Reading Poems,

Revising Ourselves:

An Essay in Five Acts

by Lauren Peat

In this essay, poet Lauren Peat explores the poetic turn—seeking to understand how poetry can revise our way of seeing.

March 1, 2025

Act I

Toward the end of King Lear, the Earl of Gloucester is adrift, newly blind and reckoning with the callousness of the world. When Lear urges him to “read” his situation—to acknowledge that his callous treatment of his son, Edgar, makes him complicit—Gloucester replies: “I see it feelingly.”

Over 400 years later, many of us are still reckoning with the callousness of the world, slowly working to discern our own complicity. Shakespeare makes it look easy, but it’s no small feat to read our situation “feelingly”—to resist, as Gloucester suggests, letting “my thoughts be severed from my griefs.”

Seeing feelingly, though, is also the purview of reading poems. How often do poems stitch thought together with grief? If the real-world connection between thought and grief can feel ragged or unwieldy––if grief frequently works against our capacity to study a situation and then take steps to meaningfully change it––reading poems might be a way of rehearsing more attuned responses to the world.

By some accounts, every poem is a catalogue of change. For poet Randall Jarrell, “a successful poem starts in one position and ends at a very different one, often a contradictory or opposite one; yet there has been no break in the unity of the poem.”[1] Similarly, poet Peter Sacks has spoken of poems that “veer[] from one course to another,” their “way of being drawn off track to an unexpected destination.”[2]

Some poets refer to this phenomenon as the “poetic turn.” I like to think of it as the curving wake of a poem that’s revising itself, driving through first thoughts and feelings to arrive at something deeper. And when we read a poem, I like to think we’re carried by this wake; that we’re impelled, however subtly, to revise ourselves.

But how does a poem turn, and how do we measure a turn’s success? In other words, how can we tell if a poem has revised our way of seeing? In the spirit of the word essay—from the French essayer, to try—I’d like to embark on these questions, uncertain of where we’ll end up.

Act II

Gloucester brings to mind another cast of characters: the townspeople in Ilya Kaminsky’s collection Deaf Republic.

Living in an unnamed occupied territory, the characters in Deaf Republic are also reckoning with the callousness of the world. When a soldier shoots and kills a young deaf boy named Petya, the gunshot renders the entire town deaf. Like Gloucester, then, these characters must radically reimagine their perception of the world.

