March 14, 2025

Navigating the Borders Between

the Past, Nature, and Ourselves

An interview with Patrycja Humienik

by Phil Goldstein

LETTER TO ANOTHER IMMIGRANT DAUGHTER

for Malvika

Were they dead honeybees or little beetles

you kept in a jar? A film canister. Isn’t memory

impossible! I take copious photographs

against this inevitable outcome.

Failure, though, is essential to transformation.

You are citrus, hibiscus, what else?

At the park, her fingers in my hair, discussing

desire and theology, I’m reminded of our chats

about how to practice asking for what we really want.

Adnan wrote to Fawwaz, I thus renounced the idea

of writing you a formal letter on ‘feminism’,

and began living that which was given to me.

The backs of my knees are more sensitive than

I’d realized. I’m moved by the affection between

two men on the bus thundering about the difference

between the Dollar Tree and Dollar General—

I think good sex helps me adore the world.

PHIL GOLDSTEIN

The speaker of We Contain Landscapes carries all this longing for so many different things—for love, for pleasure, for tenderness, for connection to their parents and their grandparents' homeland, to their homeland, and to connection—period. And there are a lot of very direct references throughout the book to the children of immigrants. Do you think the children of immigrants have a longing within them that people who aren't the children of immigrants don't have?

PATRICJA HUMIENIK

I can't speak for anyone else's longings. I hope for the“we” in my title to be an invitation and not a presumption. I do think there's something particular to the experience of a child of immigrants’ relationship to the idea of home and to self-concept. In my case, I wasn't able to even go to Poland for the first time until I was 19. And so the motherland was a myth and dream and haunting. And even now there's so much I don't know. I catch myself romanticizing this place that doesn't even exist, because it is a place constructed in part by what I've heard about it, a patchwork of anecdotes from my parents growing up there and my limited visits. And so, my connection to the Polish language is in some ways stuck in time because I'm not living there engaging with the ever-evolving language. There's no way of catching up with that longing. Even if I were to move there, my childhood was here in the Midwest, and so place and longing are entwined for me in a way that does feel really particular in that sense. Each immigration story is so particular, but there's this mythical aspect to the homeland.

PHIL

As I mentioned to you before, I have some Polish ancestry, but it's much more distant and kind of even more mythic for me than for you. My maternal great-grandmother was Polish. And so as you're talking in your last answer, about this push and pull between immigrants, their homeland, the new places they call home—and obviously in this book it’s Poland specifically—what do you think it is about this country—the people, land, church, the music, the art, the history—that makes a Polish immigrant’s journey different perhaps than someone coming from some other place? Is there a difference in the bind to the place or a difference in what you bring with you?

PATRYCJA

I think about this a lot because Poland is a country that has been repeatedly taken off the map and its borders were ever changing. And there's a poem in the book that engages directly with this, “Borderwound,” with the idea of the great many Polish poets who were born in cities that now no longer belong to Poland. So there's thisfascinating national identity of a land that literally continued to be reshaped and remapped and recharted. And it's also a country with a deep cultural connection to Catholicism. And so the history of the Solidarność movement, of the labor movement that fought political repression, happened with the support of the Catholic church, which makes for a very complex political consciousness that I'm still thinking through, especially considering the violent legacies of the church. There's this desire, I think, in a country that was so wronged by surrounding nations over centuries, to locate its own power.

There's this complexity of a relationship to a desired dominance, in relationship to whiteness, that I think must be reckoned with. And so I think any Polish diaspora writer is sort of forced to reckon with these big questions of religion and capitalism, whether or not we want to, and these are complexities I hesitate to even articulate because of how much more I have to learn. But there's also this other thread for me, the maybe more romantic one, which is growing up with some sense of Polish literature, this really rich legacy of Polish poets. There's this deep current of faith and hard work and questioning going generations back in my own family, and also in my sort of poetic Polish lineage. I feel at once the complexities of these sociopolitical forces, and this rich history of literature engaging with that too.

