were trying to sound like somebody else but ended up sounding like everybody else.

And these readers had become so adept at reading that they could read a first page, even a first paragraph or a first line, and instantaneously get a sense of whether or not they, the reader, had any interest in reading whatever little song and dance this so-called “writer” was up to. And if the answer was “not much,” the reader would most likely be thankful, because if they detected a boring or poorly conceived or bland story on the first page, that saved them a whole lot of work—there were twenty pages they could just slip back into the envelope and set on the “no!” pile. And perhaps the reader did this with some satisfaction, having received a number of rejections him or herself. Not that they took that much pleasure in it, but maybe—just maybe—it felt good to be on the other end of the rejection slip.

The odds, as always, were never in my favor. And yet, I kept submitting, driven by the stubborn belief—where did it come from? and what in the world sustained it?—that someday, somehow, I’d break through. Rejections taught me to persist, and reminded me that the only way to fail as a writer was to stop writing. I began to realize, too, that success wasn’t about talent alone. There were countless writers more gifted, more disciplined, and more widely read than I ever would be. But their existence didn’t diminish mine. And when nobody else cared—when there were no readers, no publications, no applause—I had to summon the will to keep going. To write was to disappear into the infinite possibilities of language, to build a lighted library inside myself that I could return to again and again.

I pretend that I don’t know where that obstinate confidence came from, but I have an inkling. One of my earliest memories is watching a 16mm movie directed by my grandfather—a dentist and wanna-be cowboy who lived almost all his life in the Piedmont of South Carolina, and who himself had suffered a major setback at age three when his older sister, aged six, held an axe above her head and warned him that he’d better move his hand off the chopping block, or else, and then proceeded to lop off three fingers on his left hand. (His mother, Pansy, purportedly buried them in a matchbox under a sycamore tree.) Anyway, the movie features me at 18 months. I’m wearing jeans and a matching jean jacket. My hair is blond and shaped, as was the style in 1975, in a bowl cut. The camera follows me and Doobie, the cocker spaniel, as I toddle down a gravel road and into the familiar darkness of my grandfather’s barn. I hop onto a riding lawnmower, turn the ignition, back the vehicle into the sunshine, drive it around a green field, and then return it to its place in the barn. Subtle and not-so-subtle breaks in the film suggest the hand of my grandfather’s editing, but the question remained in the minds of everyone who was ever subjected to this home movie: how in the heck did he do that?

My grandfather’s answer: “What do you mean? Matthew did it… all by himself!”

I have always known that this wasn’t the whole truth, but I liked to believe it, and glowed with pride every time my grandfather—larger-than-life, former boxer, spinner of tall tales that often featured him as the tough guy who took down bullies—bragged. That bragging, I believe, imbued me with something I’d need later: the dumb, unfounded confidence to imagine, despite all evidence to the contrary, that I could do anything I set my mind to, that I could make something of myself as an artist.

And maybe that’s what I inherently understood, back when I was lobbing those manuscripts into oblivion: that failure isn’t a verdict; it’s a process. Every rejection slip, every discarded draft, every awkward line of dialogue was proof that I had tried, and that I knew I could do better. To try, after all, is to live—to risk, to learn, to fail better. Because not only should you fail, you better. And if you think of yourself as a writer, there’s no other choice: you better try, and you better fail. In failing, you find what matters most—the resilience to keep going, the courage to improve, and the audacity to believe that you have stories worth telling, and that nobody can tell them better than you.

Matthew Vollmer is the author of two short-story collections—Future Missionaries of America and Gateway to Paradise—as well as three collections of essays—inscriptions for headstones, Permanent Exhibit, and This World Is Not Your Home: Essays, Stories, & Reports. He was the editor of A Book of Uncommon Prayer, which collects invocations from over 60 acclaimed and emerging authors, and served as co-editor of Fakes: An Anthology of Pseudo-Interviews, Faux-Lectures, Quasi-Letters, “Found” Texts, and Other Fraudulent Artifacts. His work has appeared in venues such as Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Ploughshares, Tin House, Oxford American, The Sun, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and Best American Essays. A winner of an NEA and a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he directs the MFA program at Virginia Tech, where he is a Professor of English. His latest book, All of Us Together in the End, was published by Hub City Press in 2023, and received starred reviews in Publishers Weekly and Foreword Reviews.