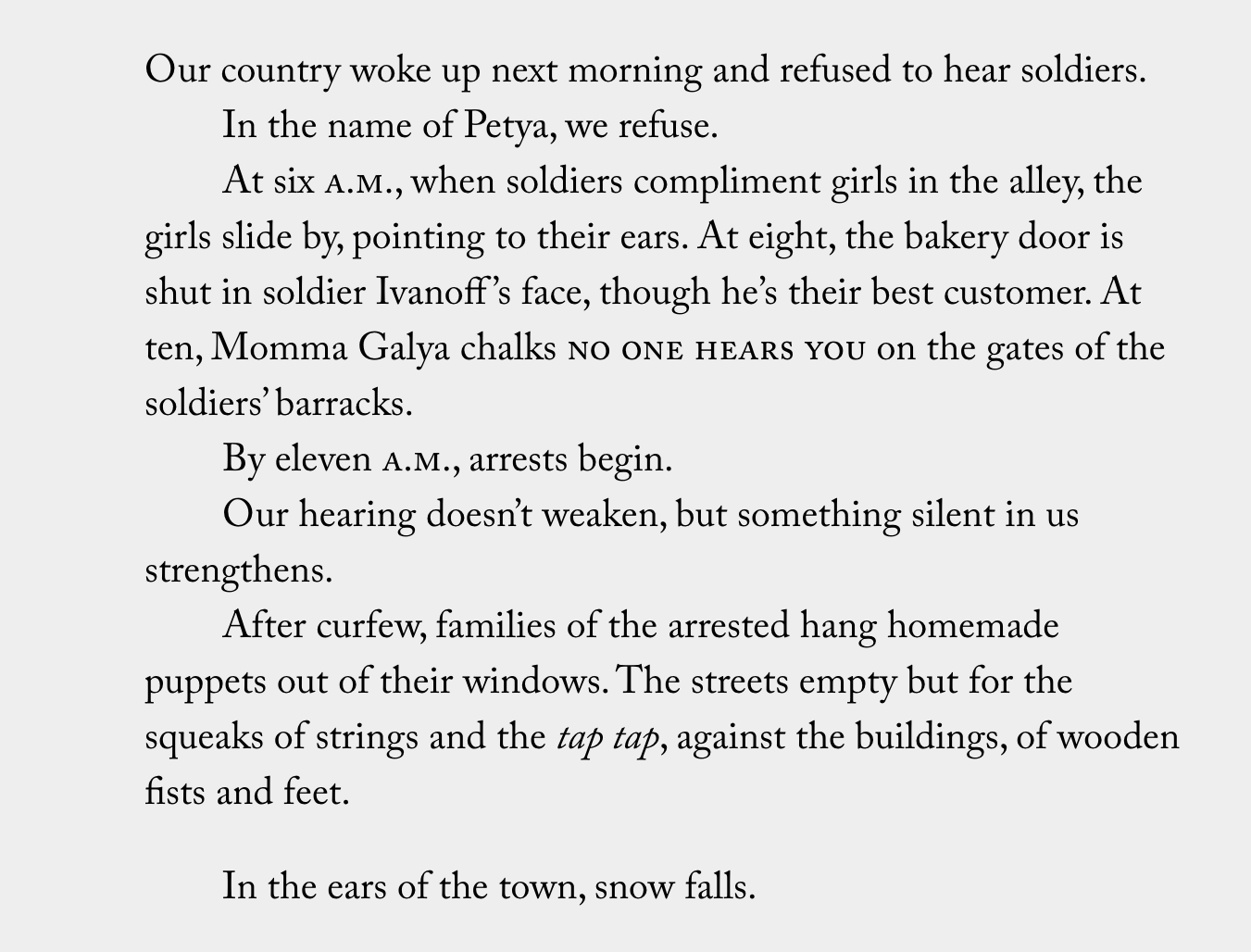

In “Deafness, an Insurgency, Begins,”[3] the character Alfonso narrates the origins of the town’s response. (The image that follows is part of the poem.)

First, how does the poem turn?

“Deafness, an Insurgency, Begins” turns on two levels: through the poem’s coordination of words on the page and the townspeople’s coordination of will in the world. These levels are in constant communication, the way the floors of a high-rise are made coherent by an elevator.

On the first level, like well-oiled hinges Kaminsky’s commas allow the lines to swing. “[W]hen soldiers compliment girls in the alleyway”—swing—“the girls slide by, pointing to their ears.” “[T]he bakery door is shut in soldier Ivanoff’s face”—swing—“though he’s their best customer.” Whenever the soldiers make a gesture, the adjoining clause claps back, opposite and unexpected.

On the level of coordinated will, this seems to counter Alfonso’s opening claim. While he alleges the country “woke up” and turned away from the soldiers en masse, the poem is composed of many smaller turns, each one emboldening the next. It’s only after the girls and the bakery rebuff the soldiers that Momma Galya writes the town’s refusal on the wall.

“By eleven a.m.,” the soldiers clap back themselves. Here the poem performs yet another striking turn: “Our hearing doesn’t weaken, but something silent in us strengthens.” (Like however, though, and yet, the word but is strong evidence of a poetic turn.) Once again, a comma stabilizes the line’s subversion. The silence is now additive, not subtractive; the body politic has acquired “ears,” a form of perception that bypasses the usual discourse.