PHIL

One of the things that I love about the book is that there's this great mixing and intermingling of the personal with the geopolitical and sociopolitical. There’s a line in “Borderwound” that “every border is an open wound.” All borders represent a demarcation of some kind, whether it's from conflict, and that conflict could be something that happened a long time ago as the case is with Poland, or it could be something that's really fresh. At the same time, borders are a human construct because when you look at the planet from space, there are no borders. There are no lines except ones that are natural. And so that also brought to mind the idea of “we are landscapes,” that “we contain landscapes.”

I'm curious how you conceptualize borders and what it evokes in you. Because to me, these two things simultaneously, they're not real at all. But in the lived reality of so many people, the fact that we have borders obviously has a tremendous effect on people.

PATRYCJA

They demarcate our lives in so many ways. And so many brilliant writers have theorized borders. In that poem, “Borderwound,” I referenced an iconic old passage by Gloria Anzaldúa from her book Borderland/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. And there are also many living poets of the undocumented diaspora who are writing into this question, I think with far more precision than me. I want to give a shout out to the anthology I was lucky to be a part of, that was put out recently by Undocupoets called Here to Stay. I think that the entire anthology problematizes the idea of borders so richly. And in a way, my book answers that question in poems better than I can.

In my book, I turned to poems to unpack complexities like the idea of borders. More broadly, I'm interested in moving beyond dominant paradigms, like the ways that you mentioned that borders have marked our lives. I'm interested in questioning how that came to be and considering how we can get more free, how we can really honor the idea that we as people need each other beyond illusions of national belonging. And I think so much of the book is attempting to wrestle with that question.

PHIL

Beyond “Borderwound,” is there a poem in the book that you would point to for an exploration?

PATRYCJA

That's a good question. I mean, one thing that comes to mind, that isn't just a specific poem, is the way that rivers show up in the book, and how the image of the river is one way that that question continues its attempt to be answered in different poems. And the long poem, “On Belonging,” attempts to unpack that toward the end of the book. But throughout—I'm looking at my table of contents here to think about it—the poem “Wilno” also, which considers the place where my grandfather was born, near a city that's now Lithuania. And so there are a number of poems in the book that are thinking through that idea.

PHIL

There are many, many instances in the book of images of water filling all kinds of things—your body, your mind, your person in every way. Oftentimes, that's done in a way that's welcomed by the speaker of the poem and it's under the control of the speaker of the poem. But I'm curious about your relationship with nature, and how you think about the mingling between the self and nature, and whether you think people need to surrender more to nature.

PATRYCJA

My relationship to nature is one that I deeply believe in nourishing, and also I don't like to be prescriptive about how people should live. I think there are so many ways to live a life and to form our particular relationship to place. I do think it's worthwhile to contemplate and honor our relationship to the natural world, which is not some separate out there, to recognize our interdependence with ecosystems, with bodies of water which are foundational to all of life. Water in particular has been a source of contemplation and solace for me, but it's the kind of solace and comfort that doesn't deny grief. Since childhood, I think being in a relationship with non-human living things is crucial to me as a writer and a person. To visit a favorite tree, to laugh, watching squirrels chase one another up it. It's those deceivingly simple things that just feel inexhaustible. I also think that we have to remember fresh water is a finite resource, that there's a cost to forgetting that. It's often on my mind—our interdependence with the natural world and how much we can learn from the non-human living world.

PHIL

I want to switch gears slightly and talk thematically for a few questions. The book not only contemplates, but really confronts, the relationship between the present and the past, and between ourselves and our ancestors. I'm curious—what do you think we owe to our forebearers? Is there anything that they owe to us, or is it more that we just have to reflect on and be thankful for all that they've given us?

PATRYCJA

God, it's such a beautiful hefty question and one that I brought upon myself I guess by writing this book. I love that question. It feels so impossible. I think what we owe to the past, if anything, must be enacted in our present. In my case, I owe generations of hardworking people in my family my dedication to the work I'm here to do, and to figuring out what that work is. And I think for me, that work has to do with writing and making art and reading deeply and supporting other writers and artists and being in meaningful relationships with the people in my life and to the land. I suspect there are many people in my family line who never could listen to the fullness of their longing, who had to focus solely on putting bread on the table.