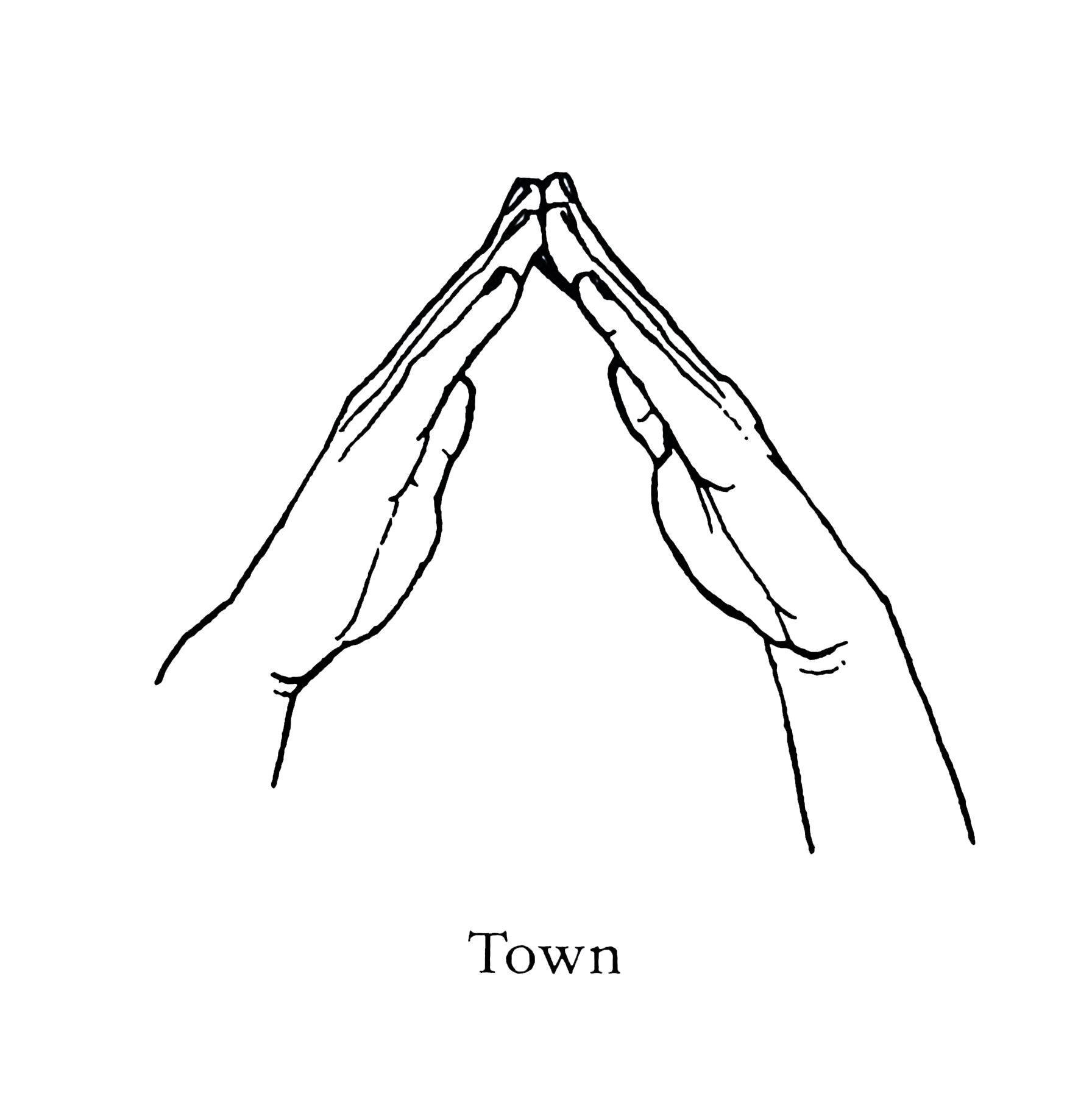

I’m most intrigued by the poem’s final movement, the sign for “Town.” Is there a better example of seeing feelingly than this? Under these changed circumstances, a person must properly feel to properly read. We can imagine soldier Ivanoff encountering this sign and mistaking its silence for insignificance; versed in the language of gunshots, he likely wouldn’t hear (or see) its expression of defiant solidarity.

The sign comes to signify much like the puppets do: encountered by those who have proved themselves unfeeling, and therefore unworthy, they appear worthless.

Act III

Kaminsky’s puppets also communicate on two levels: they convert the streets of the town into a stage and signal the poem as a stage for us, its readers. Both town and poem become spaces through which to observe, and even rehearse, change.

But. And yet. Puppetry is a well-known symbol for pretense. The practice of manipulating ligaments—of dressing them up to delight, even beguile—puppetry is posturing elevated to the status of art.

So should we not probe a little further? Press on and see if the townspeople’s turn will stand the test of time?

“And Yet, on Some Nights”[4] is one of the final poems in the collection. Narrated by Momma Galya, it appears shortly after Alfonso’s death at the hands of the soldiers.

The town’s response now quivers on the edge of a knife. While the residents have reverted to the old forms of discourse (“Years later, some will say”), the underground resistance carries on. The townspeople still sit on their hands; they still perform gestures of resistance to doors and trees. And “[w]hen patrols march,” they clear the streets. But to what effect? Mostly, only a few weak stirrings remain—a puppet resistance.

To my mind, this is the genius of Deaf Republic. The collection can be read in crosswise directions: on the one hand, a parable of radical change, on the other, a cautionary tale.

While the townspeople have achieved unprecedented breakthroughs in the way they read and respond to their situation, Deaf Republic suggests that breakthroughs are not safeguards against future calamity. That breakthroughs, like everything else, are prone to atrophy.

Act IV

I haven’t yet considered my third question—how to tell if a poem has revised our way of seeing.

When I read King Lear for the first time, when I read Deaf Republic, I do believe I saw things differently. I remember thinking a great deal about my role as a daughter, as a practitioner of language in a time of violence. But it’s difficult to quantify these revisions––to point to their concrete effects in the world.

In the end, seeing differently might be a question of degree. When we say “this poem moved me,” do we mean our perception has been irrevocably changed? Or do we mean we’ve been gifted a seedling that may or may not bear fruit?

Unfortunately, Gloucester’s ability to see feelingly doesn’t help him salvage his relationship with his son, Edgar. He continues to believe Edgar dead, and it isn’t until the play’s final scene that he recognizes the disguised “peasant” at his side. When he realizes his error, his heart “burst[s],” still “too weak,” Edgar claims, to support the change.

But Edgar also tells us his father’s heart burst “smilingly,” between “two extremes of passion, joy and grief.” So when Gloucester does, with his inner eye, finally see, he takes leave of his son with a smile, a tender greeting. Gloucester’s seedling may have sprouted too late, but it does sprout.

And the townspeople of Deaf Republic: while they may have surrendered, they have also endured, miraculously, in the face of gruesome discrimination. (It’s worth stressing that Deaf Republic is a masterful critique of ableism, the refusal to recognize different ways of engaging with the world.)

The townspeople’s resistance did spark a new way of seeing, one they continue to pass down. A highly flammable heirloom, ready at any moment to reignite.

Act V

Before we part ways, here’s one last text: an excerpt from a long poem I wrote at age nineteen, titled “Fable.”

Though I now cringe at many of its turns of phrase, “Fable” does, as Jarrell specified, “start[] in one position and end[] at a very different one.” It begins by charting the eating disorder that almost claimed my life at age eighteen—my affair, in the language of the poem, with an artist “intent on whittling me down.” It concludes with the speaker enacting her escape.

The following excerpt appears toward the end of the poem.

I took one bite The hunger roared

I took another It wept in anger &

relief

Cried itself to sleep in the drawer

of my stomach

Slowly The world looked ajar

I opened wide Walked on

Sometimes I can feel it at my heels

When I do I take out my easel

When I do I paint myself in

“Fable” was a confirmation of change, though the change wasn’t permanent. While I didn’t succumb to my illness, I did, on a number of occasions, relapse. I would lose ground, feel the illness at my heels, find all the doors I’d fought to open slowly closing. Never so decisively as the first time, but again, change is a question of degree.

At the same time, “Fable” became a kind of weathervane, a lighthouse—a structure I returned to as a way of measuring how far I’d veered off course. And when I returned to it recently, at age thirty, I was forced to admit I’d once again forgotten to keep painting myself in.

Poems aren’t manuals for living, but they do provide tools we can learn, again and again, to use. Gloucester must keep remembering how to see, just as the townspeople must keep remembering to send each other signs. Signs that signify: “I’m still here.” That mean: “Not only do I see your grief, I want to help you turn it into something else.”

Which is also how poems signify, sending out their flares, calling us back to the sparks of change we bury and sometimes forget.

[1] Randall Jarrell, “Levels and Opposites: Structure in Poetry,” Georgia Review, 50.4, 1996.

[2] Peter Sacks, “‘You Only Guide Me By Surprise’: Poetry and the Dolphin’s Turn,” Judith Lee Stronach Memorial Lectures, University of California, Berkeley, 2007.

[3] Ilya Kaminsky, “Deafness, an Insurgency, Begins” from Deaf Republic. Copyright © 2018 by Ilya Kaminsky. Used with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, graywolfpress.org.

[4] Ilya Kaminsky, “And Yet, on Some Nights” from Deaf Republic. Copyright © 2018 by Ilya Kaminsky. Used with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, graywolfpress.org.

Lauren Peat's debut poetry chapbook, Future Tense, was recently published by Baseline Press. Her poems and translations have appeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, Asymptote, The Malahat Review, The New Quarterly, and World Literature Today, among other places. Her writing is also featured in the repertoire of acclaimed vocal ensembles across North America. Translation Editor for the online poetry magazine Volume, she lives in Vancouver, Canada.