And so there's actually so much I don't know about the dreams of the people who came before, because they were working too hard to ever articulate their dreaming. There's no record of their dreaming. In that sense, I want to say I don't think they owe me that, but there's this part of me that is like, you owe me that I need to hear from you. I need to know what you dreamt of. And in a way, writing poetry, it's like I'm attempting to connect to what those longings were. There's a sonnet crown in the book, “Saint Hyacinth Basilica,” where in part I call forth my great-grandmother on my mother's side who I feel this improbable kinship with despite knowing so very little about her life, I’ve never even seen a photograph of her. I don't know if it's that we owe the past our imaginative engagement, but I believe in that and I like to think that the dead can feel us reaching toward them. And so this book is in part about that. It's about recognizing and honoring the uncharted in us and in our lineage, what we can't know about what came before. It's also for me about reaching intragenerationally to other living beings, as you mentioned, living children of immigrants, other people, when I can't reach back. I keep thinking about past, present, and future as being extremely entwined.

PHIL

You mentioned the longing of our ancestors, and one of the many beautiful sections that stood out to me in the book is from “Archival,” where you have the lines:

Migration is the story of longing

is the story. To risk

rupture for rapture.

And it's such a tight, contained little set of lines, but I think it really contains so much, and every time someone chooses or is forced to migrate, there's all kinds of risk of pain and displacement and dislocation. I'm curious whether you think the book provides an answer to the question of whether those journeys are worth taking for the possibility of that kind of rapture, or is that something that I don't even know?

PATRYCJA

It's a question that I almost would want to turn back to readers, the part about what people think the book says about that. Because gosh, for me, it's an endless and painful question. The life of a child of those who took that risk, my life threatens to answer that question. And I say threaten because I wonder if we want to know the full answer. What I mean is that I've felt the pressure of that question since childhood, whether the risk is worth taking with everything my parents sacrificed to immigrate here, unable to see family for so long. My writing, my life, is haunted by that. I don't know that I have an answer, particularly because empires crumble. The American dream continues to be revealed to be an illusion time and time again. There's so much that hasn't unfolded the way that maybe my parents dreamt, and yet their dream was bigger than nations. Risk is a life force. Longing and desire are a life force. So yes and no, maybe, is the answer of whether the risk is worth taking. As you point out, there's also so much pain in stories of migration. I would be really curious how readers perceive that because it's a question I'm still asking of my own life.

PHIL

Another thing I noticed and enjoyed about your poems is that the rhythm and the line breaks and the flow of so many of the poems has this organic feel to it, something that I think mirrors the idea of a river flowing. For example, in the section of the poem “Night” called “Pluck,” you have these lines:

Pollen untethers

one answer

from another

shattering into

Once upon a time

in an alley, city gave Night their quiet back

at what cost I do not ask.

And there's no punctuation break between “shattering into” and “once upon a time,” and there's just a comma in that whole section of lines. I'm curious whether you were consciously trying to have some of the forms of the poem reflect that kind of bleeding into and over that is present in the thematic elements of the book.

PATRYCJA

Yes, absolutely. I'm so interested in spillage and mess and crossover and fluidity and fragmentation. These are definitely intimately connected with the aforementioned questions of belonging, nation states, desire. All of that is so messy in my own mind. And I think human thought processes are so nonlinear that I love that poetry is capacious enough to allow for that kind of bleeding, as you mentioned, that kind of multiplicity of themes and questions that happen at the same time because we hold in our bodies so many questions and experiences at the same time. So yes, there is a desire in some of the poems in the book to get at that through form and punctuation itself. Of course, I feel like that's one of the gifts of poetry. I do think it's one of those things that poetry gets us to really think about—the line as its own world and what happens when you start putting all these worlds in conversation. And that series of night poems is an older one and came out of a time when all I could write seemed to be fragments too. So I honor that in the book as well, this time in which I could almost only write in fragments.

PHIL

There is this real, deep sense of kinship, emotion and devotion with the natural world as we were talking about. In “On Chronic Conditions,” there's this line “permeable to the world,” and yet at the same time there's so much embodiment and physical intimacy in the book. I'm curious how you think about that duality, that kind of merging with the natural world, but also being embodied, having a longing for a sensuous life. Obviously one can do both, but I'm just curious about how you think about that balance.

PATRYCJA

Yeah, it's thrilling. This thought of merging with the natural world or is that even possible, as you allude to in your question, as the body is its own border and there's this separation, and yet at the same time we are of the earth and arguably we'll be returned to it. I am fascinated by that. I think a lot of writers and artists help me contemplate that question. I think of the work of Ana Mendieta who has these performance pieces, stills from video footage and visual depictions of her own body with the landscape and times where she left her imprint on the land, and I feel like her work contemplates this question of our separation or not, of ways we might be able to merge or might not. I'm really interested in what you speak about here—are they opposite ends of the spectrum, this idea of our sensuous embodiment and the permeability and connection to the natural world?Are those actually two different things?

When I think about being present in my body and feeling my feet on the ground, there's something so connective about really feeling where my feet actually are when they touch the ground, and honing in on what's the temperature of my body and the temperature of the earth and all these things that when you get down to the nitty gritty of it can get us contemplating, how separate are we, really? I feel like in the book, the speaker at different moments feels more and less connected to the world around her, and that just mirrors how I feel on any given day.

PHIL

You mentioned earlier about turning a question back to readers about how they would feel. I understand you feel so completely invested in it, but when We Contain Landscapes becomes published and it's out in the world, it ceases to be just yours and it becomes partly or even mostly something that's experienced and held by your readership. You obviously can't control how people are going to respond to the work, but I'm curious, what feelings would you want to evoke in them? What feelings would you want them cycling through in the days and weeks after they encounter these poems?

PATRYCJA

That's so lovely. I think, for one, I want people to be invited into, lovingly and maybe slightly disturbed into thinking about their own desires and longings, and taking those seriously. I'm invested in all of us being more curious about our thoughts and our interiority, and slowing down enough to go there. I think in the world as it is right now—in service of putting profit above all else—it is really difficult to live a life in which we are afforded the possibility of accessing those uncharted parts of ourselves, of learning more about what it is we desire, of tapping into our dreams, unpacking what dreams were passed down to us, what is ours, all of that. I wish for people to feel permission, for even a moment, to go there in as an emotionally safe way as possible, while also being maybe pushed,too, to go somewhere a little bit uncomfortable, to feel able to be in touch with grief, and to know that they're not alone in their grief.

There's the famous James Baldwin quote about this very thing, about how—oh, I'm going to misquote it—but the ways in which we think our individual aches are so particular and unprecedented and we've endured the most pain. Then books connect us to this history of pain and remind us we're not alone. It's much more precisely put by Baldwin.

But I think this idea of “you are not alone” and also “what is your particular longing?” is an invitation into a deeper feeling that I want the book to give permission to. I would love to hear back from readers about what it opened up for them. I let this book be messy in some ways in terms of its many reachings, to try to hold space for many types of feeling.

PHIL

“On Belonging” is this long poem at the end of the book, and there's a line that really stuck with me, which is:

Family constructs in us

the sacred and the profane. Forming a covenant.

As we talked about, we are the literal embodiment of our ancestors, and it's crazy that we're even here, but that brings with it all the things that we were talking about—the burdens of the past and messiness and pain. We might try to escape it, but we can't. I'm just curious about two things: One, what the idea of that covenant means to you; and two, based on a question in “On Belonging” that really has stuck with me, which is, “Can you belong to what you've lost?”

PATRYCJA

To the first part of your question…there are these religious undertones to the word covenant that are just so rich for me. As I mentioned earlier, I think particularly as a Polish American writer, I'm always thinking about the inherited, my inherited faith tradition having been raised Catholic. When I think about family, that is so linked to questions of faith for me, and then this idea of covenant as agreement, it just gets me thinking about what contracts we have with both our blood family and the families we make, and what it is, if anything, that we must break in those, what it is that is unbreakable. Those are things I'm often contemplating. One idea that really encapsulates that for me, that's also a big thread in the book that sort of goes unanswered but ever explored, is the idea of devotion and thinking about inheriting a familial and religious idea of what devotion means, and then starting to unpack what devotion is. This feels connected to the question of the agreements we make with each other, of our family ties and all of the messiness of that.

As for what we've lost, whether you can belong to what you've lost, it's a question in the book because I don't have an answer. But I do think the losses we've endured somehow take up space in us, and that's so interesting to me.

There are eternal poetic questions, ideas like negative capability. I think so many artists are compelled by the question of loss and nothingness, and these kinds of abstract ideas, but loss is also very concrete in our lives. We can feel the presence of a missing person or thing, even an object when it's gone—we see the spot on the windowsill where it used to sit. It's really fascinating to me to contemplate how loss can construct our identity, and that, of course, connects to larger questions of people maybe losing a homeland, in some cases never being able to go back. I think of living and gone Palestinian writers and how they write about the homeland and that immense loss. So I think it's not a question that I actually have an answer to, and that long poem on belonging attempts to question what ideas we inherit about belonging itself, and how if we buy into too narrow of an idea of belonging, we're not considering these other people and places that we might belong to, including maybe that which is gone.

PHIL

I'm very curious if you can talk me through the process that you went through to get the book published. I know originally it also had a different title, and so I'm curious if you can talk about that too.

PATRYCJA

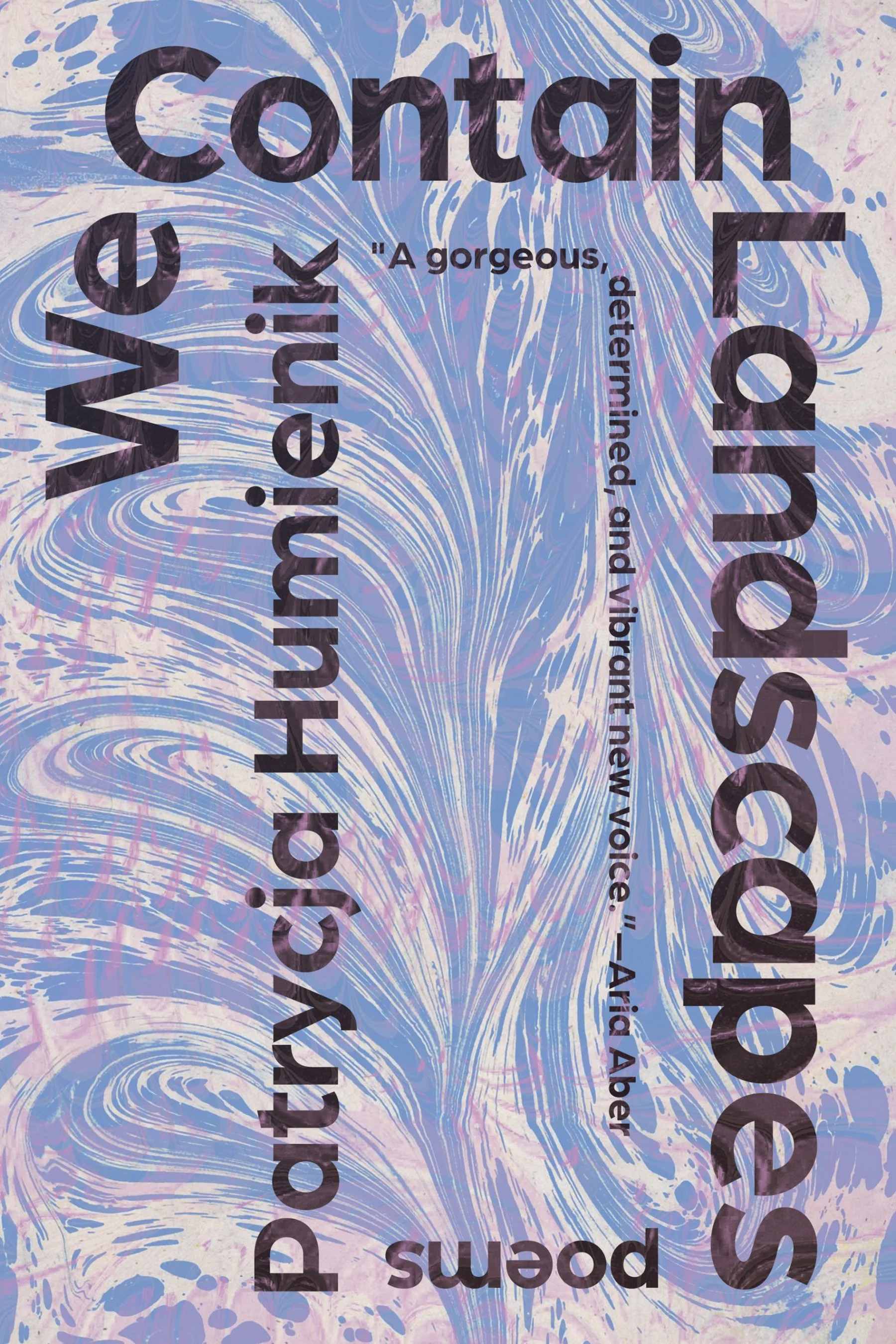

So there's a poem in the book called “Anchor Baby” toward the end of the book, and that used to be the book's title. It was a really fruitful title that helped me write so much of the book. I think titles can be propulsive in that way. I was submitting the book to various contests and open reading periods under that name. Prior to that, or alongside the process, some of that book came out of a chapbook called We Contain Landscapes that I never submitted anywhere, but I realized it was all in conversation together. Meanwhile, under the Anchor Baby title, my book got picked up blessedly by Tin House. After some time and conversations with my editor and the Tin House team, as I continued working on the book, it became clear that We Contain Landscapes was the true title that allowed for a wider range of questioning already happening in the book.

I think that the kind of project that Anchor Baby may have been would have involved perhaps a more rigorous and overt examination of immigration in particular, which was not what the book was doing. We Contain Landscapes ended up feeling like the truest title for it, but that didn't come for some time. The process of returning to that title felt true to the book because I'm so obsessed with spirals in the book, and it was a sort of spiraling back I often think about an image of the spiral staircase in the book itself, and about the ways that in our lives we can walk up and down a sort of spiral staircase of our obsessions and questions, and look at them from different vantage points. And so it was like I suddenly looked at that title from a different vantage, and even though I was scared of it—I still am intimidated by claiming a “we,” —I was like, okay, I'm ready to invite this layer onto the book, even if it brings questioning or suspicion. I welcome all of that. I welcome a suspicion of what the “we” is and means. And so I finally felt ready to return to that title that I was intimidated to claim earlier on.

PHIL

Last question—what kind of things are you working on now in your writing?

PATRYCJA

Well, I'm slowly working toward a second book of poems that I don't have too much to say about yet because I'm just letting the new work reveal itself to me. I'm also very, very slowly working on a novella project. The way that my writing tends to work is I uncover a lot through the process of drafting. I'm drafting to uncover what these next books are.

Patrycja Humienik, daughter of Polish immigrants, is the author of We Contain Landscapes (Tin House, 2025). An editor and teaching artist, she has developed writing and movement workshops for the Henry Art Gallery, Arts+Literature Laboratory, The Seventh Wave, Northwest Film Forum, and in prisons. Her work can be found in The New Yorker, Gulf Coast, Poetry Northwest, Poetry Daily, Poetry Society of America, the Slowdown show, and elsewhere..

Phil Goldstein is a poet who has worked professionally as a technology and business journalist, a content marketer, editor, and marketing copywriter. His debut poetry collection, How to Bury a Boy at Sea, was published by Stillhouse Press in April 2022. His poetry has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and a Best of the Net award, and his work has appeared in Atlanta Review, South Dakota Review, HAD,The Shore, West Trade Review, Atticus Review, South Florida Poetry Journal, Jet Fuel Review, The Laurel Review, and elsewhere. By day, he works as an editor and copywriter for a large technology company. He currently lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife and their animals: a dog named Brenna, and two cats, Grady and Princess.